The ocean is a vital part of human life and the global economy, providing food, jobs, and livelihoods for over 3 billion people. However, climate change, overfishing, and pollution are threatening the ocean and the prosperity of people in developing countries. Coral reefs, mangrove forests, and marine populations have already suffered, with a third of global fish stocks depleted. If these trends continue, no stocks may be left for commercial fishing in the Asia-Pacific region by 2048. By 2052, the weight of plastic in the ocean could surpass that of fish, and up to 90% of coral reefs may be lost. Despite these challenges, the ocean remains the planet’s largest natural asset, delivering countless benefits to humanity.

- The ocean is responsible for the oxygen in every other breath we take. It supplies 15% of humanity’s protein needs.

- It helps to slow climate change by absorbing 30% of carbon dioxide emissions and 90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases.

- It serves as the highway for some 90% of internationally traded goods, via the shipping sector.

- If the ocean were a country, at several trillion dollars per year of economic activity, the ocean would rank 7th on the list of largest nations by GDP.

- It is the source of hundreds of millions of jobs, in fisheries, aquaculture, shipping, tourism, energy production and other sectors.

Protecting the ocean from the many threats it faces is not only a moral imperative but also a promising financial opportunity. By responsibly managing the ocean, we can benefit both the environment and the economies of emerging markets. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the ocean economy was on track to double between 2010 and 2030, reaching $3 trillion and employing 40 million people. The financial sector is starting to recognise the potential of a healthy ocean. It has a key role in shifting the global economic system towards rebuilding ocean prosperity, restoring biodiversity, and regenerating ocean health.

A thriving Blue Economy supports the sustainable use of coastal and marine resources, promoting economic growth, better livelihoods, and more jobs while preserving the integrity and health of these ecosystems. However, keeping the world’s oceans clean will require ambitious projects supported by innovative financing.

It’s upon this basis that FSDA and BFA Global partnered to launch TECA in April 2022; a first-of-its-kind venture launcher, to create fintech start-ups with solutions that enable climate resilience in the most vulnerable communities around the world, with an initial focus on Africa. The first wave, “The Blue Wave”, was set out to address challenges affecting the Blue Economy. It is expected that future waves will take on other challenges on climate change. The team kicked off activities by building a community of diverse, and engaged experts and enthusiasts to collaboratively ideate, strategise, and connect to provide feedback, and support a network for prospective founders as they launch their ventures.

BFA built an active online community interested in TECA and the Blue Economy in Africa on Circle, which onboarded 221 members who are active on the platform to date. The Wave Expedition Series; a series of online webinars in which the TECA Community learnt about and discussed opportunity areas and contributed to building the wave’s ‘Atlas of Opportunity’, ran from May to July 2022 with a total of six expeditions.

Sourcing for the first cohort of entrepreneurs was completed in August 2022, with selection based on talent, passion and commitment to building innovative solutions for a climate-resilient future. 30 fellows/entrepreneurs were onboarded in the inaugural wave with 50% being female, and representing 7 African countries: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Egypt, South Africa and Zimbabwe. The fellows kicked off with a huddle in Diani on the Kenyan coast in September 2022, with the huddle objectives being team bonding and trust building, testing hypothesis, exposure to the blue economy and working towards goals as a team (brainstorming together and building together).

Related article: 4 Innovation Opportunities to Unlock the Potential of Blue Carbon

Over a 4-month period, the fellows were taken through a mentorship and coaching program, including a “How I Launched” series to refine their venture ideas, after which they did one mock pitch, then a final pitch before a panel. The venture ideas were scored based on a 5-criteria matrix: compelling vision, team-solution fit, scalability/viability, impact on communities in blue spaces, and impact on blue ecosystems. 7 ventures demonstrated that they had refined their problem-solution fit and were working towards a minimum viable product (MVP), and thus qualified for an initial grant of £55,000. TECA will continue to build a diverse and engaged community through the Circle platform and publication of knowledge products. They will also work toward securing further funding for a second wave in FY23-24.

Here are some of the initiatives that have been implemented by the communities in Kwale county as discovered in the expedition:

Mikoko Pamoja Mangrove Restoration

Nestled between sandy beaches, still waters and coconut palms, the Mikoko Pamoja project — Swahili for “mangroves together” — has for nearly a decade quietly plodded away, conserving over 264 acres of mangroves while simultaneously planting new seedlings. About 4,000 new mangroves are planted yearly, steadily swelling Gazi Bay’s forests. The project is an integrated people-centred approach, with a particular focus on women, to address the triple crisis – poverty, climate change, and nature – at the local level.

Restoring mangroves is beyond conventional forestry. Besides developing nurseries and supplying seedlings, there is a lot more that must be considered in mangrove restoration, according to Swabra Mohammed; the secretary of Gazi Women Group. Her group established a nursery in 2018 and have sold seedlings for restoration. To the fellows, the huddle was an eye-opener. Over and above species zonation and assessing hydrology, they gained knowledge on identifying mature propagules of various species. The huddle was holistic and practical as it enabled the fellows to identify the challenges and opportunities in mangrove ecosystem restoration and blue carbon monetisation. With deliberate conservation, comes natural perks. Fisherfolk casting nets in nearby shallow waters have seen an abundance of species return to the mangrove-laden shores, now a breeding ground for fish flourishing in the expanded habitat. And project leaders hail the benefits of cleaner air for people who live in or near the forests.

Kibuyuni Seaweed Farming

It is estimated that Kenya earns around $2.5 billion annually from its ocean resources, a positive indication that there can be a potential growth of the country’s GDP through the embrace of Blue Economy. At Kibuyuni village in Kwale County, a group of 50 members is already making fortunes from seaweed farming. This project has improved the livelihoods of many families in the area.

According to Fatuma Mohamed, who chairs the Kibuyuni Seaweed Farmers Group, the project began in 2010 after KMFRI, conducted research that identified a seaweed species suitable for the area. The group, which at that time had 27 members, received funding from PACT Kenya in 2011 to improve their project. They currently cultivate two seaweed species, with a harvest cycle of 30-45 days, and sell around 50 tonnes, generating sales of approximately KES 1.5 million. The group invests their earnings in table banking and merry-go-round initiatives.

We are just beginning to explore how innovation can help us build climate resilience. It’s essential that more people get involved in supporting the development of solutions that can meet the challenges we face now and in the future, and ensure that we use our natural resources in a sustainable way.

The 2nd TECA blue economy wave will launch soon in partnership with BFA, IUCN and Ocean Hub Africa and aims to attract 50 fellows and launch 10 new ventures across sub-Saharan Africa. This was announced in the ocean conference, where the 7 grantees from wave 1 had an opportunity to learn more about the blue economy and pitch to potential funders.FSD Africa is committed to playing its part in bringing together the right people and resources to create a world that is better prepared for the effects of climate change. By serving as a catalyst and bringing people together, FSD Africa can help create a more climate-resilient world.

Photo credits: BFA Global

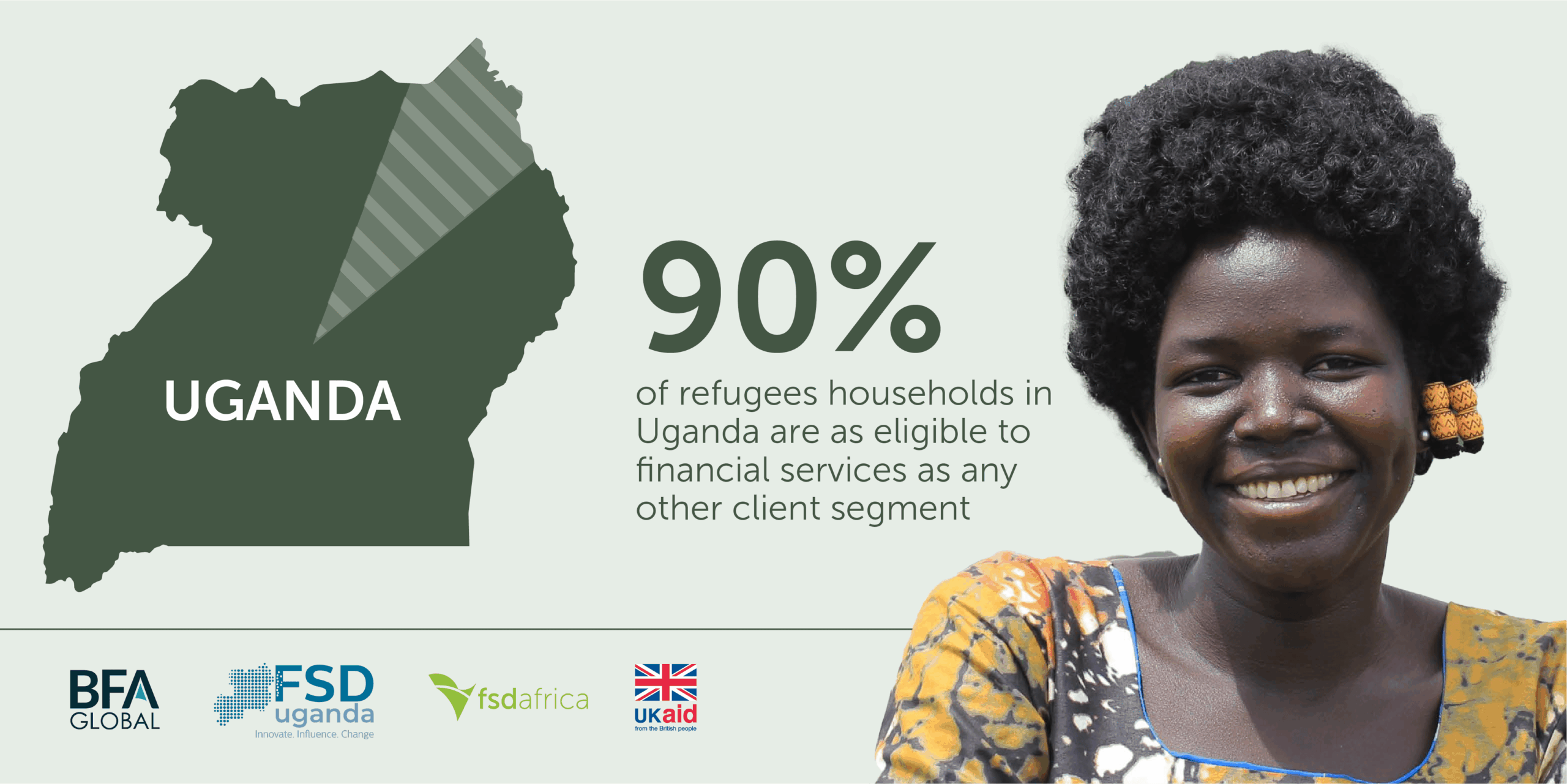

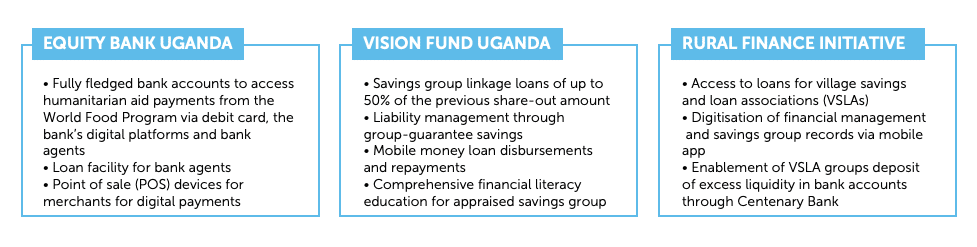

Amani fled conflict and persecution in his home country in South Sudan, and found solace in Uganda’s Bidi Bidi refugee settlement. Amani’s life took a transformative turn courtesy of the Financial Inclusion for Refugees (FI4R) Project supported by FSD Africa and FSD Uganda in partnership with local financial service providers.

Amani fled conflict and persecution in his home country in South Sudan, and found solace in Uganda’s Bidi Bidi refugee settlement. Amani’s life took a transformative turn courtesy of the Financial Inclusion for Refugees (FI4R) Project supported by FSD Africa and FSD Uganda in partnership with local financial service providers. Amani opened a savings account with Equity Bank, which enabled him to save money and start planning for a better future securely. With access to credit and affordable loans, Amani seized the opportunity to start a small business, selling handmade crafts within the settlement.

Amani opened a savings account with Equity Bank, which enabled him to save money and start planning for a better future securely. With access to credit and affordable loans, Amani seized the opportunity to start a small business, selling handmade crafts within the settlement. Through Amani’s dedication and hard work, his business flourished. Amani not only improved his own living conditions but also extended support to other refugees in the settlement with the income generated. Amani became an inspiration, encouraging fellow refugees to explore entrepreneurship as a means to financial independence.

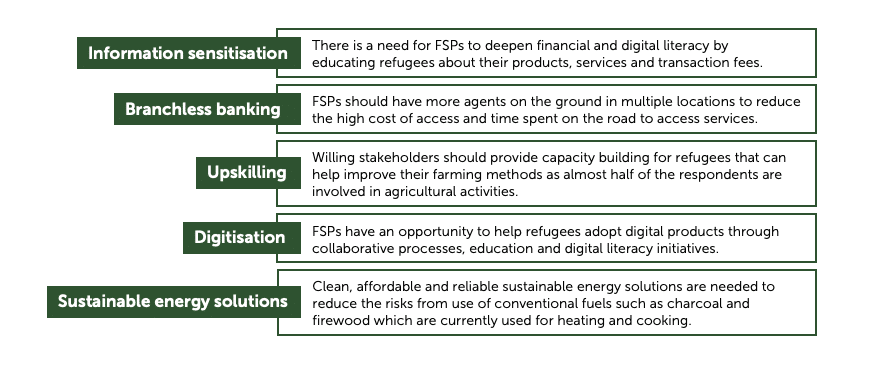

Through Amani’s dedication and hard work, his business flourished. Amani not only improved his own living conditions but also extended support to other refugees in the settlement with the income generated. Amani became an inspiration, encouraging fellow refugees to explore entrepreneurship as a means to financial independence. Recognising the importance of financial literacy, Amani actively participated in financial education programs organised by project partners. Amani learned valuable skills such as budgeting, saving, and managing cash flow. Motivated by his own success, Amani began mentoring other refugees, sharing knowledge and empowering them to take control of their financial lives.

Recognising the importance of financial literacy, Amani actively participated in financial education programs organised by project partners. Amani learned valuable skills such as budgeting, saving, and managing cash flow. Motivated by his own success, Amani began mentoring other refugees, sharing knowledge and empowering them to take control of their financial lives. Amani’s journey was not without obstacles. Like many other refugees, he faced uncertainties, limited resources, and occasional setbacks especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, through perseverance and the support of the refugee community, Amani remained steadfast in his pursuit of a better future. Amani’s resilience and determination served as a beacon of hope for others facing similar challenges.

Amani’s journey was not without obstacles. Like many other refugees, he faced uncertainties, limited resources, and occasional setbacks especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, through perseverance and the support of the refugee community, Amani remained steadfast in his pursuit of a better future. Amani’s resilience and determination served as a beacon of hope for others facing similar challenges. Amani dreams of expanding his business beyond the settlement’s boundaries, creating opportunities for fellow refugees and contributing to the local economy. Amani’s journey exemplifies the transformative power of financial inclusion and the impact it can have on the lives of refugees.

Amani dreams of expanding his business beyond the settlement’s boundaries, creating opportunities for fellow refugees and contributing to the local economy. Amani’s journey exemplifies the transformative power of financial inclusion and the impact it can have on the lives of refugees. Through access to financial services, coupled with resilience and community support, Amani has not only thrived but has become a source of inspiration for others. Amani’s story highlights the importance of creating an inclusive world where refugees are given a chance to rebuild their lives, contribute to their communities, and dreams of a brighter future.

Through access to financial services, coupled with resilience and community support, Amani has not only thrived but has become a source of inspiration for others. Amani’s story highlights the importance of creating an inclusive world where refugees are given a chance to rebuild their lives, contribute to their communities, and dreams of a brighter future.

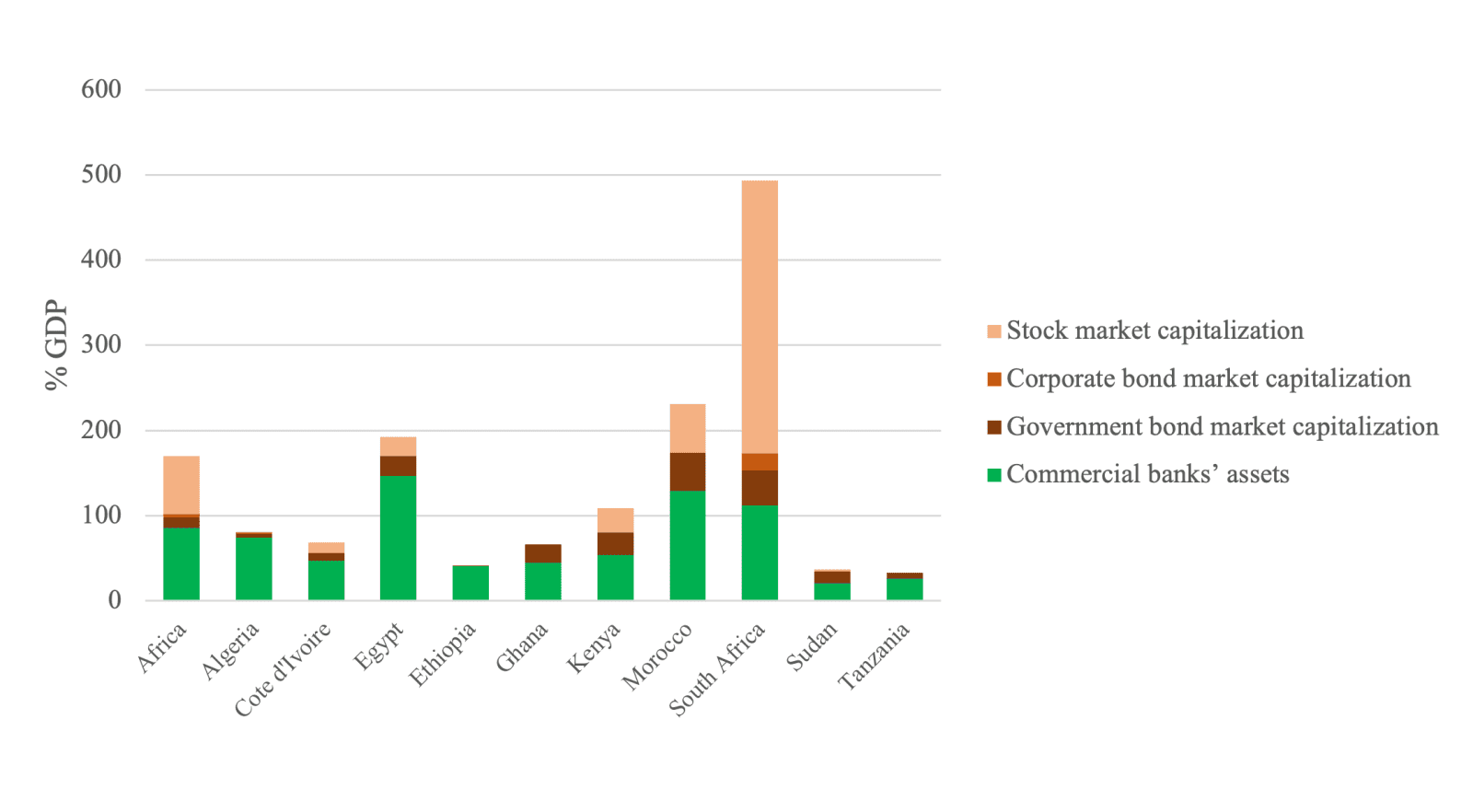

Sources: World Bank (World Development Indicators) and BIS, supplemented by the LTF Survey

Sources: World Bank (World Development Indicators) and BIS, supplemented by the LTF Survey