Join us in celebrating International Women’s Day 2018!

Through our #PressforProgress campaign, we are proud to share information about our partnerships that are supporting women’s economic empowerment in a variety of ways.

,

,

Through our #PressforProgress campaign, we are proud to share information about our partnerships that are supporting women’s economic empowerment in a variety of ways.

,

,

Through our #PressforProgress campaign, we are proud to share information about our partnerships that are supporting women’s economic empowerment in a variety of ways.

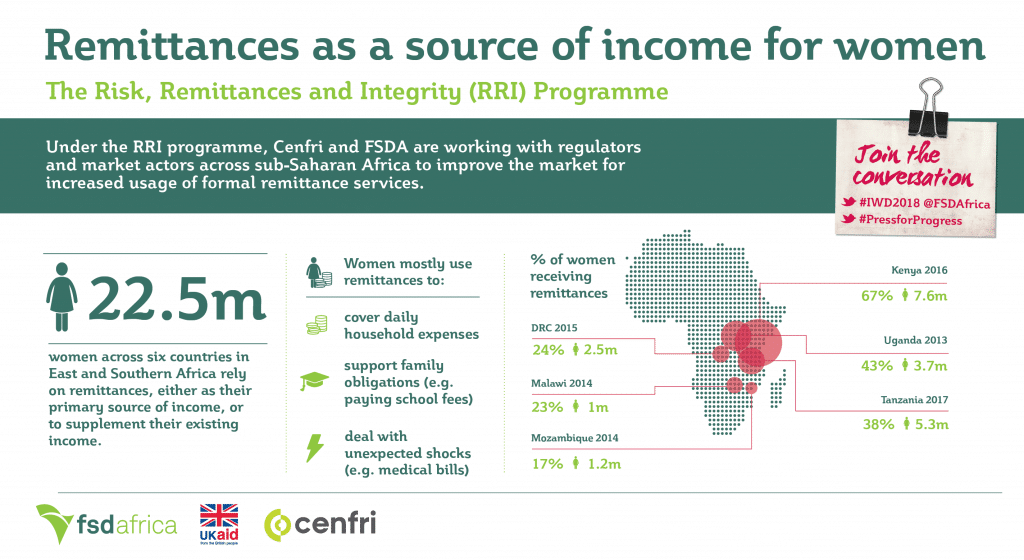

Cenfri supports financial inclusion and financial-sector development through facilitating better regulation and market provision of financial services through research, advisory services and capacity-building programmes. FSD Africa and Cenfri have partnered on the Risk, Remittances and Integrity (RRI) programme which seeks to strengthen the integrity and risk management role of the financial sector and to facilitate remittance flows within and into the continent.

With respect to remittances, research conducted by Cenfri indicates that remittances are an important source of income for women in sub-Saharan Africa. They are used to meet monthly expenses, deal with unexpected shocks, and support family obligations (e.g. paying school fees).,

Through our #PressforProgress campaign, we are proud to share information about our partnerships that are supporting women’s economic empowerment in a variety of ways.

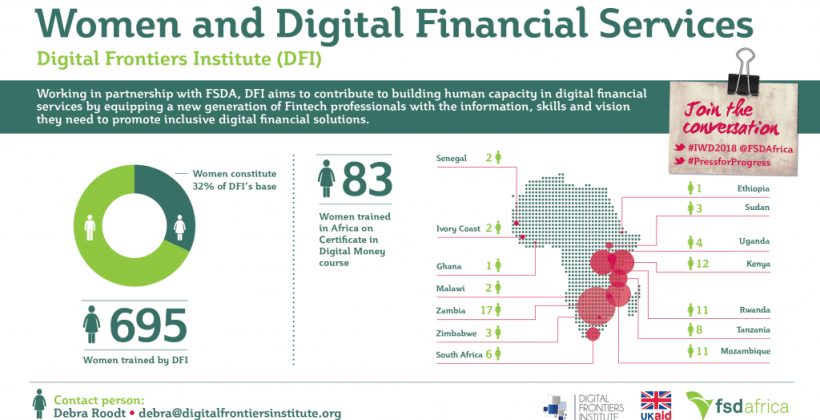

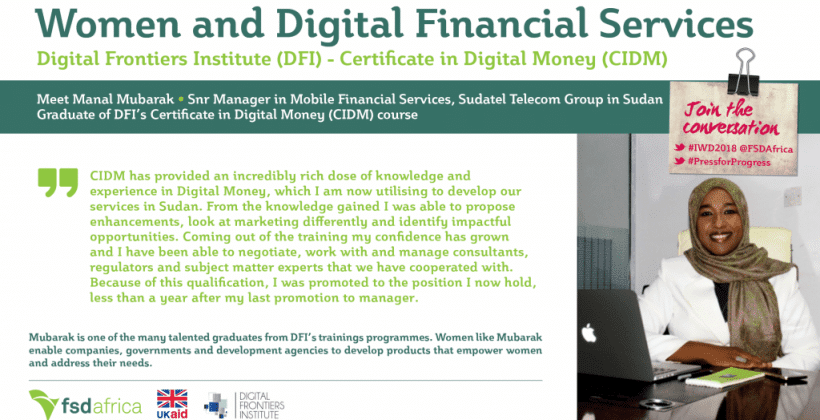

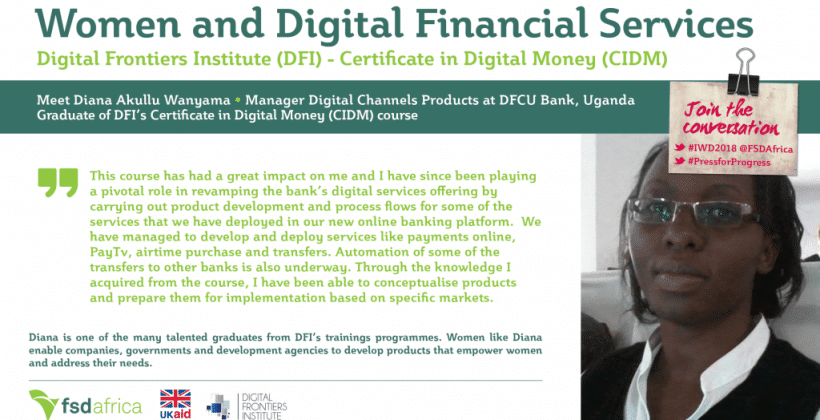

The Digital Frontiers Institute is a one-of-a-kind institution that is building human capacity in digital financial services by equipping a new generation of fintech professionals with the information, skills and vision they need to deliver and guide society towards inclusive digital financial solutions. DFI recognises the under-representation of women in leadership roles in digital financial services and fintech as well as the general lack of financial inclusion for women across the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Through support from FSD Africa and other partners, DFI is addressing these issues by equipping women with the necessary qualifications and training to develop digital financial services and products that sustainably include them and that, in turn, allow women actively participate in the economy.,

FSD Africa commissioned BFA to undertake an in-dept post-issuance survey of the first government bond sold exclusively via mobile based which provided key insights and recommendations.

This National Treasury led market development initiative to distribute government securities through mobile phones is one of the most innovative globally. Although the first pilot and launch did not achieve the desired outcome, the survey aims to enhance and guide the subsequent issuances of M-Akiba.

FSD Africa identified M-AKIBA as an opportunity to learn about an innovative tool which could enable the broadening and deepening of inclusive financial markets. The study identified successes and challenges that M-Akiba experienced.

This innovative bond aims to broaden the sources of borrowing beyond banks and other financial institutions to retail investors. The minimum subscription is less than $30 with an interest rate of 10% disbursed every six months over mobile money, at a three-year tenor.

The survey highlights the possibility for replication of this pilot issuance and explores other possible approaches for the mass distribution of securities.

The product was developed by the government in collaboration with Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE), the Central Depository Settlement Corporation (CDSC), Mobile Network Operators (MNO), and the Kenya Association of Stockbrokers & Investment Banks (KASIB).

In early November, FSD Africa brought two worlds together for the first time: taking five prominent financial service providers (FSPs) to Gihembe Refugee Camp in Rwanda to participate in a ‘Financial Product Design Sprint’ in partnership with UNHCR, Government of Rwanda, and Access to Finance Rwanda (AFR). We were also joined by a member of UNHCR from Geneva, the International Finance Corporation and FSD Uganda.

Earlier that week, FSD Africa and BFA presented research on ‘Refugees & Their Money’ to over 20 FSPs in Kigali – highlighting the business case for financial products focused towards refugees (you can find a short summary found here). Philip Kakuru, from Tigo, said ‘With the limited access of the refugees, there was little to know about them, but the sprint design opened our eyes’. These FSPs, along with any others, now have an opportunity to win one of our four £10,000 grants in our Innovation Competition – Financial Services for Refugees in Rwanda.

To read more about the wider FSDA approach to refugee finance, take a look at last month’s blog here.

The next day, the five FSPs, chosen through an open competition, began the Financial Product Design Sprint. The FSPs were a diverse group representing MMOs, MNOs, MFI and banks: MobiCash, Equity Bank, Vision Fund, Tigo and Commercial Bank for Africa. This three-day event hoped to challenge misconceptions about refugees, their potential and FSPs to consider a refugee product seriously. The first day began with an in-depth presentation of BFA’s research and details regarding the structure of refugee camps. This was followed by product brainstorming with each FSP, before narrowing down to a select two or three ideas which were fleshed out.

On the second day, these FSPs were taken to Gihembe Refugee Camp, a camp with a population of around 12,000 refugees from DRC and located only an hour drive from Kigali. Here, each FSP had the opportunity to speak to at least two refugees and over the course of two hours get a better feel for their financial lives. For most, this was their first time interacting with refugees and particularly in a refugee camp. As one FSP noted ‘With this segment, there is a lot to offer and learn from them’. This was followed by further prototyping of the FSP’s idea and customising their product to the needs of refugees.

The final day offered an opportunity to return to the camp and with initial prototypes, in the form of a drawing, poster or app, get direct customer feedback. This proved particularly helpful for many FSPs to refine their product. As Peter Kawumi, from FSD Uganda, said ‘Through the design sprint’s customer interaction iterations, misconceptions about the refugees’ technology literacy, economic independence and financial ambition were debunked.’

The first ‘Financial Product Design Sprint’ was well received by all FSPs and there is also potential for replication in Uganda, with FSD Uganda, and as Vishal Patel from the IFC said ‘helped inform IFC’s work in Kenya in Kakuma refugee camp and town.’

Learning from risk taking

Working with banks and beneficiaries in this way is new to FSD Africa. It builds on the FinDisrupt model, pioneered by our sister organistion – FSD Tanzania. We learned a lot, especially on the value of bringing the refugee voice into FSD Africa planning and FSP business casing. The type of discussion it generates, out of the office environment, created momentum that would otherwise never have been achieved.

To read more about the wider FSDA approach to refugee finance, take a look at last month’s blog here.

Between 1-3 November 2017, FSD Africa brought two worlds together for the first time. Working with UNHCR, Government of Rwanda, and Access to Finance Rwanda (AFR), we took decision-makers from the banking community into Gihembe Refugee Campin Rwanda to participate in a ‘Financial Product Design Sprint.’

Refugees and other displaced populations are not an obvious place for FSD Africa to be working. We are a financial sector development programme, focused on developing markets and commercially viable financial systems over the medium to long term. Refugees, in much of the popular narrative, are transient, risky and poor – not a client group that a bank would typically target. So how do you foster private sector interest in refugees as customers?

The role of markets in humanitarian crises is not a new subject. Amartya Sen wrote Development as Freedom (1999) almost twenty years ago, making the argument that famines and other crises are caused by a complex web of economic, political and social forces, not just a disruption to food supply. If we focus on one cause of a humanitarian crisis, we’ll miss the underlying challenges that allowed it to happen. The failure of markets is often a critical factor in creating a crisis, and the development of functioning markets are vital for any long-term solution. We think that financial markets play a key role in a long-term, sustainable response effort, by easing transactions, supporting safety nets, helping to manage risk and channeling credit to those who can use it productively.

Sen was writing about famines in the late 1990s, when the total number of people of concern (refugees, IDPs and other forcibly displaced people) in the world had plateaued at around 20 million. Today, this number is 67 million, and rising. There are more forcibly displaced people in Sub-Saharan Africa than there were worldwide in 1999, and almost half of these (9.8 million people) live in countries where the FSD Network has a presence. So if we are on the ground, and accept that markets (including financial markets) have a role to play, we have a strong imperative to respond.

But how? Bankers are profit-driven and risk-taking is generally disincentivised by regulatory frameworks. How can we, as the development sector, help them to build a viable business case for serving refugees?

We’re new to this. So, a test-and-learn approach makes sense. But, so far, some important themes have emerged that are guiding our work:

The current crises of displaced populations such as those in Rwanda, Uganda, Nigeria and DR Congo are going to be long and complex, and solutions need to take into account this complexity. Financial markets can play a small but critical role in the overall picture, and for that to happen, we need to get bankers interested in refugees – as incongruous as those two worlds ma

M-Shwari (meaning ‘calm’ in Kiswahili) is a combined savings and loans product launched through a collaboration between the Commercial Bank of Africa (CBA) and Safaricom. The M-Shwari account is issued by CBA but must be linked to an M-Pesa mobile money account provided by Safaricom. The only way to deposit into, or withdraw from, M-Shwari is via the M-Pesa wallet.

M-Shwari aims to deepen and diversify the consumption and income benefits of M-Pesa by providing clients with a facility to save and by offering credit beyond a user’s networks of family and friends. Surveys of M-Shwari users confirm that they mainly save and borrow to manage fluctuations in their cash flow and to cope with unexpected needs.

M-Shwari was launched in January 2013 and by the end of 2014 it boasted 9.2 million savings accounts (representing 7.2 million individual customers) and had disbursed 20.6 million in loans to 2.8 million borrowers. In 2013, only 19% of M-Shwari users were below the national poverty line; tased to 30% by the end of 2014. It can be expected that the proportion of poorer users will grow over time, as usage amongst higher income groups approaches saturation.

The key point is that as a result of M-Shwari, millions of poor Kenyans now use savings and credit services that help them manage risks, mitigate the impact of shocks and, increasingly, invest in improving their livelihoods. M-Shwari was launched in November 2012, yet its scale means it has already changed the nature of the market, and is serving as a platform for the development of innovative new products.

FSD Kenya was instrumental in bringing M-shwari to the market in Kenya. It’s approach was one of using analysis to determine actions, in particular understanding the demand side of the financial sector – the ‘poor and the money’. FSD Kenya also encouraged a first principles approach to product development (i.e. seeking to understand poor clients and then design a product that responds specifically to their needs). From this wider evelopment perspective, the sheer scale and seemingly unabated continued growth of M-Shwari and competitor products has changed the landscape of digital finance services in Kenya.

Financial inclusion has increased significantly in Kenya. During the main period of FSD Kenya’s work with savings groups, the proportion of adults using different forms of financial services increased from 41.3% in 2009 to 66.7% in 2013; a trend that continues and stands at 75.3% in 2016.

Whilst impressive, this growth has been largely restricted to payments services. More than one-third of Kenyans – more than 5 million people – continue to rely on informal sources of savings and credit. These are usually group schemes, which help families cope with short term risk and invest in their longer term aspirations. Informal group schemes are particularly relevant to women and people in rural areas.

Savings groups are self-selected groups, with up to fifty people who pool their money in a loan fund from which members can borrow. The groups are independent and self-managed; all transactions being carried out at meetings in front of all members to ensure transparency. Savings groups require formation and initial capacity building through a structured process of training and support. However, once established, it has typically been expected that most will continue to function independently, and additionally stimulate some degree of copying by others.

A considerable amount of evidence emerging from several countries, including Kenya, prompted FSD Kenya to support savings groups. This evidence showed that sustainability of formed and trained groups was encouraging (i.e. they continued to reform after shareout), as were signs of copying (i.e. new groups being established).

A key question that FSD Kenya sought to answer was the “extent to which SG programmes are increasing financial inclusion, by bringing one basic service to people who previously had none, or enriching financial inclusion, by bringing an additional service to people who may also use mobile transfer services or a SACCO, or a bank account.

The higher percentage of informal usage among SG members, compared to non-members, coupled with the lower percentage of exclusion among SG members, strongly suggests that the SGs brought financial services to significant numbers of people who previously had none. SGs may also have a financial literacy effect inducing members to use other services”

Tomorrow, President Obama will come home to Kenya. He is likely to get calls from relatives asking for him to ‘chip in’. He will be expecting them. These types of calls are not uncommon in Kenya.

Only the other day, I got a text message while I was a work: “Uncle Matata is very sick and is seeing a doctor. The money we had budgeted is not enough. Can you help?” In Kenya, social obligations dictate that you ‘chip in’.

For me, it was just an ordinary day in the office and so I had left my debit card at home. My car had enough fuel to last three days so I took just a little cash for lunch. When I got the message, I checked”https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M-Pesa”>M-Pesa e-wallet and found it had half of the amount being asked for. So I sent a text back asking them to hold on as I waited for my meeting to end. After the meeting I stepped out and asked a colleague if he had some money in his M-Pesa e-wallet which I could borrow and refund that evening. I was able to send the money via M-Pesa.

According to the Central Bank of Kenya there are about 124,000 mobile money agents, serving 25 million customers, who made over 900 million transactions worth over KES 2.4 trillion (around USD $24 billion). This compared to about 12 million debit cards with 18 million transactions worth only KES 108 billion (approx. USD $1.1 billion) during the same period.

A growing number of banks and other financial institutions are looking to leverage the existing digital financial service infrastructure. But many are struggling to understand the key elements of these: from strategy to product delivery as well as how to drive uptake and usage, while managing risk and fraud. They need help.

FSD Africa recognises the important role that mobile money plays in facilitating payments. We have provided financial support to MicroSave Helix Institute for Digital Finance to research, design and train digital finance professionals across Sub-Saharan Africa.

When Obama visits Kenya he is likely to get calls from relatives. Some of those might be appeals for him to play his part in building social capital of Kogelo (the village where he comes from). Others might be from African leaders urging him to cement his legacy before he leaves office. For that, he may use a USAID grant from the State Department or a communique at the end of a global summit. But for family and friends in need of a just few shillings to tide them over, he will need his M-Pesa mobile money account. Because even he is expected to chip in