Long-term debt in Africa

Financial sector assets in Africa are heavily concentrated in banking, according to the latest research by the Africa Long-term Finance Initiative (LTF). Taken together, insurance company and pension fund assets represented less than 40% of GDP on average in 2019 across the continent, against an average of almost 100% of GDP for commercial banks. No surprises, then, that the largest providers of long-term debt in Africa are banks.

Why the lack of diversity in domestic sources of long-term debt? In part, it comes down to the risk aversion of fund trustees: most institutional investors in Africa prefer to invest in government securities and real estate rather than taking on project risks with which they are unfamiliar.

Instead of investing long-term saving commitments in long-term investments, institutional investors hold a significant portion of their assets as term and savings deposits with banks. This upends the maturity transformation role often viewed as the core purpose of financial intermediation – that is, meeting the needs of lenders and borrowers by taking short-term sources of finance and turning them into long-term borrowings.

Where institutional investors have been willing to take on project risk, their investment has been limited to brownfield infrastructure – projects that are already constructed with regular income streams from delivery of services, where the risks are much lower than in the greenfield construction phase. Even here, institutional investors typically lean on Development Finance Institutions (DFI)s to provide first loss-guarantees.

Turning to the role of commercial banks, a disproportionate share of bank lending is allocated to the public sector. The deepest segment of most capital markets in Africa is the market for government securities (mostly short-term): the volume of outstanding government bonds represents, on average, some 20% of GDP across the continent. By contrast, most African countries do not have a market for corporate bonds. Wher exists, the market represents less than 5% of GDP in most cases. This imbalance between deep sovereign debt markets and shallow corporate debt markets is exacerbated by the high concentration of liquidity in just a few capital centres south of the Sahara: Lagos, Nairobi, and Johannesburg.

Government securities are attractive to banks as they represent ‘risk-free’ assets and do not encumber banks in terms of capital adequacy. Conservative culture or ‘career risk’ also plays a role: as one bank executive in our network observed, “nobody worries about losing their job for buying yet more T-bills”. In some cases, as government spending ballooned in response to COVID-19, and credit risk associated with lending to the private sector increased, top-tier domestic banks have seen the purchase of government securities as a welcome “safe-haven”..

From the perspective of users of debt finance, although traditional banking products are available to most formal enterprises, they often come at a high costernative formal sources of finance only play a marginal role on the continent, access to long term finance is often constrained. Likewise, lending to the housing sector is very modest – the average percentage of adults with loans for home purchase across the continent was around 5% in 2017.

Not only are domestic markets for private debt constrained – we could say “crowded out” – by the borrowing needs of the public sector, foreign borrowing is also limited, and entails foreign exchange risk that increases its cost. This underscores the pressing need to deepen domestic debt markets for the private sector (both enterprises and households) across the continent.

The importance of long-term debt

Long-term debt is essential to sustainable development, in particular because it allows investments to be financed over their active lifetime, thus matching the liquidity needs of the investment project. Debt is also generally less costly than other forms of finance, such as equity, dueniority, its payment structure (regular installments) and (re)financing flexibility.

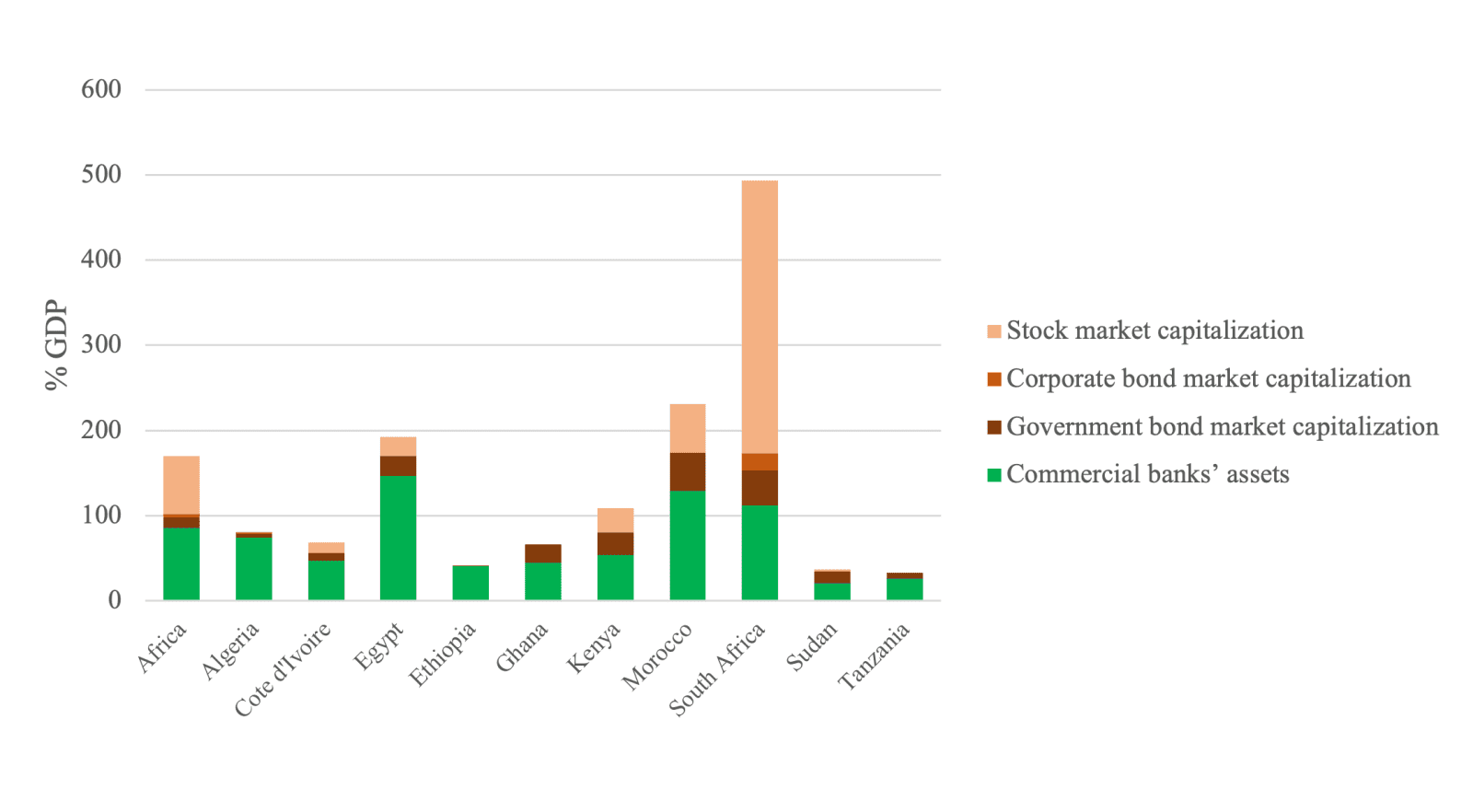

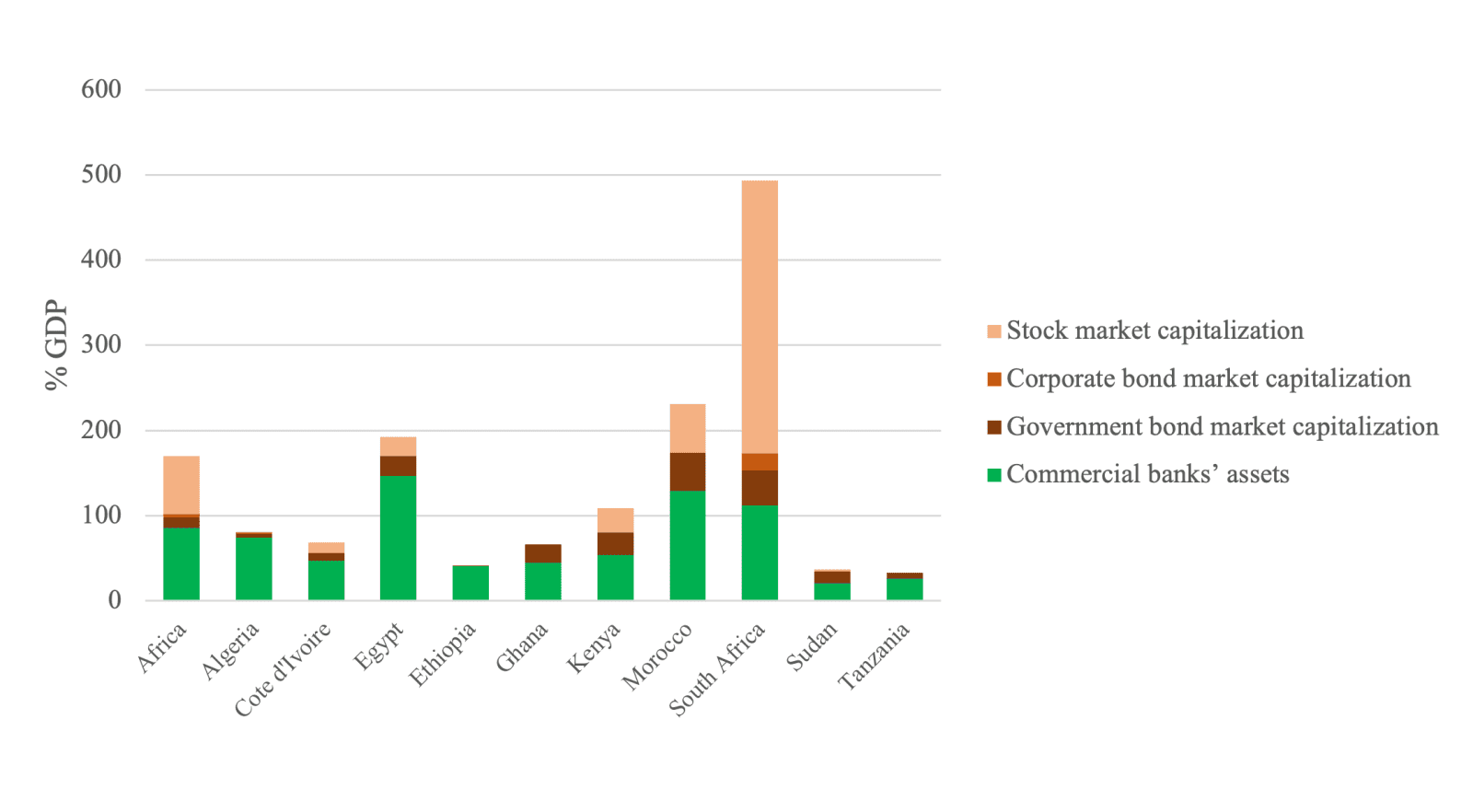

Depth of the financial system (2016[1], % of GDP)

The depth of the financial systems depicted in the figure below for a selection of African countries is gauged by commercial banks’ assets, government bond market capitalisation, corporate bond market capitalisation, and stock market capitalisation. The figure shows, for each indicator, the average across the continent in 2016 and the percentage for each country in the same year, scaled by GDP.

Sources: World Bank (World Development Indicators) and BIS, supplemented by the LTF Survey

Sources: World Bank (World Development Indicators) and BIS, supplemented by the LTF Survey

In developed economies, long-term debt finance is used by governments, enterprises, and households alike. For governments, debt is the only alternative to tax revenues when raising capital for investment. Enterprises find debt the most advantageous form of finance because it has a low cost of capital, often provides tax shields, plays a disciplinary role for managers and avoids diluting founders’ control. Households also find debt to be useful in alleviating liquidity constraints and thereby allowing them to smooth their income over the life cycle, opening up possibilities for purposes such as finance of housing, education and retirement.

Lack of data creates higher risk perception

In developed capital markets, the amount of long-term debt provided to the different sectors of the economy is well-balanced. Banks have a broad portfolio of loans that includes both public and privateending, and well-diversified institutional investors allocate their capital to both governments and corporates.

However, when data is not readily available to market participants, lenders tend to restrict their lending due to higher perceived risk. For example, solid and reliable credit history registries reduce these “information asymmetries”, allowing borrowers to have easier access to long-term finance.

By improving market intelligence through data collection, the LTF initiative seeks to deepen markets for long-term finance in Africa by reducing information asymmetries. Governments can use this data not only to benchmark but also to improve their debt management practices, enabling productive financing that yields return better than the cost of debt itself. Likewise, private sector stakeholders stand to benefit from being able to better manage the risks associated with their investment in local African capital markets.

Coordinated efforts need to be made by a range of stakeholders – private investors, public investors, concessionary lenders, and expert providers of technical assistance – to increase the deployment and investment of domestic sources of long-term finance in productive assets, especially those resources available for long-term investment by pension funds and patient capital investors. As we’ve outlined in this short blog post, the pis information asymmetry made worse by an inertia that comes from traditional over-reliance on government securities. For innovators, it is a status quo replete with opportunity.

Investment in productive assets like infrastructure will create a ripple effect on economic expansion over time. As economies expand, more capital for growth and scale-up is needed, which will attract larger foreign investment flows into Africa. This in turn will create job opportunities, higher disposable incomes and household savings, and – ultimately – inclusive economic growth.

[1] Data on government and corporate bonds are only available until 2016.

Sources: World Bank (World Development Indicators) and BIS, supplemented by the LTF Survey

Sources: World Bank (World Development Indicators) and BIS, supplemented by the LTF Survey