These trees are Gabon’s superstars. They absorb and store millions of tons of earth-warming carbon dioxide each year, a critical function for the global fight against climate change. They also fuel the country’s timber industry, a major focus of economic development during the past decade.

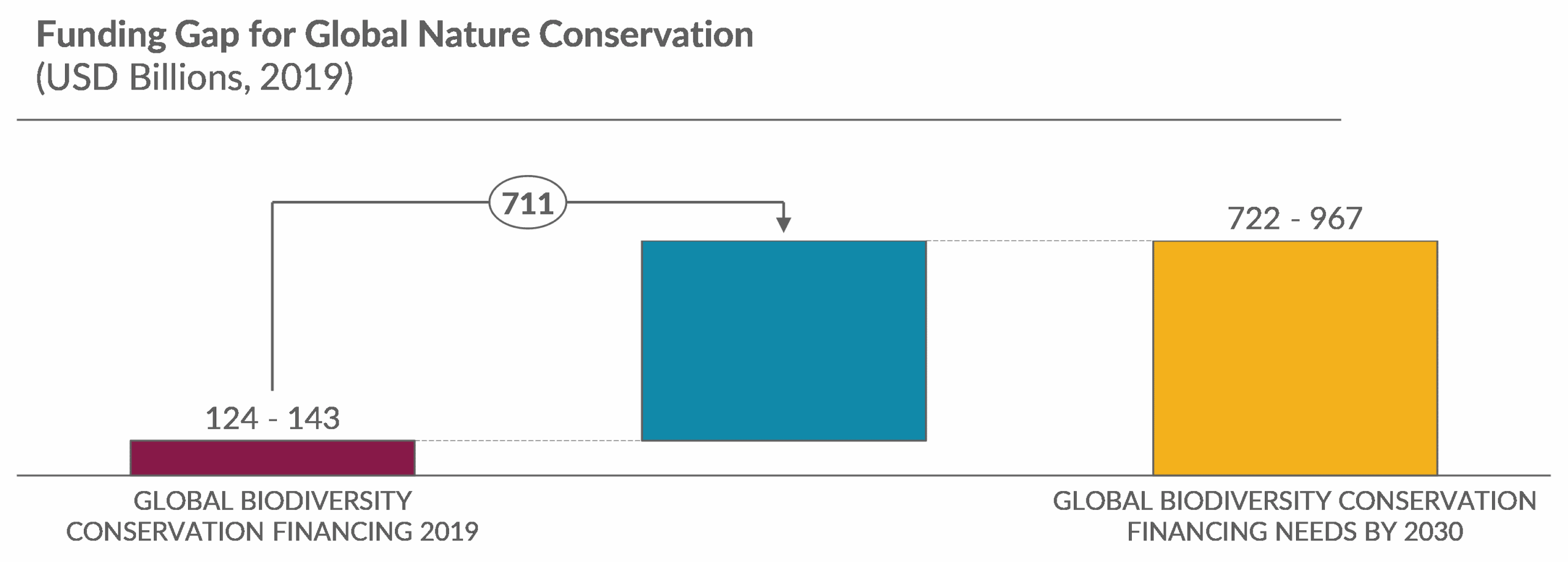

In today’s financial markets, Gabon’s trees are worth more dead than alive. Despite the billions pledged worldwide to fight climate change, little has been distributed as compensation for the global benefit that trees provide. In 2021, Gabon received its first payment for reducing forest-related emissions—$17 million via the Central African Forest Initiative.

The timber industry, on the other hand, contributes about $1 billion to Gabon’s annual gross domestic product. It could be a great deal more. Unlike some of its neighbors, the country strictly limits logging, palm oil production and other activities that lead to forest destruction; it’s suffered less than 1% forest loss since 1990, compared with about 14% for continental Africa.

Now that oil production, the country’s primary source of revenue, is dwindling, leaders are reevaluating the money-making potential of the forests. Opening more land to timber companies is one option, but for now Gabon’s environmentally minded government is more interested in keeping the trees alive—if the international financial markets can make it worthwhile.

The best avenue for that, Gabon says, is the $2 billion-and-growing market for “carbon offsets.” That’s traditionally been limited to those who can document improvement on past environmental practices, not those who, like Gabon, never wrecked their forests in the first place. That’s because for a carbon offset to fulfill its function of compensating for its buyer’s emissions, it needs to have financed something that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. But in Gabon, forest protection has been happening anyway.

Still, Gabon insists it should be compensated for the air-purifying service its trees provide. Otherwise, it hints, its commitment to forest preservation may take a backseat to more traditional economic development. In its recent national action plan under the Paris Agreement, the global climate pact, the country says it plans to remain a “net-carbon absorber”—if it gets access to international finance through a carbon market.

“There is no financial instrument to support Gabon to continue to offer this critical ecosystem service,” Akim Daouda, the chief executive officer of Gabon’s $1.9 billion sovereign wealth fund, said in an interview during a recent trip to London. “Can we monetize the forest and keep it for the rest of the planet? Or do we need to find a way to respond to the needs of our population?”

Gabon’s per capita GDP is the highest on the continent, but there’s little evidence of wealth past or present in Nyanga. One of the few local health centers lacks running water, exposed wires poke out of the walls, and bare mattresses cover four, cast-iron bedframes.

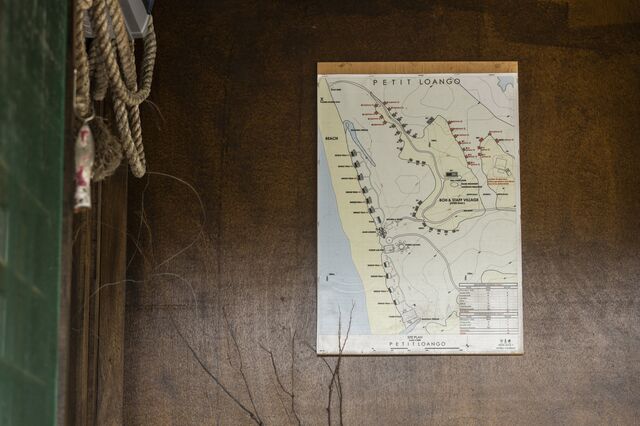

The province is home to a 100,000 hectare (247,000 acre) cattle ranch, part of the Grande Mayumba project. A flagship of Gabon’s “sustainable development” efforts and backed by investments from the family offices of the Westons, Fricks and Sarikhanis, Grande Mayumba’s plans include logging, cattle farming and eco-tourism, as well as an area 37 times the size of Manhattan set aside for conservation.

The ranch raises N’Dama, a small chestnut-colored breed of indigenous beef cattle that tolerate tsetse flies and the sleeping sickness they carry. The 4,000-strong herd will grow and eventually roam alongside wild buffalo and antelope. The free-range model will minimize harm to the savannah ecosystem, and careful grasslands management could boost the soil’s carbon stock, according to Africa Conservation Development Corp., Grande Mayumba’s parent company.

The ranch isn’t profitable yet. So far, only Grande Mayumba’s logging operation is fully operational. The rest has moved far more slowly. To raise the money needed to really get the project off the ground, ACDG will need to issue and sell carbon credits.

The forest-based carbon offsets on the market today tend to be based on projects that seek to avoid emissions or increase carbon storage. Limiting deforestation usually qualifies; so could planting trees. Developers usually calculate how the forests fared under their control compared with a historical baseline, then sell the difference in units of extra tons of carbon removed or avoided as offsets.

But because Gabon already has stringent restrictions on logging and there’s little deforestation to speak of, ACDG has had to take a different approach. Based on trends in more than a dozen once-highly forested countries, it contends there’s an imminent threat to the trees in Nyanga. Pending government approval, ACDG will sell credits based on how Grande Mayumba’s activities avert that hypothetical future destruction.

“There will be development in the Grande Mayumba area over time,” said Rob Morley, science and environmental planning director at ACDG. “This will either be unsustainable, unplanned and that will lead to a large amount of forest loss, or it will be planned.”

On the ground, the threat feels distant. About the size of Israel, the province is Gabon’s poorest, with just three paved roads, two hospitals and few public services. Residents have gone looking for better opportunities in Gabon’s main cities, leaving a population of around 53,000.

The Grande Mayumba project says it will generate as many as 4,000 jobs, mirroring President Ali Bongo’s Gabon Émergent, the country’s three-pillar development strategy based on industry, the environment and a services economy. Most will work in forestry or ranching, but a handful will staff a luxury ecolodge under construction in neighboring Ogooué-Maritime province. For $2,000 per night or so, well-heeled tourists will be able to see hippos frolic in the surf and ghost crabs dash in and out of the waves.

When ACDG figures out how to stabilize a runway on the sandy soils, guests will be able to access the lodge by plane. Until then, it’s a half-day journey from the nearest main town, by car, river barge and speedboat. The last leg is by quadbike along a strip of beach frequented by buffalo and the odd elephant, tide permitting.

In its original plans, Grande Mayumba expected its model to generate as many as 200 million credits over the next 25 years. At today’s prices, that would be worth about $2 billion, according to data provider Allied Offsets, roughly equal to Gabon’s sovereign wealth fund.

So far that’s yet to materialize. The British bank Standard Chartered Plc and Swiss trading firm Vitol SA have expressed interest, but neither have culminated in a deal. Investors are getting antsy.

Josh Ponte, a former gorilla researcher and special adviser to the President of Gabon and now an ACDG director, bemoaned the delay in carbon-credit revenue.

“The carbon play was a core incentive,” he said, sitting on a rudimentary platform that will eventually be a dining room. Other than some staff lodging, there’s little more to see. “But there’s since been a reality check on the timeline of the carbon credits, how they’ll work, and how they’ll fit with government strategy. It’s really tiring our investors.”

Gabon Vert, the environmental pillar of the Bongo administration’s development plan, frames both its deal with ACDG and the country’s plans to issue its own, sovereign carbon offsets. Gabon’s offering will rely on different math. It plans to tally the CO2 its trees suck out of the atmosphere, subtract its own emissions, and sell the difference to other, more polluting countries as “net sequestration” credits.

Anyone can issue carbon credits, and anyone can buy them. Most developers use third-party verification bodies to vouch for the quality of their offerings. Gabon doesn’t plan to do so. Fledgling exchanges are also trying to streamline trade, but for now, over-the-counter, bilateral deals are the most common.

It’s not clear the markets will bite. Gabon’s plans have been met with caution. It’s yet to sell some 90 million credits it already generated for past carbon absorption using an established albeit contested approach.

“It always makes me nervous when people say they’re going to roll out their own methodology,” said Danny Cullenward, policy director at nonprofit research group CarbonPlan. “It’s really easy to manipulate the methodology intentionally or incidentally to produce outcomes that are less credible or inconsistent with other key points of data.”

Methodology aside, political uncertainty hangs over Gabon. The fate of Gabon Vert may depend on the outcome of the presidential election later this year.

Though a member of the Bongo family has led Gabon for the past 56 years, the current presidency is under a cloud. Ali Bongo won his most recent election by fewer than 10,000 votes, triggering charges of ballot-rigging and days of violent protest. A 2019 coup attempt failed, and Bongo has had a stroke.

Ahead of this year’s presidential election, the government has embarked on an aggressive green diplomacy push. In February, a delegation joined the UK’s environment ministry and King Charles III to chat conservation. This week, Emmanuel Macron will attend a “One Forest” summit in Libreville, the first time a French president has visited the country in about a decade.

The Grande Mayumba project was already halted once, in 2015, when Gabon’s then-oil minister gave the site of a proposed port to a Moroccan company, despite an agreement that assigned it to ACDG. Development stalled until the dispute was resolved in 2018.

“If the president were to change, I’m not convinced that the model has got deep enough roots yet to be fully sustainable,” said Lee White, environment minister in Bongo’s government. The project also is facing a groundswell of opposition from local communities and NGOs. A grassroots campaign called “No to Grande Mayumba” calls for the suspension of the plan, saying restrictions on access to resources threaten the custom and livelihoods of subsistence farmers who haven’t been adequately consulted.

“There’s sacred forest here and the local population should be consulted on what can and can’t be cut down,” said Nicole Nouhando, governor of Nyanga province who’s broadly supportive of ACDG’s plans.

ACDG has had its own turmoil. Alan Bernstein, the South African safari entrepreneur who founded the company, left after a falling-out with its biggest investors. ACDG says he no longer holds stock in the group; Bernstein says he is seeking compensation after an initial court settlement in January.

For now, Gabon and ACDG are pushing ahead. In the absence of oversight, their success depends less on whether the credits help avert climate change and more on whether and how much a buyer will pay.

In December, US oil company Hess Corp. sealed the first purchase agreement for a similar kind of “high forest, low deforestation” credits with Guyana. Earlier in the year, the International Civil Aviation Organization said those credits could be used by airlines to offset their emissions. Experts have cautioned the credits will fail to serve their purpose.

If ACDG or Gabon can make a deal, it will add fuel to the efforts of other rainforest nations across the world’s tropical belt.

It could also pit the government at odds with the private sector. Gabon is one of a handful of countries with agreements to generate and trade their own carbon credits under a new carbon market run by the United Nations, according to Trove Research Ltd., a carbon analytics company. Last year, White castigated TotalEnergies over a new forest-based credits plan in Gabon. “They don’t have the rights” to that carbon, he said.

ACDG retains the government’s support. The success of the Grande Mayumba project would encourage “forest countries to continue preserving their forests,” said Daouda of Gabon’s sovereign wealth fund, which will market the country’s carbon credits. For him, it would answer the country’s big question in the affirmative: “It would mean that today, the world is recognizing that a living tree has higher value than a dead one.” —With Akshat Rathi and Ben Elgin

Read original article