Setting the scene…

Blink and you might have missed it. But as dusk gave way to darkness on a sunny afternoon in Kigali, UNHCR Livelihoods, Access to Finance Rwanda (AFR) and FSD Africa received a brief but deeply significant email from Equity Bank Rwanda…

“This is to confirm that Equity Bank Rwanda will honor either proof of registration or refugee IDs as valid identification documents [to open a bank account]. We will issue a memo to all our branches to this effect before the end of the week”

18:18, Thursday 22 February, 2018

Kigali, Rwanda

Equity Bank Rwanda

This email marked another milestone for FSD Africa (UK aid’s Nairobi-based platform for inclusive financial sector work in sub-Saharan Africa) almost exactly 12 months of work in a new and important area: the financial inclusion of refugees and other forcibly displaced populations (FDPs).

The recent, rapid growth of FDPs in sub-Saharan Africa has created an urgent need to respond quickly to a complex and dynamic challenge. Through this blog, we wanted to capture what we’ve learned so far so…

Demand-signals: a new way to deliver humanitarian assistance…

Perhaps our most important realisation/conclusion is that refugee settlements are not only hubs for humanitarian assistance. They’re markets, too…

There are buyers and sellers supported by rules and institutions (both formal and informal), especially in larger, older refugee settlements such as Gihembe in Rwanda. And like most markets – these places have failures and pinch-points which inhibit the ability of FDPs to access and use, for example, financial services to help manage their lives.

And while the need for food, shelter and other safety net-type activities will remain, there is now good evidence (from our work and beyond e.g. this study by the IFC, which was featured in The Financial Times) that market-shaping and building has the potential to crowd-in the private sector to profitably deliver some of the goods and services that refugees need and can pay for themselves.

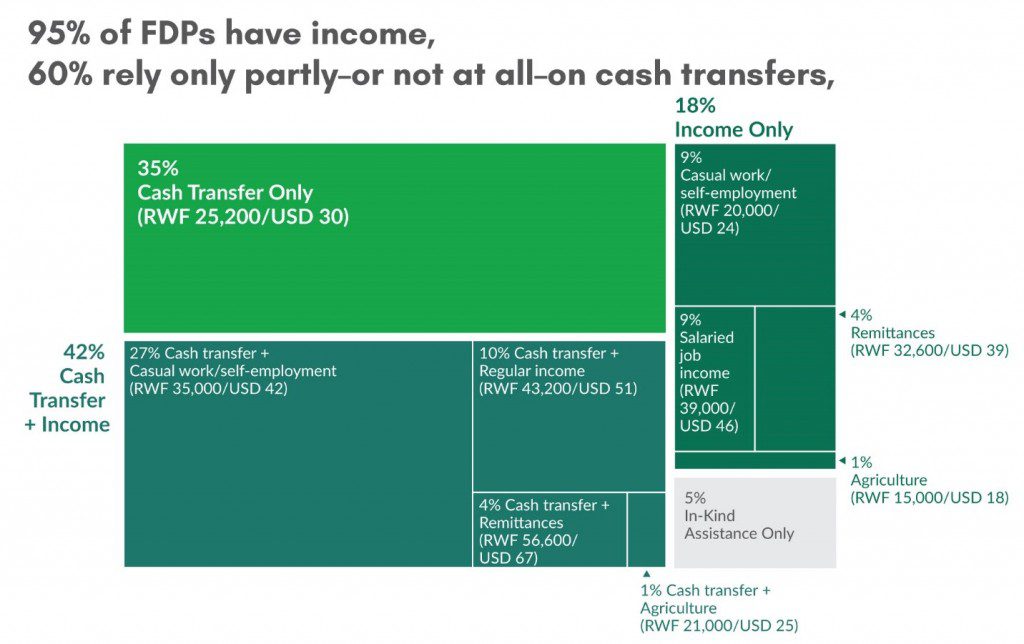

As a quick data point or two from Rwanda, primary FSD Africa and BFA research showed that 90% of refugee households earn $29+/month (the same as the median value of Rwandan bank account holders), while 43% have a secondary school education or more. Globally, 42% of all FDPs have been displaced for 5 years or more.

Identify and experience the market opportunity…

We’ve found that a lack of information is a major challenge. First, refugees are typically viewed by financial service providers as high risk (and low return) clients. Second, they are too often treated as a homogeneous, unsegmented group, dependent on humanitarian hand-outs.

This stereotyping is a tough nut to crack. It involves bridging knowledge gaps, but also long-held attitudes and behaviors. We quickly realised that market intelligence alone – on the financial lives of FDPs and business case for providing FDPs with financial access – just wasn’t enough. Financial services providers needed to see and feel the refugee market for themselves.

In November 2017, FSD Africa, AFR and UNHCR took bank decision-makers out of their offices in Kigali and into a refugee settlement for two nights to develop and test new/existing products, an approach which was replicated by colleagues at FSD Uganda in June 2018.

The transformation was remarkable, and something we started to document, in order to share with other banking decision makers in Kigali, East Africa and beyond.

“It is possible to serve the base of the pyramid, especially refugees, profitably; …I think I may have not necessarily seen the opportunity before I got here”

Patrice Kiiru, Equity Bank Kenya

The power of partnerships…

FSD Africa knew little about this space when we started out. We had theories to test, but little practical experience of accessing camps, refugee politics nor humanitarian assistance more broadly.

The only way we have been able to learn quickly is through the quality of our partners. For UNHCR Rwanda to speak with authority about the power of markets to deliver welfare enhancing outcomes to FDPs was refreshing and impressive in a space historically dominated by charitable giving and direct delivery.

“The way I see it, financial inclusion is really the key to unlocking the economic inclusion”

Jakob Oster, Livelihoods Officer, UNHCR Rwanda

We have built useful partnerships with a wide range of institutions, from commercial banks to charities, and from UN agencies to fintechs. Amongst them, UNHCR is our key humanitarian partner and, through our Innovation Competition FSD Africa and AFR are providing x5 £10,000 accelerator grants to CARE Rwanda, Equity Bank Rwanda, Tigo/Airtel Rwanda, Umutanguha and MFS Africa to develop new solutions to particular challenges faced by refugees. This commitment may be followed to larger investments (up to £150,000) to allow ideas to reach real scale. Beyond this competition, we’re continually looking for opportunities to engage interested, impactful private sector partners.

We have also built partnerships to maximise our local understanding and influence. AFR – a UK Aid, US Aid, Swedish Sida and MasterCard Foundation-funded ‘FSD’ programme for Rwanda – has been an invaluable support. Located in Kigali, with deep connections to the local banking system and regulators, the whole process has been made more effective. Within three months of beginning our work, AFR had successfully lobbied the Central Bank and MIDIMAR to add refugees to the Rwandan Financial Inclusion Strategy.

FSD Africa and AFR have also worked closely with DFID Rwanda.

“Market participation triggers wins for refugees, host communities and hosting governments. This new initiative has been a great demonstration of how to incentivise a market-driven response to a humanitarian challenge.”

Viola Dub, Private Sector Development Advisor, DFID Rwanda

This work falls within the context of a broader Government of Rwanda and DFID Rwanda approach to FDPs. In 2016, Rwanda – as an FDP host nation – signed up to the UN’s Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework, and with DFID Rwanda support is designing a plan for refugee integration.

The host community challenge/opportunity…

A crucial issue that we have struggled to grip is how to integrate host communities – ‘native’ settlements, often poor, rural and located nearby/adjacent to refugee settlements – into our programming. There are a number of stories about host community residents feeling that refugees benefit disproportionately from international aid and government agency support.

This is a difficult balance to strike. It is encouraging to see evidence that local communities benefit from hosting refugee communities, due to higher agricultural opportunities and incomes, but trickle down forces alone seem inadequate. Ensuring we work for host communities as well as FDPs means investing as much in understanding and responding to their specific needs as we do to the FDP. After all, their inclusion in our approach can only bolster the business case adding hundreds of thousands of potential clients.

“I was very surprised, because before arriving in the camps I was not expecting to find some real businesses in the camps; I was surprised to see someone with a business like other Rwandese outside of the camps.”

Theophile Nsabimana, Vision Fund Rwanda

Twelve month conclusions…

One year on, our successes (and failures) may lack the ‘flash-bang’ of a large DFI investment or a VIP launch, but we really can see the emergence of new markets.

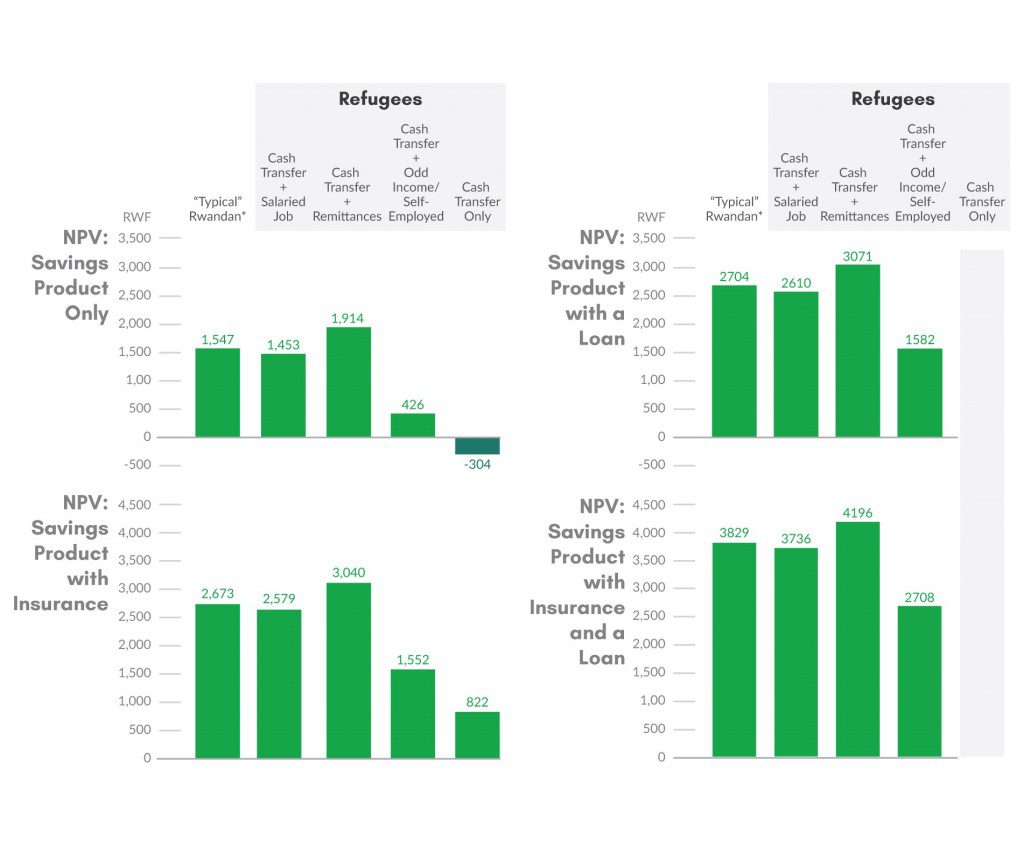

FSD Africa and AFR are now seeding product/solution prototypes by more than five financial service providers in Rwanda. Refugees – young and old, male and female, short-term and long-term displaced – have expressed their demand for financial services to help manage their lives. The National Bank of Rwanda has incorporated refugee finance into its financial inclusion strategy, and banks now better understand that refugee IDs are eligible banking IDs (as per the introduction to this blog).

More broadly, we believe that we’re at the tipping point of genuine behaviour change within the private sector towards this group. FSD Africa and AFR received 23 applications to our refugee finance competition in December 2017, while only last week FSD Uganda and FSD Africa received more than 20 applications by MFIs, banks and fintechs just to visit camps to see the opportunity for themselves. FSD Africa is also about to start work replicating this approach in DRC, through our sister organisation ELAN RDC.

The proof is in the pudding. And we’ll be watching carefully to see: whether refugees can become long-term, profitable clients for the financial sector, but also whether finance can be genuinely useful to forcibly displaced people. But, for now at least, the market is on the move…