It is 10 months this week since Kenya – where UK aid-funded FSD Africa has its headquarters – confirmed its first case of coronavirus (COVID-19). Today, I want to take stock of our wide-ranging work over this unprecedented 10-month period, while looking ahead to chart FSD Africa’s evolving contribution to COVID-19 response efforts – from providing liquidity to ensure households and businesses have access to credit, to supporting the most vulnerable in fragile communities and states preparing Africa’s financial markets to bounce back better – and becoming more resilient, more inclusive and greener in a post-pandemic world.

Like many companies and organisations around the world, we have been working from home and not travelling. However, this has not interrupted our efforts to design and deliver programmes to help Africa’s poorest households and communities.

From the beginning of the crisis, FSD Africa has focused its response on what it does best: strengthening financial markets so that they can better serve poor and vulnerable people.

Our efforts to respond to the effects of COVID-19 are therefore concentrated around three pillars:

First – we’re providing emergency liquidity.

Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are the engine of growth in African economies. They drive innovation and create employment, especially among the pivotal youth segment of the labour force. MSMEs have had their consumption patterns disrupted and incomes put at risk due to the economic slowdown. COMESA’s survey found that 80% of MSMEs have been severely or very severely affected by the pandemic, citing the lack of operational cash flow as a major driver.

We are responding by making strategic investments in financial firms and funds that channel credit to these MSMEs. For example, FSD Africa Investments has invested in BlueOrchard‘s COVID-19 Emerging and Frontier Markets MSME Support Fund. BlueOrchard is a specialised impact investment manager which provides microfinance debt financing to more than 180 financial institutions in over 50 emerging markets. FSD Africa is participating in the first loss tranche of the new fund and, in doing so, has been instrumental in crowding in other investors such as the UK’s CDC Group plc and JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) to get to a first close of USD 100 million. This fund is directly helping to ensure households and businesses have access to the credit they need to preserve incomes, and jobs, and, later, to grow and thrive – a significant catalyst for building back better.

We are also investing in Lendable, the first debt crowdfunding platform designed specifically to finance African non-bank lenders (alternative lenders) that use digital technology to provide new financial solutions for MSMEs. We are very excited about this investment as it not only responds to the impact of COVID–19 but it also accelerates the digitisation of MSME finance in Africa, which in turn lowers transaction costs and expands access – trends that will also help drive inclusive MSME-led growth in the long run. By increasing the access of alt-lenders in the African market to affordable capital, the most competitive and innovative of these ‘disruptors’ will be well-positioned to grow and help meet the financing needs of MSME customers at transformational scale. By 2021, Lendable aims to provide $706 million in liquidity to 75 alternative lenders in 15 countries. As the first marketplace lender of its kind in Africa with a young (but growing) track record of securitized deals, Lendable is laying the groundwork for new and sustainable capital markets investment flows to credit markets in Africa. At a time when COVID-19 is prompting a surge in sovereign borrowing in domestic banking markets that may crowd out traditional MSME credit flows, this diversification of the lender landscape is timely and necessary.

Second, we’re responding with tailored interventions for fragile communities and vulnerable people.

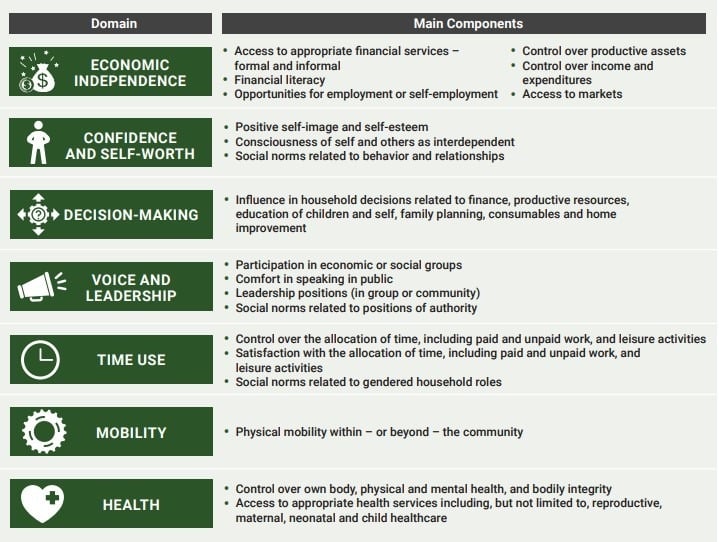

Fragile communities within the African continent are faced by several obstacles to flattening the COVID-19 curve. The lockdowns across the continent have resulted in business and school closures, market disruptions and job losses. This has led to income losses for a significant number of low-income and informal workers in countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya, and Nigeria. According to a survey conducted by Performance Monitoring for Action in DRC, Burkina Faso, Kenya, and Nigeria, the effects of the pandemic have also particularly affected women who have become apprehensive about accessing healthcare as their new immediate priority is feeding their families. A recent study conducted by UN-WIDER estimates that the number of people living in extreme poverty (under USD 1.9 a day) particularly in the Middle East and North African region and the Sub-Saharan regions could rise to poverty levels similar to those recorded 30 years ago.

Our existing programmes are all adapting and adjusting to the challenges presented by COVID-19. Our Financial Inclusion for Refugees Project, in collaboration with FSD Uganda and BFA Global, supports the development of financial products and services offered by Equity Bank Uganda, Vision Fund Uganda and the Rural Finance Initiative. In response to the pandemic, FSD Africa is encouraging digital payments, assisted by the reduction in mobile money fees in the region, as the pandemic redoubles the importance of non-cash alternatives in high population density settings. FSD Africa, in partnership with GiveDirectly and Mastercard Foundation, also continues to disburse cash transfers to young entrepreneurs in Mathare, a large slum in Nairobi, supporting 1,000 beneficiaries, all young people, trying to get ahead in informal business, to invest in their businesses, pay off existing debts, fund education and utilise technology to advance their businesses. This Youth Enterprise Grants programme started long before COVID-19 but has proved itself to be an effective delivery model that others have emulated specifically in response to the pandemic.

In October, we launched a landmark $6.5 million fund set up between the UK and Germany in collaboration with the Government of Ethiopia to save thousands of jobs in Ethiopia’s textile and garments industry. The development of textile and garment factories in Ethiopia has been transformational to the country’s nascent industrialisation. Yet this progress is under threat by COVID-19 – especially as retailers have cancelled hundreds of millions of dollars worth of orders across the global garment industry. Already, 13 textile firms have stopped operating due to low demand. Preliminary estimates suggest that 1.4 million jobs are under threat although this figure could be as high as 2.5 million. Through the Jobs Protection Facility, factories in Ethiopia’s industrial parks can apply for wage subsidies – similar to the furlough schemes operating in many countries including the UK and Germany – as well as incentives to reward businesses that are able to adapt in response to COVID-19.

Finally, we have a unique opportunity to ensure the recovery is sustainable, inclusive and green.

The pandemic has caused severe damage to African economies, but crises throw up new possibilities and can be a catalyst for change. This theme spans all areas of FSD Africa’s work – capital markets, insurance markets, remittances, agency banking, green bonds and beyond into new areas such as healthcare, agriculture, eco-tourism and energy. As an example, in our recent publication “Never waste a crisis – how sub-Saharan African insurers are being affected by, and are responding to, COVID-19” we find that while the pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing weaknesses in the insurance sector in SSA, it also provides an opportunity for insurers and regulators to become better equipped to embrace innovation and deepen their insurance markets – an opportunity we want to capitalise on. In addition, we are proactively assisting governments to innovate. For example, we are supporting the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in Nigeria to modernise and transform its ICT systems – demonstrating that technology has role to play even for regulatory agencies in making them more accessible, efficient and resilient.

Green finance has become a major priority for us. Building on long-standing work in the development of green bond markets especially in Kenya and Nigeria, FSD Africa now has major workstreams in green finance across its entire programme. In partnership with Cambridge University, the Eastern & Southern African Management Institute (ESAMI) and the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), we announced a major new green finance training programme which will help policymakers and the private sector alike secure investment in green projects across the continent. Whether the focus is on reducing emissions or resilience, urban spaces or the natural environment, green finance is the cross-cutting catalyst for change and FSD Africa has a major role to play in the run-up to COP26 and beyond, working with excellent partners to power a green recovery in SSA from COVID-19.

This short round up touches on just a fraction of the work the FSD Africa is doing. I look forward to sharing further updates in the weeks and months to come. For now, I personally want to thank the UK government for its constant support and encouragement in these very difficult times; our implementing partners for their excellent delivery and willingness to adapt; and, especially, to all the FSD Africa team for their tireless efforts to design and manage these catalytic programmes at speed. For more information, please get in touch.