As countries around the world race to combat the effects of climate change, carbon trading continues to gain traction.

Carbon trading is the buying and selling of permits of carbon credits that allow the holder to emit a certain amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (GHGs).

Financial site Investopedia defines a carbon credit as the equivalent of one tonne of carbon dioxide or any other GHGs that an organisation can emit into the atmosphere.

Essentially, companies are awarded credits to allow them to continue to pollute up to a certain limit, often on a reducing basis.

What happens when a company exceeds its limits?

While some businesses are able to cut their emissions, others are not able to do so. For some, their emissions might even increase in the course of a given period.

Those that cannot reduce their emissions are, however, allowed to continue operating, but usually at a higher cost.

In some instances, businesses are unable to exhaust their credit limits even after operating for the marked duration. These are called ‘‘surplus’’ or ‘‘excess’’ credits.

When a business is left with unutilised credits, it can sell them to other businesses. The business may also choose to keep the surplus credits for future use.

What is the difference between carbon credits and carbon offsets?

While carbon credits and carbon offsets are sometimes used interchangeably, they are different commodities with the same goal of reducing the emission of carbon and other GHGs into the atmosphere.

Carbon credits are limited to within an area and are regulated by a governing body. It is this governing body that is also responsible for creating and distributing them to companies operating within that jurisdiction.

Carbon offsets are neither created by a specific entity nor distributed by a particular body. Instead, they are traded freely on ‘‘voluntary markets.’’

Read: Northern Kenya conservancies eye pie of carbon credit billions

While carbon credits ‘‘cap’’ emissions, carbon offsets compensate an organisation for investing in carbon projects, also called green projects, that help to cut down emissions.

Carbon offset projects can be realised through activities that either reduce the emission of greenhouse gases or those that increase carbon sequestration.

Some of these activities may involve investment in renewable energy forms to displace fossil fuels that emit carbon and reforestation to increase the number of trees that serve as carbon sinks.

Does Kenya have a history of carbon trading?

This trade dates back to 2014. A group of 60,000 smallholder farmers in the Western region under the Kenya Agricultural Carbon Project (KACP) earned carbon credits for sustainable farming.

The credits had been issued worldwide under the sustainable agricultural land management (SALM) carbon accounting methodology.

The programme supported the farmers to grow crops in a productive, sustainable and climate-friendly manner.

With its forests, expansive grasslands and wetlands, Kenya is considered a rich carbon offset sink. This is expected to improve even further once the country attains its target of planting 15 billion trees in the next 10 years.

How is carbon trading regulated in Kenya?

One of the functions of the National Climate Change Action Plan under the Climate Change Act of 2016 is ‘‘to guide the country toward the achievement of low-carbon climate-resilient sustainable development.’’

It does not, however, address specifically how trading in carbon credits, as a climate change response, will be regulated in Kenya.

Environment lawyer Stella Ojango acknowledges the gaps, noting that Kenya’s limited regulatory framework and absence of requisite laws make carbon trading in the country an almost opaque undertaking.

‘‘We have the Climate Change Act of 2016, but it does not address carbon trading sufficiently. We need to amend that Act so that we can introduce regulations for trading carbon. Enriching our laws will help to regularise this business.’’ Ojango says.

Last year, the Nairobi International Finance Centre (NIFC) said Kenya lacks a clear framework for buying and selling carbon credits locally.

The body noted that this unregulated sale of carbon credits costs the country billions of shillings in unrealised revenues.

The organisation is planning to establish a carbon trading exchange in the country to allow small-scale trade-in credits.

‘‘We need to have in place mechanisms that measure how much carbon is being absorbed through reforestation. This way, we will have created a market. Regulating the pricing aspect will then become easier,’’ Ojango adds.

How are carbon markets regulated elsewhere?

Kenya is not alone in lacking proper regulation for carbon trading. Most of the carbon credit markets in the developing world are unregulated by law. There are no agreed prices for carbon credits.

Plans are underway to establish a global carbon credit and carbon offset trading market. This was agreed on by negotiators at COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. Carbon credits also exist within markets with Cap & Trade regulations.

Who is trading in carbon credits in Kenya?

A number of businesses and organisations are already making money from either carbon credits or carbon offset programmes.

In Northern Kenya, conservancies are increasingly moving away from tourism as their mainstay to now invest in carbon projects as a source of revenue.

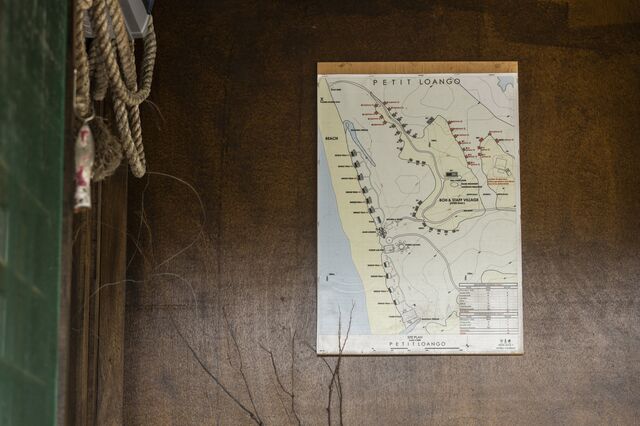

Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT), for instance, has put 4.7 million acres of grassland under a carbon project.

NRT is a group of 39 marine and land conservancies that cover, among other counties, Laikipia, Samburu, Tana River and Lamu. Out of these, 14 are under the project.

The Northern Rangelands Carbon Project will focus exclusively on the removal of carbon from the soil, with a target of 50 million tonnes of CO2 in 30 years. This effectively makes it one of the few projects of this scale in the market globally.

Last year, Kenya Forest Service (KFS) signed a deal with global audit firm BDO that would see the government agency earn millions of shillings for offsetting carbon dioxide.

According to the deal, KFS will rake in $15 (Sh1868) for every tonne of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere by government forests.

In villages in coastal Kenya, communities living near the sea are selling ‘‘hewa kaa’’ to international corporations to help them reduce their carbon emissions.

This carbon project is promoting the conservation and sustainable use of mangrove resources by the villagers.

Controversy of trade

While widely adopted around the world today, carbon credits still divide opinion. Those in support say carbon trading is a ‘‘measurable and verifiable’’ emissions reduction strategy through climate projects.

Those opposed to carbon offsets call the trade ‘‘a scammer’s dream scheme’’ and the next big thing in greenwashing.

Climate change advocacy organisation Greenpeace dismisses carbon offsets as a bookkeeping trick ‘‘intended to obscure climate-wrecking emissions.’’

Read original article