In March 2020 when the first wave of Covid-19 hit, countries around the world introduced stringent public health measures. Kenya was no exception. Schools were shut, government and office workers were encouraged to work at home, markets were closed, curfews were introduced and movement in and out of Nairobi was banned.

Although these measures reduced the spread of the virus, their economic impact was swift and damaging. Millions of people’s livelihoods disappeared overnight. For those working in the informal sector in Kenya, which accounts for up to 77% of all employment,[1] days without income quickly became days without food. As the lockdown continued, the World Bank and others predicted dire consequences for long-term economic growth and poverty reduction targets.

Today, although the Covid-19 and macro-economic outlooks remain unclear, recent research undertaken by FSD Africa in Mathare, one of Nairobi’s largest slums, indicates that Covid is only the tip of the iceberg. The pandemic is potentially diverting attention away from the underlying drivers that make or break the livelihoods of Mathare’s inhabitants.

The Youth Enterprise Grant project

Over the last two years, FSD Africa has been studying over 1,000 youth living in Mathare as part of the Youth Enterprise Grant project. Starting at the end of 2018, young people aged 18–35 were given a smartphone and an enterprise grant totalling $1,200. Half of the participants received the grant in three lump-sum payments at the beginning of the programme, while the other half received a monthly stif $50 over two years.

The project was implemented by cash transfer specialists GiveDirectly, with funding from the MasterCard Foundation, FSD Africa and the Google Impact Challenge Fund. Ongoing research over the period sought to ascertain how the youth used the money and the phone to improve their lives and livelihoods.

Covid-19 strikes

One year into the project, the research showed several promising findings, such as the proportion of youth describing themselves as ‘self-employed’ – running their own business – increasing from 34% to 67%. Data also showed that a third of all transfers were being spent on new or existing business investments, with a further 13% of transfers spent on education. There was practically no evidence that funds were being misused.

But during the second year of the project, the Covid-19 pandemic struck. Researchers feared its impact would undermine the business investments and other gains reported up to that point. It was felt that the lump sum recipients, whose grant payments had finished approximately one year before, would be particularly affected.

The results of the project were therefore awaited with some caution. This included the responses to post-payment telephone surveys with monthly recipients, a final telephone survey of all YEG recipients and several longitudinal case studies.

But these findings, shortly to be releasedAfrica in the project’s final report, provide a more nuanced picture than expected of the economic impact of Covid-19 on micro-business and survival in the Nairobi slums.

The mixed impact of Covid

There is no doubt that lockdown affected the livelihoods of the YEG youth. Teresia, age 29, explained:

“Before Covid, I was working several days a week cleaning in the house of a Chinese businessman. When lockdown came he told me to stay away as he didn’t want people coming into his house. I didn’t get paid when I didn’t work.”

Many others reported similar stories, and in the endline survey, carried out in January 2021, 90% of respondents said their income had decreased substantially during lockdown.

Nonetheless, the broader research findings indicate that the impact of Covid-19 as a whole was temporary, and limited largely to the initial lockdown period. Analysis of other questions posed in the endline survey shows that most respondents, including those that received lump-sum payments nearly a year before pandemic, emerged in a better financial situation than at the beginning of the project.

Micro-entrepreneurs were resilient

All youth reported sustained positive perceptions of their financial situation at the end of the project compared with the start, with a marked increase in those feeling they could meet all their daily needs on most days.

The shift to self-employmalso sustained, with the majority of youth (79%) describing themselves as self-employed and 68% describing self-employment as their main source of income. The figures show little difference between lump sum and monthly payment recipients, indicating that business investments made with transfers at the beginning of the project survived.

Interviews held after lockdown revealed that although most participants experienced reduced or suspended business activity and income, Covid-19 had not caused any participant’s business to fail outright. While five of the nine interviewees said their businesses were directly affected by Covid, they tended to describe them as being ‘on hold’ during lockdown, rather than ‘failed’.

All felt these business ventures were restarting as demand picked up. This was especially true of skills-based businesses, like hairdressing, construction and cleaning, which are relatively easy to restart once demand increases.

A couple of businesses even grew during the lockdown. One yout in a modem to sell wifi connections to households in his area, which increased in demand as more people (including school children) were forced to work at home.

Covid was one issue among many

All of this challenged researchers’ initial concern that the Covid-19 crisis would be such a significant shock it would wipe out any economic gains arising from the project. Instead, the YEG research found that although Covid-19 was a major shock, its impact in Mathare was no greater than that of many other issues affecting micro-business operators.

Four interviewees, for example, reported businesses that had failed for reasons unrelated to Covid. Only one of these was due to poor business skills. The other three reflected the highly precarious nature of operating a business in informal settlements: they were due to livestock disease, police raids and medical expenses.

The challenges of running a micro-business

These issues echo comments made in focus groups when participants were asked about the chlenges of running their businesses. Rather than emphasising lack of skills, they cited a litany of other obstacles in operating in a place like Mathare:

“So I bought hair braids with the money. After that, it’s like thieves realized we have been given the money and they came and stole from me. They took everything.”

“You know we don’t have title deeds here so we are just risking, anytime we can be kicked out and I lose my rentals. Also, because we hear about slum upgrading so we must feel insecure about our business.”

“Personally, I have a small kiosk, there are people who come to me pretending they are city askaris but they just want money, the chief, people just wanting to disturb you and your business.”

In several cases, medical costs and funeral expenses had wiped out participants’ savings or undermined their ability to keep businesses afloat. Other challenges related to the unreliability of basic services:

“Challenges are like: when we don’t havey; you find that no money will come in [to the bio-block] that day. Also, when there is no power our video business suffers.”

Issues around crime, theft and corruption are not easy to resolve. Indeed, some informal income-generating activities are based on illicit operations, such as selling water or electricity by tapping into mains supplies. YEG interviewees described efforts to obtain official meters, permits or licences – to legalise their operations – as being expensive, bureaucratic and ultimately futile. So instead, they continue operating in the knowledge they are running on borrowed time until they are shut down.

Structural problems must be addressed

These findings should challenge policymakers to think about what micro-entrepreneurs really need to run sustainable businesses in informal settlements like Mathare. The YEG project shows that youth were enthusiastic in their use of the capital (and the phones) provided by the programme to start and grow businesses, but long-term stability, and growth, are reliant on a range of wider factors – particularly investment in public goods.

Reliable, affordable basic services, universal healthcare, secure property rights and security are all essential for micro-entrepreneurs to succeed but are hardly ever included as elements of urban livelihood programmes. Instead, there is a fixation on loans and business training, which will have limited impact unless underlying structural factors are re-oriented to support the needs of lower-income households and businesses. Unsurprisingly, the project found YEG participants less concerned about the role of their business skills in their success than the research team were.

Mathare’s micro-entrepreneurs have proved their capacity for survival in the face of so many continuous challenges, and the pandemic was simply seen as one more to tackle. While a significant shock like Covid-19 was an unexpected element oe YEG project, it has helped magnify the underlying factors that make or break the livelihoods of youth living in informal settlements.

————————————

[1] IEA, Informal Sector and Taxation in Kenya, 2012.

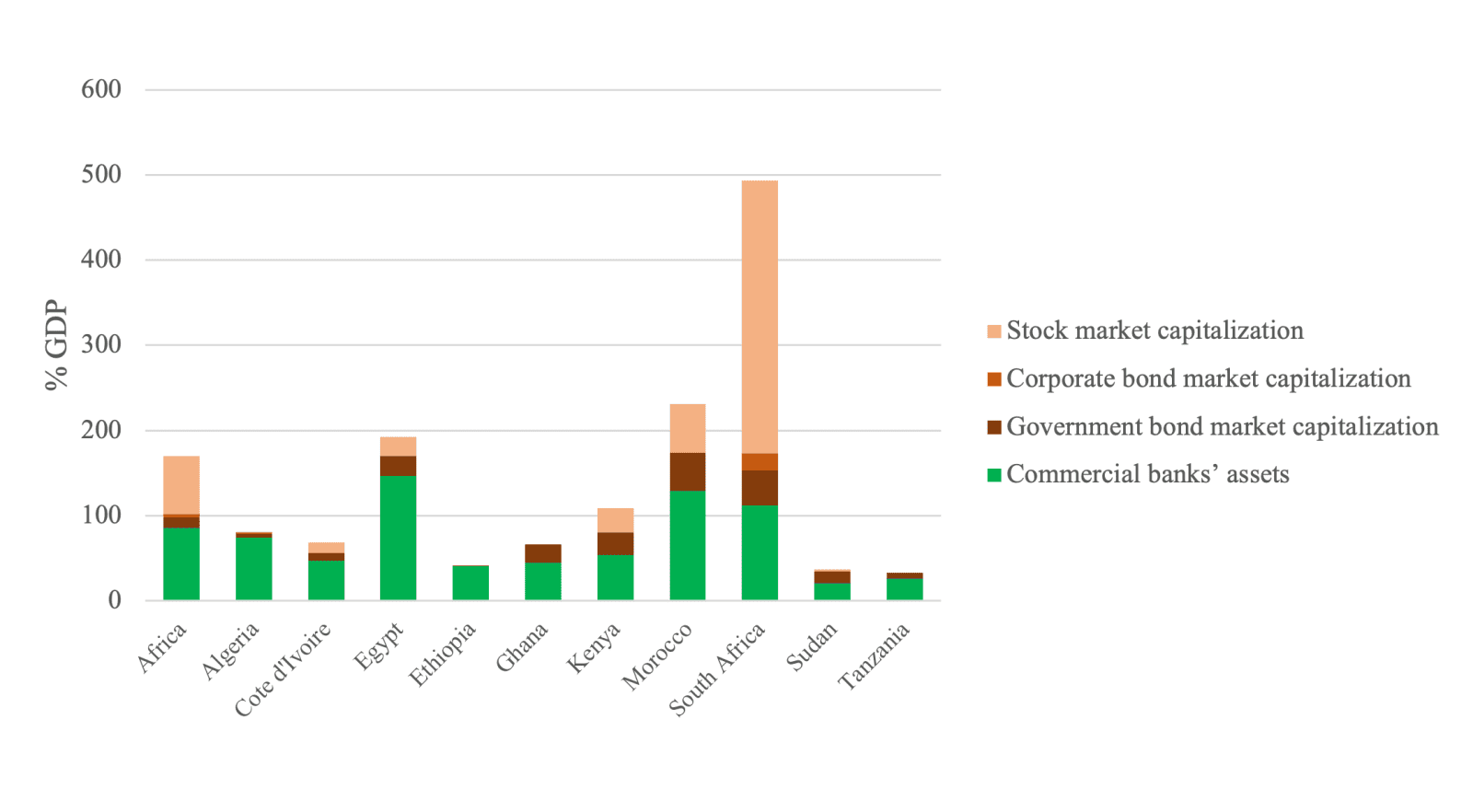

Sources: World Bank (World Development Indicators) and BIS, supplemented by the LTF Survey

Sources: World Bank (World Development Indicators) and BIS, supplemented by the LTF Survey