Long-term finance is vital to driving Africa’s economic growth and development. Africa currently faces significant long-term finance gaps in the real and social sectors. FSD Africa estimates that the funding gap for SMEs, infrastructure, housing and agribusiness is over USD 300bn per year that is currently not being met.

Significant strides have been made during the past decade to enhance financial inclusion across Africa. These improvements in the outreach of financial markets were made possible due to the rapid uptake of digital financial services. The use of new delivery modes, such as agent banking and mobile phones, to send and receive payments has completely reformed the financial sector’s outreach to remote, previously excluded users. While still more at the experimental stage, digital platforms increasingly enable the provision of financial services relating to savings, credit and insurance.

However, although inclusion of a large segment of the population as senders and recipients of dal payments certainly serves to empower a previously marginalized segment of the population, it does little to promulgate the core function of financial markets. The purpose of financial intermediation is to enhance the economy’s productive potential by facilitating more optimal allocation of scarce resources. Channeling capital to the most needed uses will contribute to meeting investors risk/return objectives while also augmenting the growth potential of African economies.

When compared to the ‘inclusion revolution’ of the last 10-20 years, progress in enhancing access to investment finance resulting in greater productive employment has been disappointing. Increasing the availability of long-term finance will support investments in the housing, infrastructure and enterprise sectors thereby, directly creating job opportunities. In addition, such investment in social and real sector projects will enhance productivity, and thereby contribute to poverty alleviation through potential sustained increases iosable incomes.

One of the key challenges faced by investors has been the lack of good quality information and information asymmetry on long-term finance. Enhancing domestic capacity in the provision of long-term finance is crucial to filling the sizeable long-term financing gaps that apply almost universally to the African infrastructure, housing and enterprise sectors. Only by harnessing the contribution of long-term finance made available by the private sector will African countries effectively leverage the limited resources made available by the public sector and by donors. Often, African policymakers are confronted with challenges in balancing large and invariably well-justified expenditure demands with very limited fiscal resources, and as a result governments resort to domestic security issuance to fund their current expenditures.

As investors find it more attractive to put their money in ‘risk-free’ government-issued securities, increased issuance of such securities reduces the willingness of loinvestors (banks and institutional investors) to take part in funding risky productive investments. In order to stem this ‘crowding out’ of risk-capital by the government, a concerted effort is required to strengthen management of fiscal resources; to better utilize existing sources of long-term funding, as provided by banks and institutional investors; as well as to develop new sources of domestic funding. Over time capital market financing may come to play a larger role in filling the financing gap that exists in developing economies, provided the approach adopted is appropriately tailored to the development challenges faced by small, underdeveloped markets.

In conclusion, the objective of promoting sustainable economic growth and job creation through greater provision of long-term finance is crucial for Africa and its people. It is imperative that decision-makers, both policymakers, investors, development finance institutions as well as development partners embrace measures that will enhance productivvestment in support of Africa’s economic development.

The Long-Term Finance Initiative

We have collaborated with the German Development Cooperation (GIZ), African Development Bank (AfDB) and the Centre for Affordable Housing Finance (CAHF) to support the Long-Term Finance Initiative, which has two main interventions:

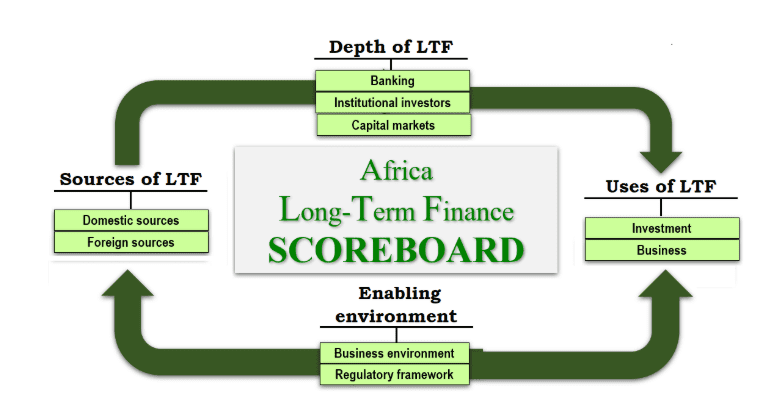

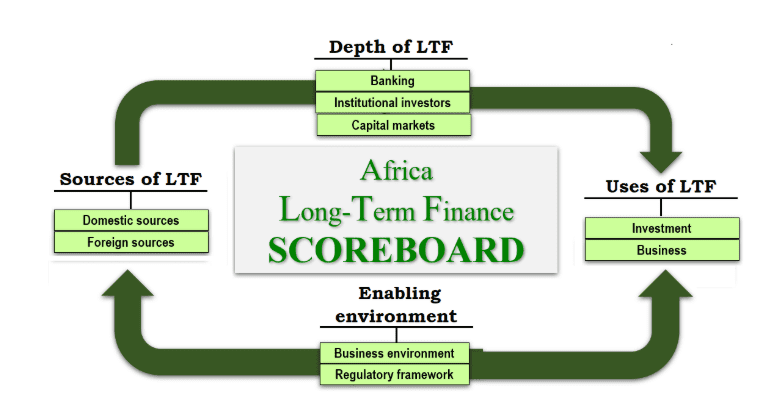

- The Long-Term Finance Scoreboard:

The purpose of the Scoreboard is to assemble information about the sources and uses of long-term finance in Africa – whether provided by governments, donors, foreign direct investors or the domestic private sector. Previously, information and data on the availability of long-term finance in Africa has been scarce, spread across numerous sources, or simply unavailable. Thus, the intention of the long-term finance initiative is both to bring together existing sources of information as assembled by third parties and to augment the availability of data as regards long-term finance through collection of primary data. The Scoreboard also provides bench-marking that will facilitate comparison of how countries are performing vis-à-vis one another, thereby engendering interest and applying peer pressure among countryakeholders.

The purpose of the Scoreboard is to provide information to policy makers, private investors – both domestic and foreign investors – and development partners to support their decision-making as regards investments in Africa. The pilot website currently under development will be published in the coming months with a view to soliciting feedback and enhancing the scope and quality information provided.

Link to the live and online scoreboard: http://afr-ltf.com

- In-country diagnostics:

The purpose of in-country diagnostics is to identify effective ways to deepen local markets for long-term finance. By mobilizing local, private sources of finance and more effectively leveraging funding provided by the public sector, African economies will gradually be able to reduce reliance on donor funding and foreign direct investment. The diagnostic framework is based on a comprehensive approach to long-term finance that ranges from contributions of governments, donors, and private sector funding, whether provided by local or foreign investors, to funding intermediated by banks and capital markets, and other sources of private finance, such as private equity or venture capital.

The intention is that country diagnostics will inform country reform programs and create momentum for dialogue among key public and private sector stakeholders, thereby enhancing the focus and effectiveness of implementation efforts.,