Many claim that Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), formally known as Digital Fiat Currency, can have many benefits for financial inclusion and has the potential to impact mobile money. But can CBDC overcome the challenges that current mobile money providers and consumers face?

First things first; what is “Central Bank Digital Currency”. Simply put, CBDC is a digital representation of physical cash. As its digital alternative, CBDC is interchangeable with physical cash on a one-to-one basis as valid legal tender, and adopts all three of cash’s key features: a unit of account; a store of value; and a universally accepted means of exchange between transacting parties. The distinction between CBDC and private cryptocurrencies are summarised below.

Figure 1. Digital Fiat Currency compared to Private Cryptocurrencies

Source: Cenfri, 2018

So, what’s the relevance of CBDC to financial inclusion?

CBDC has the potential to digitise the entire payments value chain, from the first to the last mile in a more cost-effective and efficient way. Cenfri’s 2018 report “The benefits and potential risks of digital fiat currencies” finds that CBDC, unlike cryptocurrencies, can promote adoption through network effects because of the key features that is shares with cash. CBDC’s speed, efficiency and safety (being backed by the Central Bank) introduces much needed trust in digital payment mechanism, something that is lacking in private cryptocurrencies and mobile money. And trust is critical where money is involved. Trust means that CBDC could eventually be adopted along the entire value chain (like cash) and hence could promote financial inclusion at all levels of society.

But what about mobile money specifically?

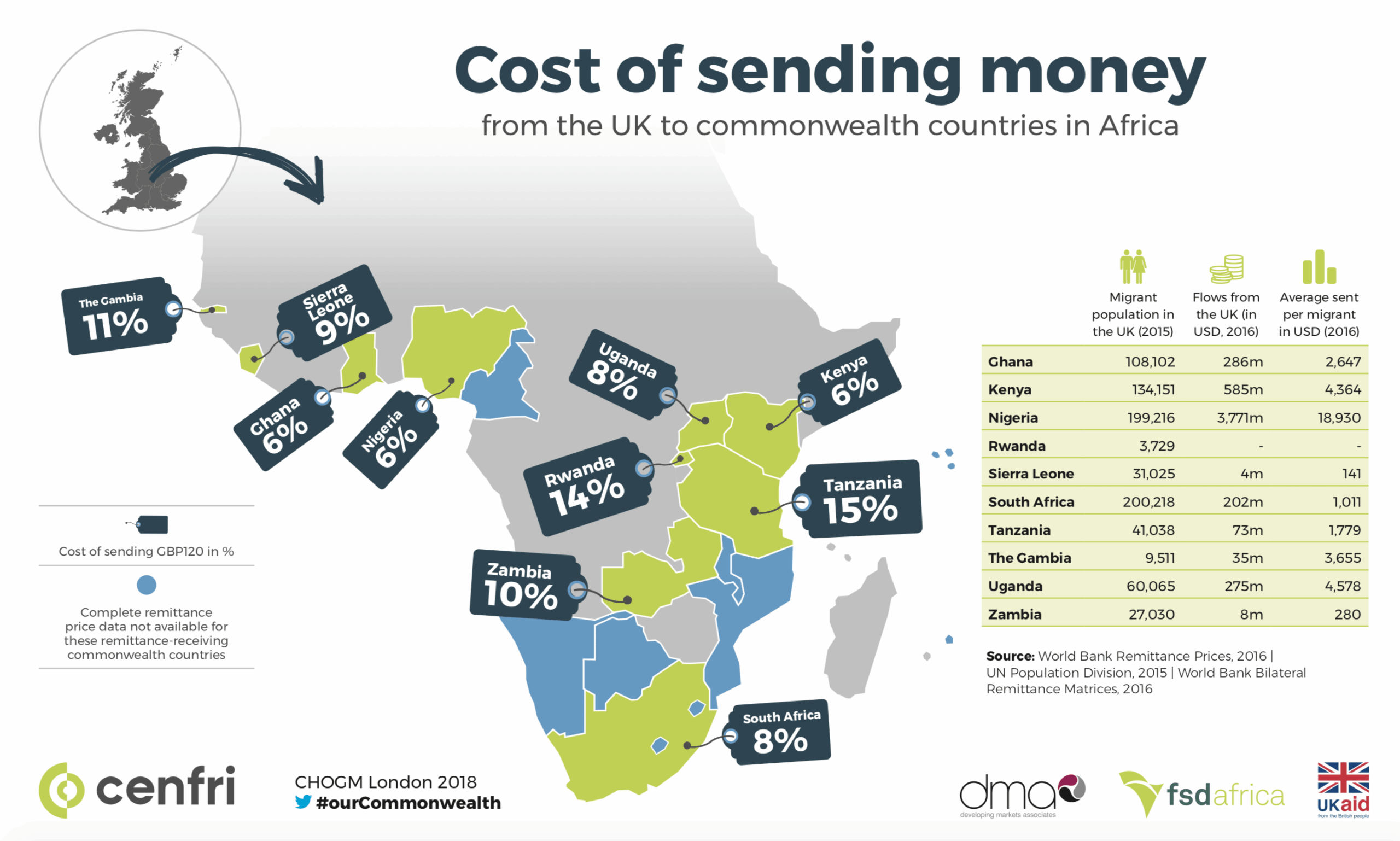

Mobile money may be a leader in “banking the unbanked” but the phenomenon still faces obstacles that undermine its uptake and use, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 2. Key supply and demand cost drivers of mobile money in SSA

Source: Cenfri 2019, based on data from various literature sources

The application of retail CBDC to mobile money can foster greaterinteroperability, improve payment efficiency, facilitate cost-saving gains and reduce key payment risks typically associated with mobile money. CBDC can also enable trust in mobile financial services due to its safety and the way in which its speed eases liquidity constraints of mobile-money agents. CBDC also eliminates the need for unnecessary third-party intermediaries and so streamlines payment clearance at the same time as enabling true interoperability.

How about the downsides of CBDC?

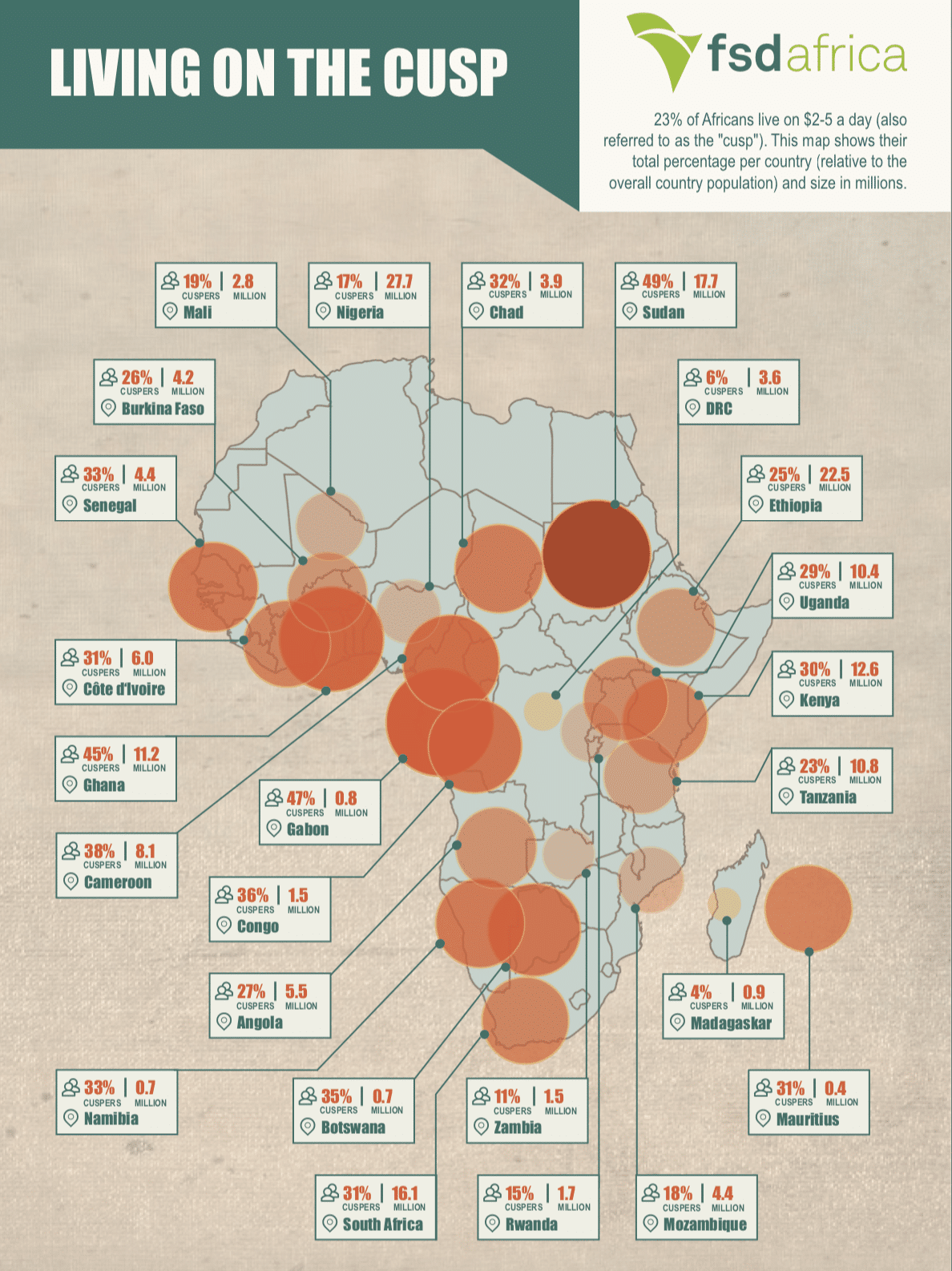

If CBDC is not implemented appropriately it could exacerbate contextual inequalities along the lines of digital, financial and economic disparities between population segments and also intensify the complexity of mobile money. For example, if not everyone has a mobile phone then only those that do can access CBDC; and if only certain areas have network coverage then only those in those areas can access CBDC; and so on. CBDC could threaten the intermediation role of traditional deposit-taking. CBDC could also exacerbate poor uptake of mobile money (e.g. due to illiteracy) simply because of CBDC’s (perceived) complexity. If everywhere you can only pay in CBDC then it may make the gap between illiterate and literate users even wider. The more vulnerable segments of the population, as primary unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) customers, could also be at greatest risk of identity fraud.

So what can be done to avoid these risks?

CBDC can bring maximum benefits to mobile money and financial inclusion if it meets certain pre-conditions. The basic principles to avoid these risks lie with governments and the enabling financial environment they create in their respective countries. Governments need to ensure appropriate and effective legislation and anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism regulation, as well as the implementation of robust consumer protection laws and national cyber-security defences. We know that that some developing economies lack these key laws – or lack the ability to uphold the legislation, even if it does exist. Through our Risk, Remittances and Integrity Programme, FSD Africa is partnering with Cenfri to combat these challenges by helping countries implement appropriate regulation that enables low-cost, efficient, domestic and cross-border payments to enable inclusive financial systems to operate at scale, and positively impact broader economic development.

It’s clear mobile money presents a significant use case for CBDC in the drive towards financial inclusion, but not without risks. If governments, supported by development partners, address these concerns, the impact of CBDC on mobile money could not only be positive, but could also contribute to significantly greater financial inclusion and better economic integration altogether.

You can delve deeper into the role of CBDC in delivering financial services to the unbanked and CBDC’s applicability to mobile money by downloading Cenfri’s latest report “Central Bank Digital Currency and its use cases for financial inclusion; a case for mobile money”.