Join us in celebrating International Women’s Day 2018!

Through our #PressforProgress campaign, we are proud to share information about our partnerships that are supporting women’s economic empowerment in a variety of ways.

,

,

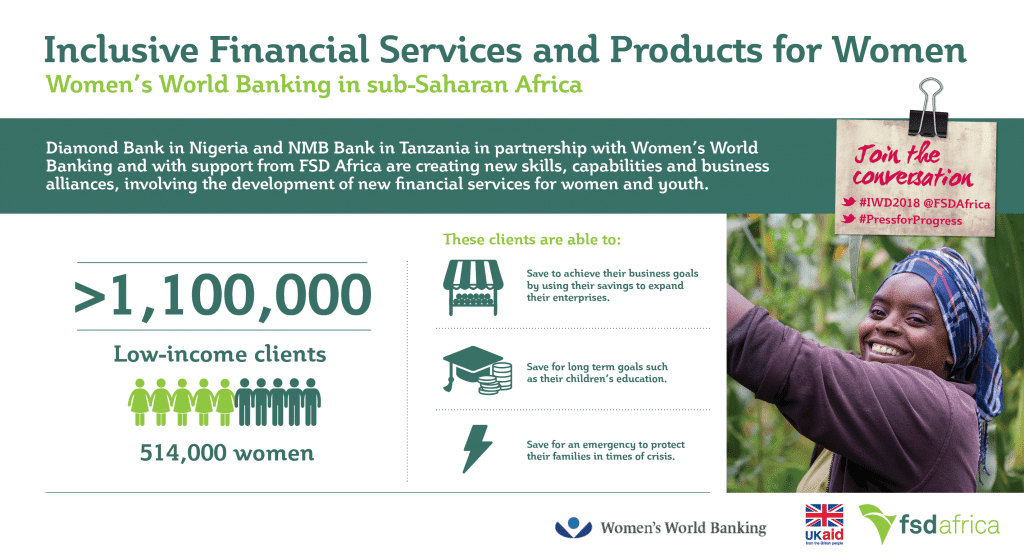

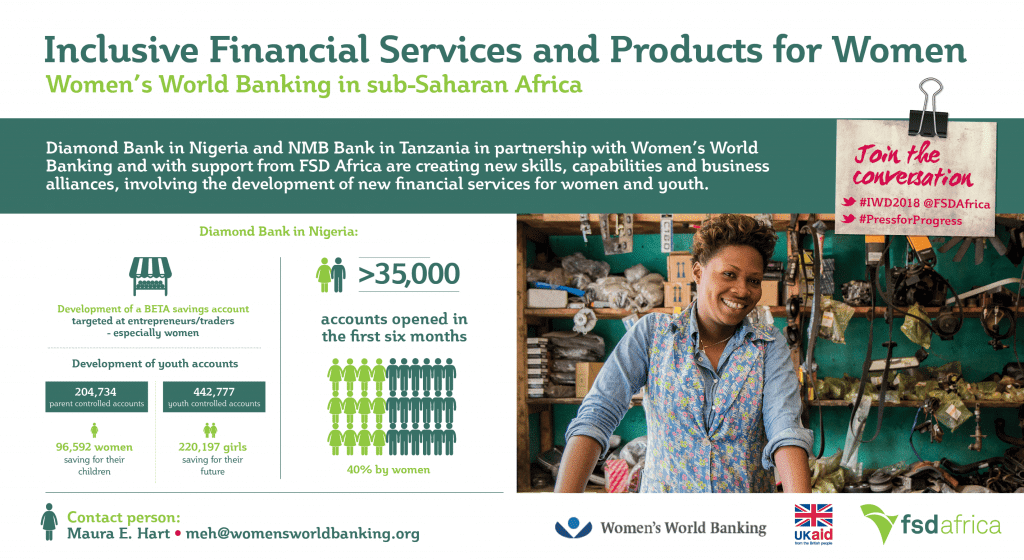

Through our #PressforProgress campaign, we are proud to share information about our partnerships that are supporting women’s economic empowerment in a variety of ways.

,

,

Through our #PressforProgress campaign, we are proud to share information about our partnerships that are supporting women’s economic empowerment in a variety of ways.

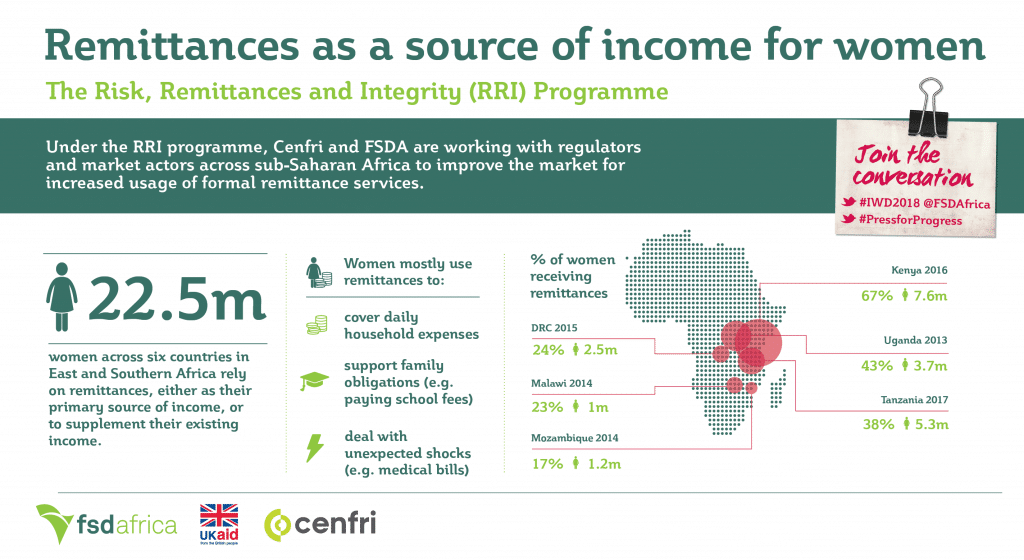

Cenfri supports financial inclusion and financial-sector development through facilitating better regulation and market provision of financial services through research, advisory services and capacity-building programmes. FSD Africa and Cenfri have partnered on the Risk, Remittances and Integrity (RRI) programme which seeks to strengthen the integrity and risk management role of the financial sector and to facilitate remittance flows within and into the continent.

With respect to remittances, research conducted by Cenfri indicates that remittances are an important source of income for women in sub-Saharan Africa. They are used to meet monthly expenses, deal with unexpected shocks, and support family obligations (e.g. paying school fees).,

Through our #PressforProgress campaign, we are proud to share information about our partnerships that are supporting women’s economic empowerment in a variety of ways.

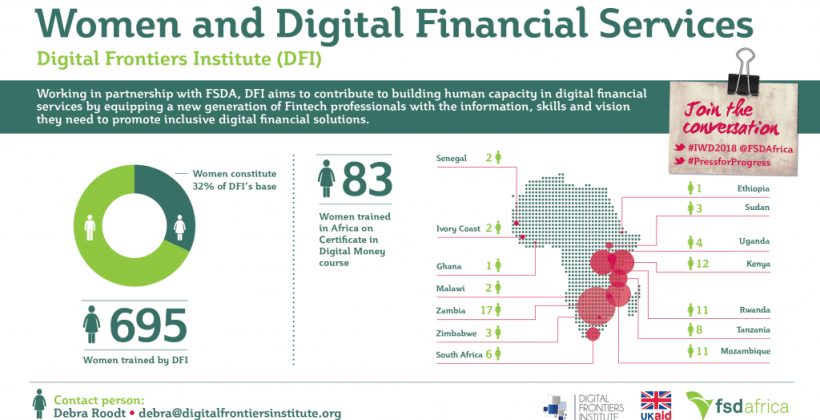

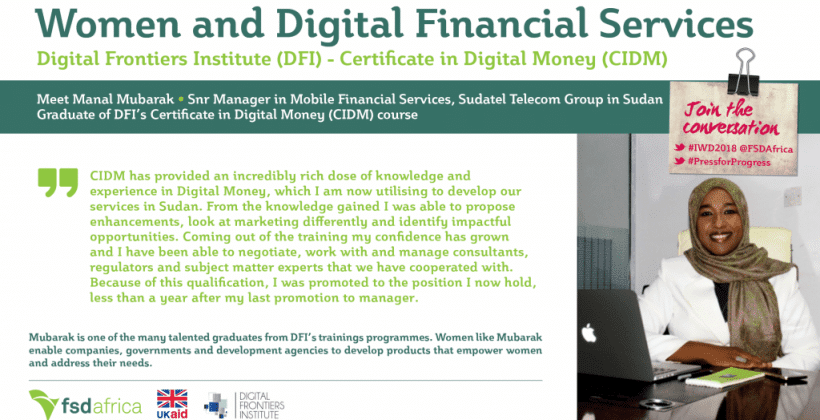

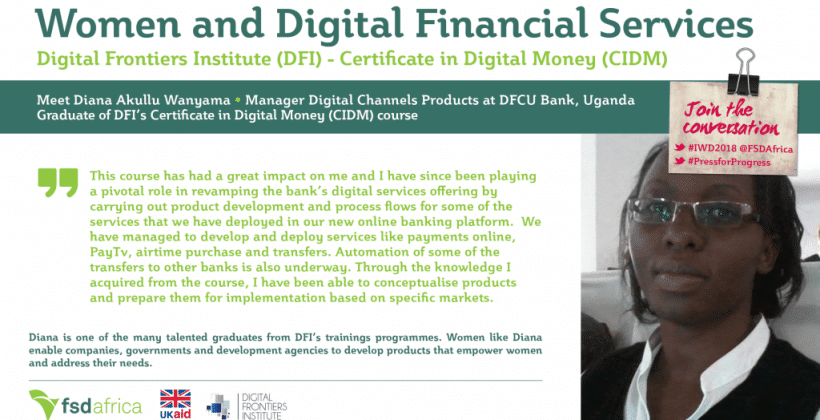

The Digital Frontiers Institute is a one-of-a-kind institution that is building human capacity in digital financial services by equipping a new generation of fintech professionals with the information, skills and vision they need to deliver and guide society towards inclusive digital financial solutions. DFI recognises the under-representation of women in leadership roles in digital financial services and fintech as well as the general lack of financial inclusion for women across the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Through support from FSD Africa and other partners, DFI is addressing these issues by equipping women with the necessary qualifications and training to develop digital financial services and products that sustainably include them and that, in turn, allow women actively participate in the economy.,

In early November, FSD Africa brought two worlds together for the first time: taking five prominent financial service providers (FSPs) to Gihembe Refugee Camp in Rwanda to participate in a ‘Financial Product Design Sprint’ in partnership with UNHCR, Government of Rwanda, and Access to Finance Rwanda (AFR). We were also joined by a member of UNHCR from Geneva, the International Finance Corporation and FSD Uganda.

Earlier that week, FSD Africa and BFA presented research on ‘Refugees & Their Money’ to over 20 FSPs in Kigali – highlighting the business case for financial products focused towards refugees (you can find a short summary found here). Philip Kakuru, from Tigo, said ‘With the limited access of the refugees, there was little to know about them, but the sprint design opened our eyes’. These FSPs, along with any others, now have an opportunity to win one of our four £10,000 grants in our Innovation Competition – Financial Services for Refugees in Rwanda.

To read more about the wider FSDA approach to refugee finance, take a look at last month’s blog here.

The next day, the five FSPs, chosen through an open competition, began the Financial Product Design Sprint. The FSPs were a diverse group representing MMOs, MNOs, MFI and banks: MobiCash, Equity Bank, Vision Fund, Tigo and Commercial Bank for Africa. This three-day event hoped to challenge misconceptions about refugees, their potential and FSPs to consider a refugee product seriously. The first day began with an in-depth presentation of BFA’s research and details regarding the structure of refugee camps. This was followed by product brainstorming with each FSP, before narrowing down to a select two or three ideas which were fleshed out.

On the second day, these FSPs were taken to Gihembe Refugee Camp, a camp with a population of around 12,000 refugees from DRC and located only an hour drive from Kigali. Here, each FSP had the opportunity to speak to at least two refugees and over the course of two hours get a better feel for their financial lives. For most, this was their first time interacting with refugees and particularly in a refugee camp. As one FSP noted ‘With this segment, there is a lot to offer and learn from them’. This was followed by further prototyping of the FSP’s idea and customising their product to the needs of refugees.

The final day offered an opportunity to return to the camp and with initial prototypes, in the form of a drawing, poster or app, get direct customer feedback. This proved particularly helpful for many FSPs to refine their product. As Peter Kawumi, from FSD Uganda, said ‘Through the design sprint’s customer interaction iterations, misconceptions about the refugees’ technology literacy, economic independence and financial ambition were debunked.’

The first ‘Financial Product Design Sprint’ was well received by all FSPs and there is also potential for replication in Uganda, with FSD Uganda, and as Vishal Patel from the IFC said ‘helped inform IFC’s work in Kenya in Kakuma refugee camp and town.’

Learning from risk taking

Working with banks and beneficiaries in this way is new to FSD Africa. It builds on the FinDisrupt model, pioneered by our sister organistion – FSD Tanzania. We learned a lot, especially on the value of bringing the refugee voice into FSD Africa planning and FSP business casing. The type of discussion it generates, out of the office environment, created momentum that would otherwise never have been achieved.

To read more about the wider FSDA approach to refugee finance, take a look at last month’s blog here.

Cathy pauses by the window of her fifth-floor office to look at the rain clouds gathering and the traffic beginning to build. It is four o’clock in the afternoon and her boss has just walked in to ask for a ‘short’ team meeting. She is anxious; an important customer has just called to query some figures in his bank statement and wants it addressed by the end of the day.

A mother of two, Cathy has recently enrolled for an executive MBA programme at a local university. Her classes start at 5:30 p.m. and she knows only too well that she has to leave the office by 4:45 to beat the traffic. A few months earlier, during her performance review, her boss told her that she needed to improve her qualifications to advance further into management. But a colleague of hers, who got a promotion after completing an MBA, recently had a bad review. She wonders if taking the executive programme will be worth all the effort.

Will Cathy’s investment in executive education improve her career prospects? Will it lead to rease? And will her newly acquired skills improve her day-to-day job performance? In 2016, FSD Africa commissioned research to assess the impact of executive education in financial services firms and to help answer these questions.

On the subject of pay, it found that many employees with ExEd qualifications do not feel their salary is commensurate with their education, especially as many have had to pay fees to advance their studies. ExEd graduates do report, though, that they are more mobile in terms of career prospects than their peers. Importantly, managers respect the work of employees with ExEd qualifications, reporting that they perform well and are innovative – particularly in terms of applying the skills they acquired to problem solving.

Qualitative data from the report indicates that ExEd employees in financial services firms improve the image of their organisation and play a key role in shaping customer perceptions of it. What’s more, both employee and manager groups reported that ExEd is particularly effective in improving customer service skills – and therefore increasing customer satisfaction.

The research recommendss in the delivery, scope and content of executive education, in order to address the needs of the financial sector. The most important of these is that ExEd should be more practical in nature, instead of focusing so heavily on theory. In addition, longitudinal research is necessary to measure the impact of executive education programmes on students and organisations. And lastly, improvement is needed in performance measurement within financial services firms, in order to better demonstrate the link between ExEd and performance, pay and mobility.

Click here to download the full report: ‘The Impact of Executive Education in sub-Saharan Africa’.

Written by Dr. Moses Ochieng, Consultant-Professional Skills Development, FSD Africa<

Alex is a mid-manager at an NGO in Nairobi. He’s servicing a home loan for a two-bedroom apartment in an upmarket neighborhood, and two car loans – one for him and one for his wife. His four-year-old son is in a private nursery school and Alex is considering enrolling him in a private elementary school next year.

Two years ago, he took another loan to buy the land where he intends to build his family home. The land is 50 kilometres from the main road and the access road is yet to be paved. None of the owners of other plots near his have considered developing their properties but there are plans to connect electricity and water.

The family goes on holiday twice a year – again, financed through personal loans. Alex is also financially responsible for taking care of his elderly mother, who has no income and lives in the village. On top of that, he pays for his younger sister’s college education; she’ll be finalising her diploma course in the next two years. He also employs his cousin, who recently of college, in a small business Alex started to supplement his income.

Since he has a pay slip and a contract of employment, the bank considers Alex to be a good customer and often tops up his home loan whenever he faces financial pressure. In addition, Alex is a member of a SACCO. He has a loan there, as well as two peer groups – one is a welfare group and the other is an investment club.

With all this to consider about Alex’s background, how can the bank properly assess the risk of lending to him? Risk management practices vary from bank to bank depending on their policies on granting credit. Poor credit risk management can lead to institutional failure. This, in turn, can reduce financial inclusion.

In 2016, FSD Africa commissioned a market study to assess demand for, and supply of, risk management training for the financial sector. The study looked at three markets: DRC, Ghana and Kenya.

It found that in most institutions, after a brief orientation or introductory course, new staff members are puto operations without appropriate skills training. In a majority of institutions surveyed, no risk management training is provided to entry-level staff (those in their first or second year at the institution).

Not surprisingly, most institutions cited poor portfolio performance as a symptom of poorly trained staff. But the importance of entry-level training is still underestimated. Entry-level staff are the foundation of any financial sector. Without strong skills at the foot of the staff pyramid, middle managers struggle to control risk in daily operations. And in addition to strengthening risk management, better entry-level staff training can lead to an improvement in the quality of customer service.

How, then, can such training be improved? Above all, the study recommends the development of a comprehensive risk management training programme. This would address risk management training needs, particularly for entry-level staff, and help them to stem the rising tide of bad loans.

In August 2017, FSD Africa launched a fresh drive to build measurement know-how across the FSD Network – a family of ten like-minded financial sector development programmes across sub-Saharan Africa funded by UK Aid. These projects – the development of a Value for Money (VfM) framework & the development of a compendium of indicators for financial sector development interventions – are the latest departure in a journey that began just over three years ago. This blog tells its story…

Over the last two decades, the role of Monitoring and Results Measurement[1] (MRM) in the field of international development has become more and more critical. The presence of MRM systems within organisations implementing development projects, irrespective of the strength of such systems, is now more the norm than the exception. Though MRM remains an important accountability tool, what’s more striking is the increasing role it plays in the ways in which interventions are planned, designed and implemented by development practitioners. Thus, MRM systems have many stakeholders – from funders and board members to project managers and delivery partners – and they need to be robust enough to meet their various needs.

While it’s critical to make MRM systems robust and efficient, achieving this is not an easy undertaking. It requires financial investment, commitment at CEO-level and the wider team, and continuous learning and improvement. This has very much been the case for the FSD Network.

Investing in stronger MRM systems began in earnest in July 2014, when FSD Africa began an FSD network-wide consultative process aimed at strengthening MRM processes within individual FSDs, both at project and programme level. The initiative also sought to achieve a more consistent approach to MRM across the FSD Network, one that would spur seamless cross-learning amongst its members. The result of this extensive consultation was publication of the Impact Orientated Measurement guidance paper, or IOM, which was launched in December 2015.

The launch of IOM, was an important milestone; one that was received with mixed feelings – of both excitement and anxiety. A vision of what an effective MRM system looked like was clearly established in theory, but the delivery of one in practice – across the FSD Network – quickly became FSD Africa’s challenge. This has required systematic effort over recent months since its launch.

Here’s what we did…

First, MRM diagnostic clinics were undertaken between April and July 2016, in partnership with Genesis Analytics. The objective of this exercise was to determine the readiness of FSDs to implement IOM. It involved evaluating the status of the different FSD MRM systems, as well as establishing the knowledge and attitudes of staff, senior management and governing bodies towards MRM, and more specifically IOM. Light-touch tailor-made support was also offered during these clinics, benefiting 47 FSD staff. Through this exercise, FSD Africa gained a better understanding of the unique needs of each FSD and their perceptions on how to address these challenges. By and large, it also provided an opportunity for individual FSDs to decipher IOM and define how they could start applying it.

Second, based on findings[2] from the MRM diagnostic clinics, FSD Africa worked with Adam Smith International to develop and deliver a 2.5-day training course christened Results Measurement for Systems Approaches in Financial Sector Deepening. The training, which took place in November 2016, focused on the five principles of IOM[3]. In total, 20 FSD staff drawn from FSD MRM units, intervention teams and programme management benefited.

One unexpected, but positive outcome of the MRM training was an increased appetite for FSD-specific MRM support, delivered through in-country support to staff. Two FSDs (FSD Uganda and FSD Mozambique) have so far benefited from this initiative. The results are evident – FSD Uganda now has an IOM-enabled MRM manual, and staff with a greater understanding of how to plan and execute results measurement initiatives. Its Board of Directors has a better appreciation of the intricacies of implementing and measuring results of projects that utilise the M4P approach, and are willing to support the course. FSD Mozambique has also just embarked on a process of reviewing its own results measurement guidelines and tools.

FSD Africa appreciates that, though IOM is a useful conceptual cornerstone, it is no panacea for measuring the results of complex financial sector development programmes. There is need to augment it with practical tools that can be easily deployed across the FSD Network.

In response, in August 2017, FSD Africa commissioned two other initiatives, which are being delivered in partnership with Oxford Policy Management:

Amidst all these developments, is a thriving MRM Working group – an experience-sharing platform for MRM staff across the FSD Network. FSD Africa acts as its secretariat. The Chair rotates between individual FSD MRM leads.

Has this been an easy-to-execute task? Not at all. But, substantial progress has been made. In my next article, I will reflect on the lessons FSD Africa has learned during our work towards a harmonised MRM approach across the FSD Network.

——

[1] Also commonly referred to as Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E)

[2] A generally poor comprehension of the value of Theories of Change in effective results measurement, as well as insufficient skills in applying the same; widespread desire to understand how to effectively measure systemic change; weakness in assessing causality and building credible ‘contribution’ narratives; infrequent and meaningful engagement between some MRM units, intervention teams, and programme/organizational management.

[3] Aligning monitoring with measuring impact (the ‘sweet spot’); using the ToC as a strategic framework for planning and impact evaluations; focusing on the FSD programmes primary interest (as regards measurement), which is assessing changes in inclusive financial markets; identifying and measuring systemic change; measuring impact from the perspective of both the FSD programme (‘bottom-up’) and the sector/market system (‘top-down’)

When taking a market systems approach, development organisations such as those in the FSD network act as facilitators of market development—external change agents whose role is to develop actors in the market system to increase financial inclusion.

While facilitators work in a variety of ways, their primary role is to address constraints, in order to allow and facilitate the market system to function more effectively and inclusively. Facilitation is therefore a public role (not a commercial one); it is a temporary role (it is time-bound); and it requires understanding of the market system and the capacity to intervene with appropriate resources (financial, human and political).

The purpose of this paper is to provide guidelines on some key, practical questions facing facilitators, based on synthesised learnings from the FSD Network as captured in seven case studies written by the Springfield Centre. This document explores the art of market facilitation in action through the lens of the FSD network to bu understanding around the M4P approach. The paper examines the wider lessons and challenges that emerge for organisations addressing the dilemmas of developing financial markets for the poor, and how they differ significantly from other conventional approaches.

We hope that you find the learnings in this synthesis paper useful and that they shed some light on your path to effective market facilitation.,

For insurers to serve a new type of client at scale they must change their modus operandi. The high costs associated with conventional insurance cannot be absorbed by low premium products. This means that existing structures need to be adapted to serve the low to middle-income mass market.

One key to success lies in digitization, which can be used to automate existing (often paper-based) processes. Going digital has obvious benefits: minimising expenses, reducing the scope of human error, improving efficiency and achieving scale. But, how can insurers begin to make this shift?

Working with our partner Britam in Kenya, we have seen one route to becoming a digitally-driven insurer: start with strategic process mapping.

So what does a strategic approach to process mapping look like? Process mapping involves creating a flow chart to capture every step in a process. This is then analysed to see how the process could be redesigned. Process mapping can both reveal opportunities for automation and help manage the internal change required to put it into action.

The strategic element of process mapping lies in identifying how new processes can achieve greater efficiency and also help improve the client’s experience. The ILO’s Impact Insurance Facility advocates

To illustrate, let’s take a simple example. At Britam, one of the team’s many tasks was to redesign the member information gathering process at enrolment to cut data entry and courier costs. The team started by looking at the systems and resources in place to capture data, and the experience of internal and external stakeholders interacting with the system. Careful analysis from both “outside-in” and “inside-out” uncovered pitfalls and opportunities for automation of members’ enrolment data gathering, such as customers processing their own data through an automated platform.

However, there are limits to automation, including limited client access to internet and smart phones. This problem extends to partner organisations, who are in many for automated processes. For example, the mission hospitals who work with Britam prefer paper claims submission.

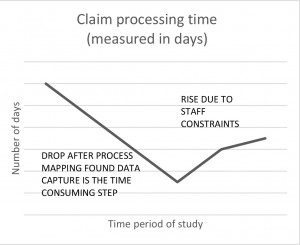

Furthermore, there may be initial teething problems with automation, especially when it is only partial and still relies on a degree of human intervention. For example and as illustrated by the graph, after making significant reductions in claims processing times through process automation, Britam found that the processing time started to increase again due to staff constraints. This highlighted the need to support process changes with training or new staffing structures.

Our change management projects have repeatedly shown that digitization success does not lie solely in introducing technology, but in how people are placed to handle this change. Understanding what it takes to encourage and sustain behavioural change, both internally and externally, is key to change management and to reaping the rewards of going digital.

This blog is part of a joint series between the ILO’s Impact Insurance Facility and FSD Africa. The series explores practical solutions to manage change within insurance providers.