Pillar: Adaptation and Resilience

Key points

- These efforts have led to large-scale and long-term change, providing access to financial services to over 10.2 million people and addressing issues related to financial exclusion.

FSD Africa, a UK aid-funded specialist development agency, today celebrated a decade of strengthening financial markets across Africa, growing economies, increasing incomes for vulnerable populations, and combatting poverty.

FSD Africa has made significant strides over the past decade by advancing policy and regulatory reforms, enhancing financial infrastructure, and increasing capacity, all while tackling systemic issues in Africa’s financial markets.

These efforts have led to large-scale and long-term change, providing access to financial services to over 10.2 million people and addressing issues related to financial exclusion. During the Covid-19 pandemic, FSD Africa observed a remarkable 87% increase in the demand for and use of remittance services, which played a crucial role in protecting families from the pandemic’s financial impacts.

FSD Africa’s market-building initiatives have resulted directly or indirectly in £1.9 billion of long-term capital made available for SMEs, affordable housing, and sustainable energy projects, among others. Its support for financial sector innovation has increased access to financial services for close to 12 million Africans, while its support for business growth has improved access to finance for more than 3 million African businesses and led directly or indirectly to the creation of over 35,000 new jobs.

Speaking during the event, Mark Napier, CEO at FSD Africa said: “Celebrating over ten years of our trailblazing work across Africa is special: in a short space of time, we have strengthened and developed financial markets and tapped into capital by using new instruments such as green and gender bonds. The future is key, and I look forward to continuing our hard work with our collaborative and innovative team. I have no doubt that we will continue to support and address Africa’s expanding needs as we move towards sustainable economic development.’’

Future-focused, FSD Africa’s strategy has evolved to address Africa’s expanding needs, with a greater emphasis on identifying innovative methods to mobilize resources for sustainable economic development. The organization has recently boosted its investment into projects that enable an equitable transition to a green future for Africa after several successful initiatives, including developing regulations and assisting green bond issuance programs in Kenya and Nigeria. The organization’s green portfolio and pipeline have expanded because of continuous investments in programs that provide environmental and social consequences, with close to £50 million being invested in green initiatives.

Jane Marriott, OBE, British High Commissioner to Kenya said: ‘”The UK is continually working with Kenya to promote green finance and economic growth as part of the UK-Kenya Strategic Partnership. FSD Africa is delivering on these priorities in Kenya and across the continent, creating over 35,000 jobs and leveraging more than KES 300 billion into sectors like renewable energy. I look forward to FSD Africa’s continued work in the years ahead.”

Prof. Njuguna Ndung’u, Cabinet Secretary, Kenya National Treasury said: ‘’Kenya’s partnership with FSD Africa has created a favorable environment for the growth of our local capital markets, resulting in increased interest from both domestic and foreign investors. FSD Africa also played a crucial role in establishing the Nairobi International Financial Centre (NIFC), positioning Kenya to receive more financial flows. We look forward to collaborating more closely with FSD Africa on green finance initiatives to promote sustainable development while addressing climate change challenges.’’

Read original article

Africa is endowed with abundant and diverse natural resources and natural capital wealth. Close to 8% of the Earth’s natural gas reserves, a third of global mineral reserves, and a 10th of the global oil reserves reside in Africa. Also, over two-thirds of the world’s arable land and a third of the world’s CO2-storing tropical rainforests are domiciled in Africa. Africa’s mineral wealth makes it potentially one of the richest continents, yet Africa is home to the poorest countries in the world.

Despite having historically low emissions levels compared with other regions, Africa’s CO2 emissions are fast growing due to increased emissions from its tropical lands. This recent growth is driven by increased natural resource extraction and consumption linked to increasing material use on the continent and abroad in recent decades.

As indicated in Sustainable Development Goals 8.4.11 & 12.2.12, it is important for Africa to focus on sustainable exploitation management and consumption of natural resources. But while the literature is replete with studies on the material footprints of nations and the world at large, there is a lack of studies focused on tracing the trends and understanding the determinants of Africa’s raw material extraction and footprint.

Africa’s extraction and export of raw materials is rising

The findings of a new study that calculates sub-Saharan Africa’s raw material footprint over the past two decades, shows that production and consumption levels nearly doubled between 1995 and 2015. Africa is a net exporter of raw material footprints across all material categories – biomass, construction materials, fossil fuels, and ores. Raw material equivalents of exports referred to as raw material footprints embodied in Africa’s exports of goods and services to the rest of world increased by 53%, from 1.95 gigatonnes in 1995 to 2.98 gigtonnes in 2015.

The raw material footprint in African exports increased for almost all African countries. Countries such as South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, Algeria, Angola, and Ethiopia saw the highest growth in raw material equivalents of exports over the period. Meanwhile, the biomass footprint in African exports increased by 43% over the same period, reflecting Africa’s increasing agricultural commodities exports, such as cocoa, palm oil, coffee, tea, and cotton, among other cash crops, and horticultural products, particularly to Europe and Asia.

The fossil fuel footprint in African exports was highest in South Africa, Algeria, and Nigeria, while Western Africa (Mauritania, Guinea, and Ghana) and Central Africa (Democratic Republic of Congo) made up more than a third of the ore footprint.

These soaring levels of raw material equivalent of exports reveal the strong connection between raw material extraction and growth strategies of African countries. Is this rewarding and sustainable?

The cutting down of major carbon sinks and digging up of mineral resources for export and the associated detrimental impact on the environment and climate change has not resulted in resilient growth, economic transformation and prosperity on the continent.

There has been a lack of structural transformation whilst informal employment has increased over the years. A study due to be published in 2023 shows that informal workers in Africa are mostly at the lower tier segment of the labour market, a dead-end with little chance of moving up the job ladder.

There are bigger questions as to how African countries can create opportunities to allow these low-tier informal workers to move up the job ladder. Can African countries create better jobs opportunities using their natural resources?

The distressing correlation between debt and raw material footprints

The findings of this study reveal a strong and positive correlation between national debt and raw material footprints embodied in African exports.

This is distressing. Given the sky-rocketing debt levels of many African countries, exploitation of natural resources is one of the key avenues available to combat their debt crisis, although it comes with a heavy environmental cost.

With the current growth and development paradigm, raw material equivalents for exports are set to increase substantially in a bid to service their debts using mineral and oil revenues, but this has disastrous consequences for the environment.

As much of the world focuses on the next steps in addressing the climate crisis, the funding squeeze and rising debt levels means that climate action will take a back seat in African countries. Increasing debt and intensification of extraction of raw material for export will leave Africans in extreme poverty.

This finding shows the urgent need to bring the debt issues upfront when discussing climate change, and the call on lenders to see their role in Africa’s growing environmental burden.

Policy options

The current Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report indicates the need to urgently hold global warming to relatively safe levels but in doing this would require global cooperation such as working with African government in this area.

In the short term, it is important for lenders both multilateral and bilateral, and international community to accelerate debt restructuring and with all seriousness and urgency provide the needed support to put countries back on a more sustainable fiscal path. The distressing debt levels mean there is very little fiscal space to invest in health, education and on climate to support the population.

The ongoing debt restructuring negotiations must take into account these intersections with the environment and climate change as well as the mutual benefits. With support from the international community, it is important to put together a more agile and effective sovereign debt resolution framework that can provide African countries with the needed financing assurances and debt relief in a timely manner.

In the long term, African countries must rethink their growth and development paradigms and focus on creating wealth via adding value to these vast raw materials. With all the natural resources and the discovery of new rare earth elements (cobalt, lithium, nickel, tantalum, tungsten etc.) essential for facilitating the green energy transition, African governments must focus on how they can be more involved in the value chain across all material category, especially in the manufacturing sector.

Given the large reserves of many critical minerals on the continent, particularly in South and East Africa, Africa should work towards positioning itself as the global supplier of critical minerals and a hub (mining and production) for rare earth element acquisition in the world.

This would involve pulling together a new approach and policies that would ensure mutually beneficial mining investment on the continent aimed at wealth creation, particularly investing in the networks and value chains and harnessing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to boost productivity and investments.

Also, as has been done by the Dangote group in the building of the oil refinery in Nigeria, African governments should create the enabling environment and necessary support such as providing public incentives for private projects to attract private finance to develop the networks and value chains in the sector.

Read original article

These trees are Gabon’s superstars. They absorb and store millions of tons of earth-warming carbon dioxide each year, a critical function for the global fight against climate change. They also fuel the country’s timber industry, a major focus of economic development during the past decade.

In today’s financial markets, Gabon’s trees are worth more dead than alive. Despite the billions pledged worldwide to fight climate change, little has been distributed as compensation for the global benefit that trees provide. In 2021, Gabon received its first payment for reducing forest-related emissions—$17 million via the Central African Forest Initiative.

The timber industry, on the other hand, contributes about $1 billion to Gabon’s annual gross domestic product. It could be a great deal more. Unlike some of its neighbors, the country strictly limits logging, palm oil production and other activities that lead to forest destruction; it’s suffered less than 1% forest loss since 1990, compared with about 14% for continental Africa.

Now that oil production, the country’s primary source of revenue, is dwindling, leaders are reevaluating the money-making potential of the forests. Opening more land to timber companies is one option, but for now Gabon’s environmentally minded government is more interested in keeping the trees alive—if the international financial markets can make it worthwhile.

The best avenue for that, Gabon says, is the $2 billion-and-growing market for “carbon offsets.” That’s traditionally been limited to those who can document improvement on past environmental practices, not those who, like Gabon, never wrecked their forests in the first place. That’s because for a carbon offset to fulfill its function of compensating for its buyer’s emissions, it needs to have financed something that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. But in Gabon, forest protection has been happening anyway.

Still, Gabon insists it should be compensated for the air-purifying service its trees provide. Otherwise, it hints, its commitment to forest preservation may take a backseat to more traditional economic development. In its recent national action plan under the Paris Agreement, the global climate pact, the country says it plans to remain a “net-carbon absorber”—if it gets access to international finance through a carbon market.

“There is no financial instrument to support Gabon to continue to offer this critical ecosystem service,” Akim Daouda, the chief executive officer of Gabon’s $1.9 billion sovereign wealth fund, said in an interview during a recent trip to London. “Can we monetize the forest and keep it for the rest of the planet? Or do we need to find a way to respond to the needs of our population?”

Gabon’s per capita GDP is the highest on the continent, but there’s little evidence of wealth past or present in Nyanga. One of the few local health centers lacks running water, exposed wires poke out of the walls, and bare mattresses cover four, cast-iron bedframes.

The province is home to a 100,000 hectare (247,000 acre) cattle ranch, part of the Grande Mayumba project. A flagship of Gabon’s “sustainable development” efforts and backed by investments from the family offices of the Westons, Fricks and Sarikhanis, Grande Mayumba’s plans include logging, cattle farming and eco-tourism, as well as an area 37 times the size of Manhattan set aside for conservation.

The ranch raises N’Dama, a small chestnut-colored breed of indigenous beef cattle that tolerate tsetse flies and the sleeping sickness they carry. The 4,000-strong herd will grow and eventually roam alongside wild buffalo and antelope. The free-range model will minimize harm to the savannah ecosystem, and careful grasslands management could boost the soil’s carbon stock, according to Africa Conservation Development Corp., Grande Mayumba’s parent company.

The ranch isn’t profitable yet. So far, only Grande Mayumba’s logging operation is fully operational. The rest has moved far more slowly. To raise the money needed to really get the project off the ground, ACDG will need to issue and sell carbon credits.

The forest-based carbon offsets on the market today tend to be based on projects that seek to avoid emissions or increase carbon storage. Limiting deforestation usually qualifies; so could planting trees. Developers usually calculate how the forests fared under their control compared with a historical baseline, then sell the difference in units of extra tons of carbon removed or avoided as offsets.

But because Gabon already has stringent restrictions on logging and there’s little deforestation to speak of, ACDG has had to take a different approach. Based on trends in more than a dozen once-highly forested countries, it contends there’s an imminent threat to the trees in Nyanga. Pending government approval, ACDG will sell credits based on how Grande Mayumba’s activities avert that hypothetical future destruction.

“There will be development in the Grande Mayumba area over time,” said Rob Morley, science and environmental planning director at ACDG. “This will either be unsustainable, unplanned and that will lead to a large amount of forest loss, or it will be planned.”

On the ground, the threat feels distant. About the size of Israel, the province is Gabon’s poorest, with just three paved roads, two hospitals and few public services. Residents have gone looking for better opportunities in Gabon’s main cities, leaving a population of around 53,000.

The Grande Mayumba project says it will generate as many as 4,000 jobs, mirroring President Ali Bongo’s Gabon Émergent, the country’s three-pillar development strategy based on industry, the environment and a services economy. Most will work in forestry or ranching, but a handful will staff a luxury ecolodge under construction in neighboring Ogooué-Maritime province. For $2,000 per night or so, well-heeled tourists will be able to see hippos frolic in the surf and ghost crabs dash in and out of the waves.

When ACDG figures out how to stabilize a runway on the sandy soils, guests will be able to access the lodge by plane. Until then, it’s a half-day journey from the nearest main town, by car, river barge and speedboat. The last leg is by quadbike along a strip of beach frequented by buffalo and the odd elephant, tide permitting.

In its original plans, Grande Mayumba expected its model to generate as many as 200 million credits over the next 25 years. At today’s prices, that would be worth about $2 billion, according to data provider Allied Offsets, roughly equal to Gabon’s sovereign wealth fund.

So far that’s yet to materialize. The British bank Standard Chartered Plc and Swiss trading firm Vitol SA have expressed interest, but neither have culminated in a deal. Investors are getting antsy.

Josh Ponte, a former gorilla researcher and special adviser to the President of Gabon and now an ACDG director, bemoaned the delay in carbon-credit revenue.

“The carbon play was a core incentive,” he said, sitting on a rudimentary platform that will eventually be a dining room. Other than some staff lodging, there’s little more to see. “But there’s since been a reality check on the timeline of the carbon credits, how they’ll work, and how they’ll fit with government strategy. It’s really tiring our investors.”

Gabon Vert, the environmental pillar of the Bongo administration’s development plan, frames both its deal with ACDG and the country’s plans to issue its own, sovereign carbon offsets. Gabon’s offering will rely on different math. It plans to tally the CO2 its trees suck out of the atmosphere, subtract its own emissions, and sell the difference to other, more polluting countries as “net sequestration” credits.

Anyone can issue carbon credits, and anyone can buy them. Most developers use third-party verification bodies to vouch for the quality of their offerings. Gabon doesn’t plan to do so. Fledgling exchanges are also trying to streamline trade, but for now, over-the-counter, bilateral deals are the most common.

It’s not clear the markets will bite. Gabon’s plans have been met with caution. It’s yet to sell some 90 million credits it already generated for past carbon absorption using an established albeit contested approach.

“It always makes me nervous when people say they’re going to roll out their own methodology,” said Danny Cullenward, policy director at nonprofit research group CarbonPlan. “It’s really easy to manipulate the methodology intentionally or incidentally to produce outcomes that are less credible or inconsistent with other key points of data.”

Methodology aside, political uncertainty hangs over Gabon. The fate of Gabon Vert may depend on the outcome of the presidential election later this year.

Though a member of the Bongo family has led Gabon for the past 56 years, the current presidency is under a cloud. Ali Bongo won his most recent election by fewer than 10,000 votes, triggering charges of ballot-rigging and days of violent protest. A 2019 coup attempt failed, and Bongo has had a stroke.

Ahead of this year’s presidential election, the government has embarked on an aggressive green diplomacy push. In February, a delegation joined the UK’s environment ministry and King Charles III to chat conservation. This week, Emmanuel Macron will attend a “One Forest” summit in Libreville, the first time a French president has visited the country in about a decade.

The Grande Mayumba project was already halted once, in 2015, when Gabon’s then-oil minister gave the site of a proposed port to a Moroccan company, despite an agreement that assigned it to ACDG. Development stalled until the dispute was resolved in 2018.

“If the president were to change, I’m not convinced that the model has got deep enough roots yet to be fully sustainable,” said Lee White, environment minister in Bongo’s government. The project also is facing a groundswell of opposition from local communities and NGOs. A grassroots campaign called “No to Grande Mayumba” calls for the suspension of the plan, saying restrictions on access to resources threaten the custom and livelihoods of subsistence farmers who haven’t been adequately consulted.

“There’s sacred forest here and the local population should be consulted on what can and can’t be cut down,” said Nicole Nouhando, governor of Nyanga province who’s broadly supportive of ACDG’s plans.

ACDG has had its own turmoil. Alan Bernstein, the South African safari entrepreneur who founded the company, left after a falling-out with its biggest investors. ACDG says he no longer holds stock in the group; Bernstein says he is seeking compensation after an initial court settlement in January.

For now, Gabon and ACDG are pushing ahead. In the absence of oversight, their success depends less on whether the credits help avert climate change and more on whether and how much a buyer will pay.

In December, US oil company Hess Corp. sealed the first purchase agreement for a similar kind of “high forest, low deforestation” credits with Guyana. Earlier in the year, the International Civil Aviation Organization said those credits could be used by airlines to offset their emissions. Experts have cautioned the credits will fail to serve their purpose.

If ACDG or Gabon can make a deal, it will add fuel to the efforts of other rainforest nations across the world’s tropical belt.

It could also pit the government at odds with the private sector. Gabon is one of a handful of countries with agreements to generate and trade their own carbon credits under a new carbon market run by the United Nations, according to Trove Research Ltd., a carbon analytics company. Last year, White castigated TotalEnergies over a new forest-based credits plan in Gabon. “They don’t have the rights” to that carbon, he said.

ACDG retains the government’s support. The success of the Grande Mayumba project would encourage “forest countries to continue preserving their forests,” said Daouda of Gabon’s sovereign wealth fund, which will market the country’s carbon credits. For him, it would answer the country’s big question in the affirmative: “It would mean that today, the world is recognizing that a living tree has higher value than a dead one.” —With Akshat Rathi and Ben Elgin

Read original article

As countries around the world race to combat the effects of climate change, carbon trading continues to gain traction.

Carbon trading is the buying and selling of permits of carbon credits that allow the holder to emit a certain amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (GHGs).

Financial site Investopedia defines a carbon credit as the equivalent of one tonne of carbon dioxide or any other GHGs that an organisation can emit into the atmosphere.

Essentially, companies are awarded credits to allow them to continue to pollute up to a certain limit, often on a reducing basis.

What happens when a company exceeds its limits?

While some businesses are able to cut their emissions, others are not able to do so. For some, their emissions might even increase in the course of a given period.

Those that cannot reduce their emissions are, however, allowed to continue operating, but usually at a higher cost.

In some instances, businesses are unable to exhaust their credit limits even after operating for the marked duration. These are called ‘‘surplus’’ or ‘‘excess’’ credits.

When a business is left with unutilised credits, it can sell them to other businesses. The business may also choose to keep the surplus credits for future use.

What is the difference between carbon credits and carbon offsets?

While carbon credits and carbon offsets are sometimes used interchangeably, they are different commodities with the same goal of reducing the emission of carbon and other GHGs into the atmosphere.

Carbon credits are limited to within an area and are regulated by a governing body. It is this governing body that is also responsible for creating and distributing them to companies operating within that jurisdiction.

Carbon offsets are neither created by a specific entity nor distributed by a particular body. Instead, they are traded freely on ‘‘voluntary markets.’’

Read: Northern Kenya conservancies eye pie of carbon credit billions

While carbon credits ‘‘cap’’ emissions, carbon offsets compensate an organisation for investing in carbon projects, also called green projects, that help to cut down emissions.

Carbon offset projects can be realised through activities that either reduce the emission of greenhouse gases or those that increase carbon sequestration.

Some of these activities may involve investment in renewable energy forms to displace fossil fuels that emit carbon and reforestation to increase the number of trees that serve as carbon sinks.

Does Kenya have a history of carbon trading?

This trade dates back to 2014. A group of 60,000 smallholder farmers in the Western region under the Kenya Agricultural Carbon Project (KACP) earned carbon credits for sustainable farming.

The credits had been issued worldwide under the sustainable agricultural land management (SALM) carbon accounting methodology.

The programme supported the farmers to grow crops in a productive, sustainable and climate-friendly manner.

With its forests, expansive grasslands and wetlands, Kenya is considered a rich carbon offset sink. This is expected to improve even further once the country attains its target of planting 15 billion trees in the next 10 years.

How is carbon trading regulated in Kenya?

One of the functions of the National Climate Change Action Plan under the Climate Change Act of 2016 is ‘‘to guide the country toward the achievement of low-carbon climate-resilient sustainable development.’’

It does not, however, address specifically how trading in carbon credits, as a climate change response, will be regulated in Kenya.

Environment lawyer Stella Ojango acknowledges the gaps, noting that Kenya’s limited regulatory framework and absence of requisite laws make carbon trading in the country an almost opaque undertaking.

‘‘We have the Climate Change Act of 2016, but it does not address carbon trading sufficiently. We need to amend that Act so that we can introduce regulations for trading carbon. Enriching our laws will help to regularise this business.’’ Ojango says.

Last year, the Nairobi International Finance Centre (NIFC) said Kenya lacks a clear framework for buying and selling carbon credits locally.

The body noted that this unregulated sale of carbon credits costs the country billions of shillings in unrealised revenues.

The organisation is planning to establish a carbon trading exchange in the country to allow small-scale trade-in credits.

‘‘We need to have in place mechanisms that measure how much carbon is being absorbed through reforestation. This way, we will have created a market. Regulating the pricing aspect will then become easier,’’ Ojango adds.

How are carbon markets regulated elsewhere?

Kenya is not alone in lacking proper regulation for carbon trading. Most of the carbon credit markets in the developing world are unregulated by law. There are no agreed prices for carbon credits.

Plans are underway to establish a global carbon credit and carbon offset trading market. This was agreed on by negotiators at COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. Carbon credits also exist within markets with Cap & Trade regulations.

Who is trading in carbon credits in Kenya?

A number of businesses and organisations are already making money from either carbon credits or carbon offset programmes.

In Northern Kenya, conservancies are increasingly moving away from tourism as their mainstay to now invest in carbon projects as a source of revenue.

Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT), for instance, has put 4.7 million acres of grassland under a carbon project.

NRT is a group of 39 marine and land conservancies that cover, among other counties, Laikipia, Samburu, Tana River and Lamu. Out of these, 14 are under the project.

The Northern Rangelands Carbon Project will focus exclusively on the removal of carbon from the soil, with a target of 50 million tonnes of CO2 in 30 years. This effectively makes it one of the few projects of this scale in the market globally.

Last year, Kenya Forest Service (KFS) signed a deal with global audit firm BDO that would see the government agency earn millions of shillings for offsetting carbon dioxide.

According to the deal, KFS will rake in $15 (Sh1868) for every tonne of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere by government forests.

In villages in coastal Kenya, communities living near the sea are selling ‘‘hewa kaa’’ to international corporations to help them reduce their carbon emissions.

This carbon project is promoting the conservation and sustainable use of mangrove resources by the villagers.

Controversy of trade

While widely adopted around the world today, carbon credits still divide opinion. Those in support say carbon trading is a ‘‘measurable and verifiable’’ emissions reduction strategy through climate projects.

Those opposed to carbon offsets call the trade ‘‘a scammer’s dream scheme’’ and the next big thing in greenwashing.

Climate change advocacy organisation Greenpeace dismisses carbon offsets as a bookkeeping trick ‘‘intended to obscure climate-wrecking emissions.’’

Read original article

Final beta version to follow on heels of agreement on Target 15 in new Global Biodiversity Framework.

Following the adoption of the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) at Montreal’s COP15, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) said the release of its V0.4 beta framework in March would further assist firms in assessing and reporting on biodiversity and nature-related risks.

Speaking at the TNFD’s ‘Moving to Action After Montreal’ webinar, David Craig, Co-chair of the TNFD, called the GBF an “ambitious framework” and highlighted its role in “halt[ing] the degradation of nature and biodiversity”. He also underlined the importance of the GBF in ensuring “harmony in nature” by addressing restoring natural ecosystems, which the TNFD’s disclosure framework aims to support.

The GBF featured 23 targets and four goals, but Target 15 is viewed as vital to private-sector management of biodiversity-related risks.

Also speaking on the webinar, Emily McKensie, Technical Director at the TNFD, said there were “key points of conceptual alignment” between the finalised GBF – including Target 15 – and the TNFD framework.

Harmony in nature

Target 15 requires governments to encourage companies and financial institutions disclose their risks, dependencies and impacts on biodiversity along their operations, supply and value chains, and portfolios.

“Target 15 means that disclosures on nature impacts, dependencies and risk are coming and we’re seeing more and more activity to support these,” said Craig. “The TNFD is a framework and a tool to support Target 15.”

McKensie underlined the momentum the TNFD could offer the GBF and Target 15, through its focus on helping firms and investors to disclose and risk manage nature-related impacts and dependencies.

She also highlighted the TNFD framework’s ability to help “operationalise” which organisations will regularly monitor, assess and disclose nature risks, dependencies and impacts, resulting in a “clear connection” to Target 15.

However, the GBF was accused of being “watered down” by a number of observers due the word ‘mandatory’ being excluded from the framework.

Maelle Pelisson, Advocacy Director at Business for Nature, who was privy to the behind-the-scenes negotiations at COP15, admitted that mandatory disclosures would have helped in “levelling the playing field” and demonstrating urgency.

Speaking on the webinar, Pelisson told onlookers the GBF would still help businesses to access data required to accelerate action on reducing negative impacts on nature. Pelisson also welcomed the engagement of businesses at COP15, as well as the rapid growth in momentum surrounding biodiversity and nature.

“We’ve seen this momentum growing so fast from March to December last year,” she said. “We can only expect that it will continue growing now that [the GBF] been adopted.”

September launch and beyond

According to Craig, disclosures are important because they “demonstrate accountability”, but he stressed that they are “meaningless” unless companies take action.

“What’s really important is that companies have invested the time the talent, the knowledge and the skills,” he said. “Don’t underestimate the urgency of the crisis, but also the urgency of the movement,” he added. “The GBF agreement is ambitious [but] it’s real targets will be set by governments and businesses who will see growing pressure and action to align on these targets.”

The TNFD framework builds on the four core pillars of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) for corporates and investors, and is expected to be incorporated into the disclosure standards of existing sustainability standards bodies and national laws.

Alexis Gazzo, Europe West Sustainability Co-leader at EY, told attendees on the webinar that implementation of TNFD guidance will be much faster than TCFD due to the framework “building on the foundations that have been set up for climate”.

The TNFD will run a formal consultation where market participants can submit responses to a full draft of the beta framework from March until 1 June. The pilot testing of the framework, which has been running since 1 July 2022, will also finish on the same day.

The final beta framework is expected to provide additional guidance on disclosure metrics, measurement of impacts, dependencies and risks across supply chains, and the sector-specific reporting requirements, including agriculture, aquaculture and mining.

TNFD’s framework will then be finalised in September 2023.

The next UN Biodiversity Conference (COP16) is scheduled to take place in Turkey in 2024. It will likely see countries providing updates and reviews of their national biodiversity plans targets. Countries will also be expected to develop their national financial plans as a part of their resource mobilisation for implementation.

Read original article

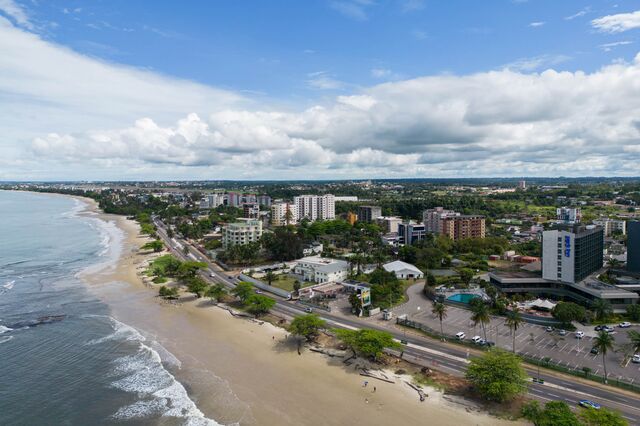

Renewable energy projects attracted investments worth $382 billion globally in 2021, according to the International Energy Agency, but only $13 billion, or three percent of that, funded projects in Africa, highlighting a major funding gap foiling green transition and energy access on the continent.

With only 48 percent of African population having access to electricity, experts say investment in the continent’s renewable energy sector could both leapfrog the green transition efforts and connect more people to the grid.

Despite this, it has been established that investors with the capacity to invest in this sector shy away from the African market, a problem which brought together several stakeholders in the energy sector in Nairobi this week, attempting to change the narrative.

At a forum convened by the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, participants drawn from the private sector, government, civil society organisations from Kenya and beyond deliberated on how investors can be mobilised to support Africa’s green transition through investments.

Reluctant to invest

Rebekah Shirley, WRI’s deputy regional director told the forum that private sector players are reluctant to invest in this sector, creating a funding gap of billions of dollars every year, despite the wide access gap.

“Even in other regions of the world where energy access is still a challenge like the Southeast Asia, we don’t see funding gaps of this magnitude, why Africa?” she posed.

Alex Wachira, principal secretary for the state department of energy, said that there is a list of challenges contributing to the energy gap, even in Kenya, which slow down economic growth in the country.

“We (the Ministry of Energy) are aware of the many challenges attributed to this, including limited incentives to attract private sector investors,” he said in a speech read by a representative.

Lack of political will

Another challenge identified is the lack of political will for appropriate legislation and implementation of policies to incentivise private sector investment in renewable energy projects, especially in rural areas.

For instance, only two of Kenya’s 47 counties have drafted energy plans that would give way to appropriate energy policies, deprioritising renewable energy projects at the local governments.

This, according to Eva Sawe – a senior programmes officer at the Council of Governors, is because lawmakers have not been sensitised on why renewable energy projects should be a priority.

But even with the right policies and incentives to support private sector investment in renewable energy on the continent, investors said there is a still a shortage of talent in Africa limiting the production capacity of companies investing in the sector.

“If an investor is coming into the country to do any renewable energy project, the first hurdle they will face is the lack of skilled people,” said Andrew Amadi, the chief executive of Kenya Renewable Energy Association.

Read original article

From sunshine to rare minerals to a youthful population, Africa has the raw ingredients to make the green transition. Now it needs the finance.

Take power. Exceptionally strong sun and vast swathes of desert mean Africa is the region with the highest solar generation potential over the long term, according to calculations by the World Bank. It’s now cheaper to build and operate new large-scale wind and solar farms in many parts of the world than to keep running coal or gas-fired power plants. With more than half of people in Sub-Saharan Africa living without electricity, expanding solar should be a no-brainer.

Yet investment in renewable energy in Africa fell to an 11-year low in 2021, comprising just 0.6% of the global total, according to a report by BloombergNEF. Financing options are insufficient and expensive because lenders worry about the risks of taking on new projects in often politically or economically unstable countries with broken supply chains — though the opportunities can be unrivaled.

“African cities and economies are growing faster than anywhere in the world, so it’s ripe for transformation. The question is why we are not seeing the uptick in investment we should expect,” said Wanjira Mathai, regional director for Africa at the World Resources Institute. “The biggest challenge right now is the cost of capital. To unlock that would be absolutely catalytic.”

Renewable Investment in Africa

Source: BloombergNEF

Note: Global renewable energy asset investment by region

The world’s least developed continent, Africa produces just 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions but is already suffering some of the worst consequences of a changing climate. Rich nations have never met a 2009 pledge to funnel $100 billion a year to help developing countries shift toward cleaner energy sources and bolster their infrastructure against extreme weather.

At the UN-sponsored COP27 climate talks in Egypt last year, delegates agreed to create a new fund for countries battered by climate disasters, though the details have yet to be hammered out. And private sector lenders are calling for multilateral development banks to play a bigger role in financing clean energy projects in poorer nations.

It’s an issue that looms large over this year’s climate conference, which is taking place in Dubai.

Africa needs investments worth $2.3 trillion to meet the needs of its population, plus an additional $1 trillion to bolster its infrastructure against climate disasters, according to estimates from the Africa Finance Corp.

Even the continent’s buzzing startup scene lags behind the rest of the world. Africa was on the receiving end of just over 1% of the $415 billion in venture capital that went into the startup sector globally in 2022, according to research firm Briter Bridges. Of that, 15%, or around $800 million went into “clean tech” or “climate tech.”

Faced with limited resources and immediate challenges, governments are making stark — and divergent — choices.

“Two days ago, we went to distribute food relief to 4.3 million affected Kenyans in an emergency program that has forced us to re-allocate funds budgeted for education and health,” Kenya’s newly-elected president, William Ruto, told COP27 leaders in November. “The tradeoffs we are forced to make between indispensable public goods is evidence that climate change is directly threatening our people’s life, health and future.”

Ruto called for Africa to leapfrog fossil fuels and embrace clean power as the foundation of its future development. Lacking the oil, gas and coal deposits abundant in some parts of the continent, Kenya has embraced renewables instead. Over 90% of its power comes from sources including solar, wind and geothermal. It also beat the European Union by four years in banning single-use plastic bags and is now considering forcing drivers to pay a congestion charge to curb pollution, a measure that only London has enacted and that New York is debating.

“They ban coal, and we follow, they say firewood is not for fetching, they say we need to plant more trees,” Bola Tinubu, a leading candidate in this month’s Nigerian presidential elections, said in October. “If you don’t guarantee our finances and work with us to stop this, we are not going to comply with your climate change.”

The Just Energy Transition Partnerships are an effort to respond. The first was signed in 2021 between South Africa and the US, the UK, the European Union, Germany and France. The $8.5 billion financing package was designed to help South Africa transition away from coal and provide a blueprint for new agreements between developed countries and middle-income nations that depend on dirtier fossil fuels.

The details of the deal weren’t agreed until a few months ago though, with South Africa and its partners disagreeing about how the money should be spent. In the meantime, South Africans have faced daily power rationing as the loss-making state utility Eskom struggles to manage its ageing coal-fired plants.

The African Hydrogen Partnership, a grouping of private sector organizations, is pushing to develop green hydrogen as an alternative fro everything from public transport to clean cooking fuel.

“Our focus is on the domestic market,” said its co-founder and vice-chairman Siegfried Huegemann. “It’s where we see great potential, fantastic potential for developing new industries.”

When pipelines and harbors are built, however, Africa could become a major source of green hydrogen for markets elsewhere. The continent has the potential to produce €1 trillion ($1.1 trillion) worth of green hydrogen annually by 2035, according to a study by the European Investment Bank. As with electricity generation, however, transformational changes of that magnitude need money.

“We know that the climate challenge will be significantly difficult to manage and to adapt to — and in Africa the opportunity is dependent upon building resilience and economic resilience above all,” Mathai said. “You can see what a vicious circle this is.”

Read original article

-

Human activity is destroying biodiversity faster than ever before.

-

Almost 80% of threatened species are impacted by economic activity.

-

The COP15 summit has started work towards a new global pact on nature protection.

-

5 key transformations can save the natural world and boost GDP by trillions of dollars.

Whether you live in a city, a rural area or by the ocean, it’s likely you have noticed a decline in biodiversity. Maybe fewer birds visit your urban feeders, larger mammals are less common in the fields and forests around you, or your catches on those fishing trips are getting smaller.

What we’re all witnessing is a potentially catastrophic loss of biodiversity on which entire ecosystems depend.

Global efforts to protect nature

In an ongoing effort to slow the destruction of nature, delegates at the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal, Canada, focused on reversing the rapid decline of animals, plants and insects. The conference, also known as COP15, worked towards a new global agreement to protect biodiversity.

In a strongly worded opening address, UN Secretary-General António Guterres told delegates that “humanity has become a weapon of mass extinction”. Guterres piled further pressure on attendees by describing the conference as “our chance to stop this orgy of destruction”.

The destruction to which Gueterres refers spans the globe and is happening on a massive scale. According to a UN Global Land Outlook assessment, more than 1 million species are now threatened with extinction, vanishing at a rate not seen in 10 million years. As much as 40% of Earth’s land surfaces are considered degraded.

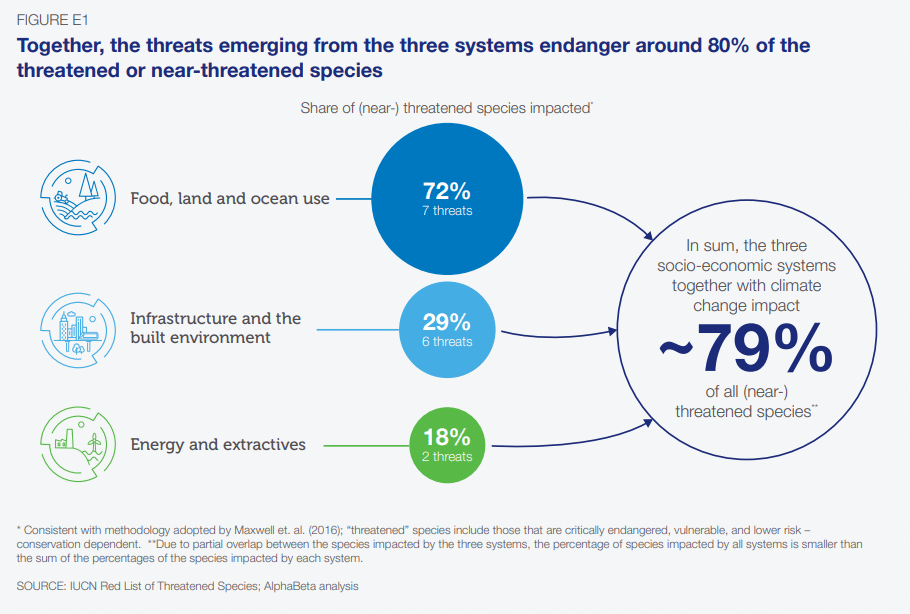

Research by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature found that human activity for food production, infrastructure, energy and mining accounts for 79% of the impact on threatened species.

Human systems for food, infrastructure and energy are destroying biodiversity. Image: WEF/IUCN

Creating a nature-positive economy

Only by fundamentally transforming these systems can we shift from destructive human activity to a nature-positive economy. The World Economic Forum’s New Nature Economy Report II sets out a range of transitions that will reverse nature loss and pull us back from the brink. Without these changes, the world will suffer irreversible destruction of biodiversity that will have far-reaching impacts on the economy and all life on Earth.

The report delivers a stark warning about the risks we are creating by destroying nature, stating that “$44 trillion of economic value generation – over half the world’s total GDP – is potentially at risk as a result of the dependence of business on nature and its services”.

Biodiversity loss was ranked as the third most severe threat humanity will face in the next 10 years in the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2022.

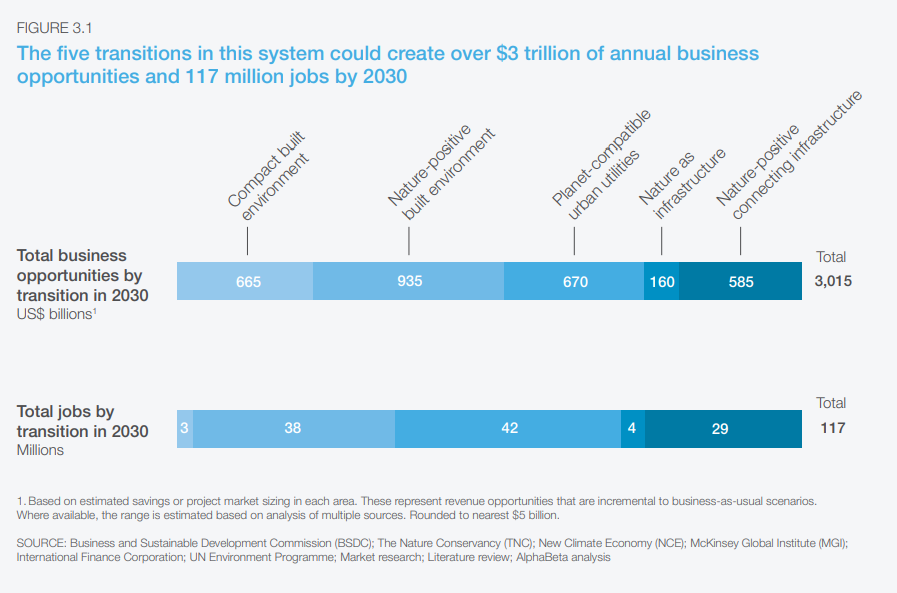

Five key transitions in the global economy could have a dramatic impact in slowing the loss of biodiversity, while bringing trillions of dollars of new economic opportunities and creating more than 100 million jobs.

Five key transitions in the global economy could have a dramatic impact in slowing the loss of biodiversity. Image: WEF New Nature Economy Report II

These transitions are:

1. Compact built environment

Higher-density urban development will free up land for agriculture and nature. It can also reduce urban sprawl, which destroys wildlife habitats and flora and fauna. Existing cities and settlements should be considered for strategic densification. Conservation-management projects should be established to protect biodiversity in areas that have been spared from development. This transition creates a $665 billion opportunity, with 3 million jobs created by 2030.

2. Nature-positive built environment

These built environments share space with nature. They are less human-centric, instead placing biodiversity at the core of project design. Infrastructure is located to avoid or minimize the destruction of nature, and all buildings are energy and resource efficient. Developments must include nature-friendly spaces and eco-bridges to connect habitats for urban wildlife. There’s a $935 billion opportunity in these built environments, and the possibility to create 38 million jobs by 2030.

3. Planet-compatible urban utilities

To stall biodiversity loss, we need utilities that effectively manage air, water and solid waste pollution in urban environments. In addition to benefiting nature, this will provide universal human access to clean air and water. Smart sensors and other Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies can transform urban utilities and make them planet-compatible. Creating them could deliver a $670 billion business opportunity and create 42 million jobs by 2030.

4. Nature as infrastructure

This transformation involves incorporating natural ecosystems into built-up areas. Instead of developments destroying floodplains, wetlands and forests, they would form an essential part of new built environments. This approach to development can also help deliver clean air, natural water purification and reduce the risk from extreme climate events. The business opportunity by using nature as infrastructure could hit $160 billion and create 4 million jobs by 2030.

5. Nature-positive connecting infrastructure

“Connecting infrastructure” includes roads, railways, pipelines and ports. Transitions in this area mean a change in the approach to planning to reduce biodiversity impacts, with a willingness to accept compromises when it comes to travel time and distance between departure point and destination. Building in wildlife corridors and switching to renewable energy in transport are key elements of nature-positive connecting infrastructure. The business opportunity here could peak at $585 billion, with the opportunity to create 29 million new jobs by 2030.

Time to make peace with nature

The outcomes of the COP15 biodiversity summit will shape the direction of humankind’s relationship with the natural world.

Costa Rica, once home to rampant logging, has now almost doubled the size of its rainforest. They turned it all around within a generation. It can be done.

Protect people and the planet. #COP15 #ActOnClimate #biodiversity #deforestation #rewilding #solutions pic.twitter.com/zKtBd1NlTs

— Mike Hudema (@MikeHudema) December 19, 2022

António Guterres urged delegates to overcome their differences and reach agreement on protecting nature, telling the conference: “it’s time for the world to adopt a far-reaching biodiversity framework – a true peace pact with nature – and deliver a green, healthy future for all.”

Read original article

Thousands of delegates gathered for the 2022 United Nations biodiversity conference (Cop15) in Montreal in December, tasked with finding a pathway to halt the alarming decline in global biodiversity. The negotiations eventually produced a landmark agreement to protect 30% of the Earth’s land and oceans by 2030, along with a host of other targets to reduce the loss of biodiversity.

While the agreement was signed by national governments, private sector representatives were conspicuous by their presence at the conference. But financial institutions have increasingly been making commitments to protect and enhance biodiversity in recent years, giving rise to a plethora of new jargon.

“Nature-based investing” – where investors provide benefits to nature and ecosystems, alongside achieving a financial return – is the latest buzzword. At the heart of this approach is the acknowledgement that “natural capital” – in other words, the Earth’s biodiversity and natural resources – provides benefits, often defined as “ecosystem services”, to the human population.

Nature is clearly indispensable to many economic activities. In Kenya, for example, tourism is making rapid progress in recovering to pre-pandemic levels, when it generated over 8% of GDP, and the tourist trade depends heavily on the lure of the country’s wildlife. Threats to biodiversity and ecosystems in Africa and around the world are therefore an issue of profound importance for investors, as well as governments.

“We have been losing natural capital at such an incredible rate over the last 60 or so years, and the pressure from consumption and demographics is so huge, we are now at that point in time where there’s just not enough resources to go around,” warns Alejandro Litovsky, CEO of consulting firm Earth Security. “There’s a real question around the operating conditions for companies and assets that depend on the services that have been free for a very long time.”

The sixth extinction?

The gravity of the crisis facing nature has sometimes been overshadowed by the climate crisis (which is itself one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss). But the data on nature makes for grim reading. Over 6,400 species of animals and 3,100 species of plants in Africa are at risk of extinction, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Globally, the scale of the disaster is such that many scientists argue that the Earth is entering its sixth period of mass extinction. This puts the current biodiversity crisis on a par with the asteroid strike that wiped out the dinosaurs 65m years ago.

The destruction of vital ecosystems across many parts of the world is the consequence of prevailing economic models prioritising short-term gain at the expense of long-term sustainability. “I spend a lot of time with African leaders,” says Kaddu Sebunya, CEO of the African Wildlife Foundation, “and they’ll tell you frankly that ‘the global economy doesn’t pay or reward me if I secure forests. But they reward me if I cut down the forest and export sugar.’”

But when habitats are lost or damaged, it is often humans who pay the ultimate price. The devastating mudslides that hit Freetown, Sierra Leone, in August 2017, killing over 1,000 people, were partly caused by deforestation on hillsides around the city. As the city grew, its surrounding hills lost much of the tree cover that had held soils together and provided a natural drainage mechanism.

Other African cities can benefit from following Freetown’s example, says Pool. “Nature-based solutions, when implemented and deployed properly, can be really useful in improving air quality, in reducing extreme urban heat, improving the quality and the supply of water, in reducing the risk of landslides and flooding, and so on.”

Financing dilemmas

The 2022 UN biodiversity conference produced a historic agreement on biodiversity – but the conference concluded in controversial circumstances. In declaring the text of the agreement to be final, the Chinese president of the conference ignored the objection of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which was continuing to seek additional financial commitments from wealthy nations.

“We didn’t sign the agreement,” Ève Bazaiba, the DRC’s environment minister, said. “It is not possible for us to implement it. We cannot accept the level of ambition without more finance.”

The UN Environment Programme states that the private sector currently provides only 17% of total investments into nature-based solutions. It estimates that total financing will need to more than double, to $384bn a year by 2025, in order to meet biodiversity goals.

The fact that financial institutions are lining up to express their enthusiasm for nature-based investing may be seen as an encouraging sign. Gautier Quéru, head of the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund, which provides long-term financing to projects that meet strict environmental and social standard, says Cop15 has brought “momentum” to nature-based investing.

“Public money will not be enough to meet the objectives,” he says. “We need the mobilisation of private sector actors, including finance and industry. And the good news is that at Cop15, the positive mobilisation of the business and finance sector was really striking.”

A natural fit?

While the availability of finance is one part of the challenge, investors also need to determine what, in practice, they can actually invest in when it comes to nature.

Devang Vussonji, a partner at consulting firm Dalberg, says that the difficulty of measuring and assigning value to different types of biodiversity is a major factor holding back investment in nature-based solutions in Africa.

“There’s a lot the market needs to figure out,” he says. “What do we value and not value?

“How do we set a price around it? How do you compare mangrove populations declining to elephant populations declining? How do you compare tropical areas to temperate areas and so forth?”

For many investors, a possible starting point is carbon credit schemes, which are designed to conserve or enhance forests that act as carbon sinks – theoretically enabling companies to offset emissions from other activities. Such schemes are mainly intended to contribute towards net zero targets, but nature is a possible added beneficiary.

“There’s now a recognition that if the carbon markets have proven themselves, are beginning to take off, there’s good demand for products as well as good supply of products, then the same can be replicated for broader nature-based investing as well,” says Vussonji. “The first of those opportunities we’re seeing is piggybacking on carbon credits, so as carbon credits are being created or being sold, other ‘biodiversity credits’ can be added on to them.”

While private sector finance has an indispensable role in conserving biodiversity in Africa and elsewhere, another essential element is coordination between the public and private sectors.

Sebunya emphasises that governments and NGOs must help provide a pipeline of projects that investors can adopt. Even where funds may be available from impact-focused investors, he says, “finding the bankable pipelines that are shovel-ready for investors is a huge, huge challenge”.

The African Wildlife Foundation, in an effort to meet this challenge, has been working with the Rwandan government on ways to support the mountain gorilla population in the country’s Volcanoes National Park. With the gorilla population expanding thanks to the success of recent conservation efforts, Sebunya says that thoughts are turning on how to expand their habitat.

One solution, he suggests, is encouraging local communities to grow bamboo – the gorillas’ favourite food – as a cash crop. This would potentially provide a win-win solution, allowing locals to generate income from selling bamboo to companies that could process the crop into various products, while providing a food source for the gorillas.

Will life find a way?

Conservation will have to compete with many other priorities in Africa, including the need to ensure a food supply for a human population that is set to almost double by 2050. “You do have that trade-off between protecting virgin nature and cultivating food for a growing population,” Litovsky acknowledges. Developing agricultural techniques that regenerate natural ecosystems will be “really quite fundamental” to Africa’s future, he adds.

Yet it is worth bearing in mind that Africa has in fact been more successful than most of the world in retaining its biodiversity up to now. The continent hosts around one-quarter of the Earth’s biodiversity. It contains the mighty Congo Rainforest, one of the “green lungs” of the planet. Its megafauna have remained relatively intact, thousands of years after early humans slaughtered the largest animals they encountered on other continents.

“Africa today has abundant nature in many places and abundant natural resources,” says Litovsky. “If you think about those as an asset that can be monetised in a variety of different ways, as part of a long-term economic development model, then that can really create a very exciting prospect for how Africa can develop into the future.”

Read original article