- COP27 may be over but its impact will be felt for many decades to come.

- Discussions highlighted nature’s pivotal role in tackling the climate crisis.

- Here we reflect on 10 areas where progress is being made on climate action.

The implications of COP27 will likely be felt for decades to come, for better or worse. While a broad range of analysis has already been published on the ultimate outcomes of COP27, this summary includes reflections on how nature was the stand out topic at COP27 – here are the top ten takeaways.

1. Calls for structural reform of finance for nature and climate

It was impossible to pass a day at COP27 without having a conversation about finance – but finance means different things to different people. The breakthrough on loss and damage funding made the headlines, but this year there was much attention on structural reform of the financial system as well as the need to create innovative mechanisms that support nature and climate outcomes at national and ecosystem levels.

The Bridgetown agenda remained a central theme within these discussions. Before COP27, there was much focus on the need for financing adaptation measures – although in fact, very little progressed on this agenda from Glasgow. The multilateral development banks are also under scrutiny – sovereign bonds and sustainability-linked loans and bonds have been high on the agenda. Leading financial institutions from Japan to Norway to Brazil, all signatories to the Financial Sector Commitment on Eliminating Commodity-driven Deforestation have been moving forward with implementation through the Finance Sector Deforestation Action (FSDA) initiative.

FSDA members have published shared investor expectations for companies, and they are stepping up engagement activity and are working with policymakers and data providers. More broadly, the 10 point plan for financing biodiversity moved ahead at COP27 with a ministerial meeting between 16 countries representing five continents to set a pathway for bridging the global biodiversity finance gap – and looking ahead to the biodiversity COP15 in December 2020.

2. Biodiversity COP15 looms large

The biodiversity COP is usually a distant cousin to the climate COP, but in Egypt there was a considerable amount of attention on the need to create a “sister agreement” – a Paris moment for nature. The messaging that the climate and nature crises are deeply linked was made loud and clear at COP27.

On Biodiversity Day, the Paris climate champions urged leaders to step up action to address the accelerating loss of nature by delivering an ambitious biodiversity agreement at COP15 in Montreal. On the same day, more than 340 civil society leaders called on governments to prioritise the biodiversity COP, and a new survey from more than 400 experts from 90 countries revealed that a shocking 88% believe that the state of the world’s nature is “alarming” or “catastrophic and potentially irreversible”.

However, even though many countries were pushing for COP15 to be included in the COP27 text, the attempt failed – a disappointing outcome as net-zero emissions will not be enough to limit rapidly rising temperatures. Governments also need to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030.

3. Strong signs of political will for forests

The creation of the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership (FCLP), announced at the World Leaders’ Summit, is being driven by the reality that there is no time to lose when it comes to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030, with the intent to demonstrate success by COP28. The leaders of the 28 – and counting – FCLP member countries serve as key actors in the partnership, and its ultimate priority setters.

The FCLP will hold regular meetings, including leader-level moments at the beginning of climate COPs to encourage accountability. Starting in 2023, the FCLP will also publish an annual Global Progress Report that includes independent assessments of global progress toward the 2030 goal, as well as summarising progress made by the FCLP itself, including in its action areas and initiatives.

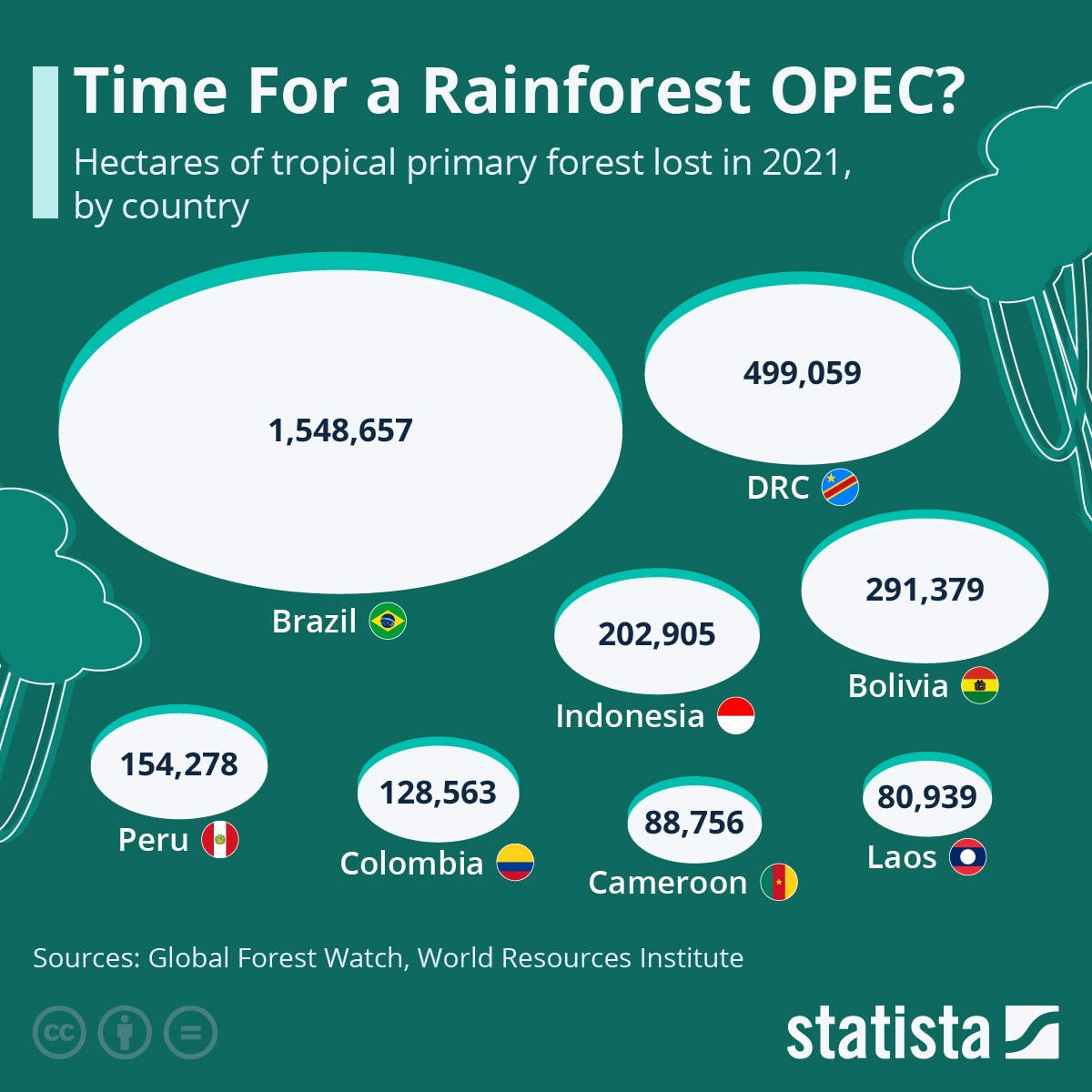

The presence of Brazil’s president elect, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, put a spotlight on the Amazon at COP27 – with Brazil promising to prioritise stopping deforestation and offering to host COP30 in three years’ time. Also, an announcement by Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo – made in Indonesia ahead of the G20 – signalled their intentions to work together to protect their vast swathes of tropical forests, earning the nickname “the OPEC of rainforests”.

This chart shows the total hectares of forest that have been destroyed in different countries. Source: Statista.

4. Implementation of forest pledges

Coming into COP27, there were clear signs that the global community is not yet on track to halt and reverse forest loss and degradation by 2030. Another UN-led report found that for 2030 goals to remain within reach, a one gigaton milestone of emissions reductions from forests must be achieved not later than 2025, and yearly after that, but that current public and private commitments to pay for emissions reductions are only at 24% of the gigaton milestone goal.

However, it wasn’t all bad news on the implementation front. Nature4Climate’s new joint commitment tracker found that 55% of the commitments tracked are demonstrating substantial signs of progress. There are also some bright spots to celebrate. For example, tropical Asia is on the path toward reversing forest loss by 2030: Indonesia’s deforestation rate dropped by 25% last year, and Malaysia also reported a fall of 24% in the pace of forest loss last year.

Forest pledges made in Glasgow at COP26 were also in the spotlight. In 2021, $2.67 billion was put towards forest-related programmes in developing countries – 22% of the $12 billion pledged at COP26, meaning that donors are on track to deliver by 2025. Private sector funds are also moving: for example, one year after launch, the IFACC initiative is scaling innovative financial mechanisms to help farmers without further conversion of the Amazon, Cerrado and Chaco ecosystems.

So far, commitments have risen from $3 billion to $4.2 billion and disbursements are expected to exceed $100 million this year. Similarly, the public-private LEAF Coalition has mobilised an additional $500 million in private finance, bringing a total of $1.5 billion in support of tropical forest protection. This is part of $3.6 billion of new private finance announced at the climate summit.

And exciting private sector initiatives worth noting include the launch of a new company Biomas (by Suzano, Santander, Itau, Marfrig, Rabobank and Vale) to restore 4 million hectares in the Amazon, the Mata Atlantica rainforest and the Cerrado. Also, 1t.org announced pledges from its first four Indian companies (Vedanta, ReNew Power, CSC Group and Mahindra) to join 75 other companies worldwide committed to planting and growing 7 billion trees in more than 60 countries.

5. Nature of negotiations

In the negotiations, nature-based solutions were included in the COP27 text for the first time, with forests, oceans and agriculture each having their own section. The Koronivia Dialogue – the track where food and agriculture is discussed at the UNFCCC – has finally been included in the text, but all eyes turn to COP28 for the focus required to truly transform food systems.

In the wonderful world of Article 6, things remain complex. Last year, at COP26 in Glasgow, countries decided on the basic framework of Article 6. Throughout 2022, countries have been focused on how to operationalise the Article 6 mechanism that allows countries to actually begin trading. In Egypt, the discussions were very technical – such as how registries are going to work, how countries will report on the trading, and what information should be submitted –with the aim of making things easy to track.

For nature, it was decided at COP26 that land use emissions were part of Article 6 – as it includes all sources and sinks. The focus in Egypt has been on article 6.4 – the mechanism for developing guidance on activities involving removals which includes reforestation, restoration, afforestation etc.

6. Technology meets nature

In a similar way to finance, “tech” gets everywhere at climate COPs, although historically that is not really the case when it comes to nature – not this year however. In Egypt, the need for high-tech solutions for nature and climate challenges was a constant refrain. The role of tech in improving transparency and accountability in monitoring supply chains (and tackling deforestation) and also in enhancing the integrity of carbon markets was evident everywhere.

Notable developments include Verra’s partnership with Pachama to pilot a digital measuring, reporting and verification platform for forest carbon. A new Forest Data Partnership was announced by WRI, FAO, USAID, Google, NASA, Unilever and the US State Department. WRI’s Land and Carbon Lab was on show demonstrating the new frontier of measuring carbon stocks and flows associated with land use.

Nature4Climate demonstrated a beta version of its new online platform (naturebase) to help decision makers implement natural climate solutions. And the new Global Renewable Energy Watch – a partnership between The Nature Conservancy, Microsoft and Planet – was also demonstrated. Capturing this emerging trend, Nature4Climate and Capital for Climate launched a report on the size and potential of the whole “nature tech” market that was discussed at an event in the Nature Zone.

7. Food finally arrives on the scene

Food was on everyone’s mind at COP27 in Egypt – but for the first time, it also made it onto the main agenda – being recognised in the final text and also with at least five event spaces solely dedicated to food and agriculture.

Important developments included the Food and Agriculture for Sustainable Transformation Initiative (FAST) launched by the Egyptian COP presidency – a multi stakeholder partnership to accelerate access to finance, build capacity and encourage policy development to ensure food security in countries most vulnerable to climate change.

Also related to food, 14 of the world’s largest agricultural trading and processing companies shared their roadmap to 1.5℃ – to mixed reactions – with detailed plans on outlining how they will remove deforestation from their agricultural commodity supply chains by 2025.

8. An increasingly blue COP

Observers have expressed encouragement at this being “an increasingly blue COP”, with the ocean called out in the final declaration and the first ever ocean pavilion in the blue zone. Several declarations reinforced the recognition of the fundamental role of the ocean in the climate system.

The Egyptian presidency, Germany and IUCN launched the ENACT initiative (Enhancing Nature-based Solutions for an Accelerated Climate Transformation). The Mangrove Breakthrough was launched to protect 15 million hectares of mangrove globally by 2030. And the High Quality Blue Carbon Principles and Guidance were also announced.

9. Indigenous peoples and local communities

The critical role that Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) play as guardians of the forest is now firmly established and beyond question. At COP27, there was a polite but palpable frustration from IPLCs that climate funds are not reaching them. This massive deficit is increasingly being acknowledged by both by Indigenous and non-Indigenous actors, with a wide range of events dedicated to this topic.

While COP27 was a good space for Indigenous and non-Indigenous actors to share knowledge, to listen deeply to one another, to build relationships, it clearly can’t be the only space. While there are a number of encouraging signs of progress, including linking IPLCs with high-integrity markets, it’s clear the clock is ticking and IPLCs are getting impatient.

Clearly we must act with urgency, but it’s critical to take the time to build trust and mutual understanding, including absolute adherence to free, prior and informed consent protocols. This is necessary so that IPLCs can decide (or not) to participate in carbon markets with transparency, full understanding, and free consent. This takes time.

10. African-led initiatives take centre stage

While this was not the “African COP” that many hoped it might be, there were still a range of significant announcements coming out of Egypt that highlighted the continent’s potential as a natural capital powerhouse. These included the launch of the Africa Carbon Markets initiative, the Declaration for the Africa Sustainable Commodities Initiative, the launch of a $2 billion African restoration fund, a funding boost for Africa’s visionary Great Green Wall initiatives, and the announcement by the Global EverGreening Alliance and Climate Impact Partners of a new partnership to up to $330 million in community-led removal programs across Africa and Asia.

Read original article