Recent years have seen large scale de-risking and financial exclusion happening in developing countries, particularly those countries that most need capital flows to finance social services, aid and development.

Where regional economic hubs are de-risked, it has a profound effect on the developmental outcomes for the hub itself as well as the spoke countries it is integrated with.

To stem the risk of illicit financial flows (IFFs), the threat of being de-risked and the corresponding knock-on effect on capital flows, it is important to ensure that there are adequate regulatory frameworks in place to promote a robust level of financial integrity in a way that does not undermine inclusion.

This two-note series explores the effect of de-risking and illicit financial flows on capital markets and the role of regional economic hubs to address financial integrity issues.

This note highlights the relationship between de-risking, illicit financial flows and capital flows in the context of regional economic hubs.

The next note, Identifying regional economic hubs in Africa, dives into the concept of a regional economic hub, exploring the methodologies for determining which countries are hubs within their respective regions.

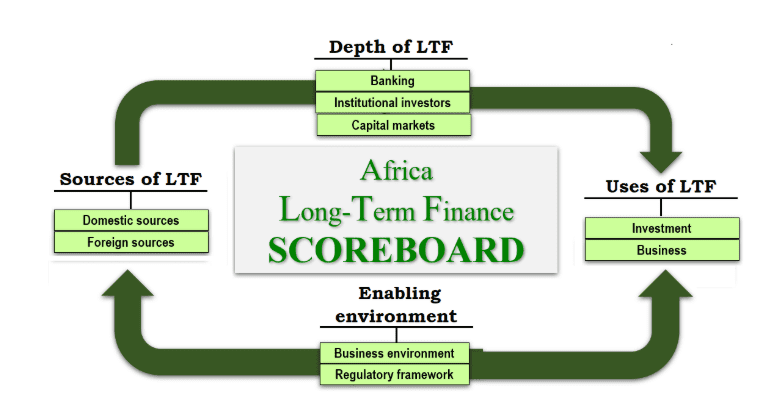

Capital flows, or moves between capital-rich and capital-poor countries depending on the opportunities for return on investment, and are important for economic development. These capital flows can consist of official capital flows, which include official development assistance and aid in the form of grants or loans, as well as private capital flows such as bank and trade-related lending, foreign direct investment, portfolio investments and workers’ remittances. Foreign direct investment (FDI), foreign aid and remittances are the major capital inflows in Africa. Such inflows play an important role in regional economic development. Between 2000 and 2017, FDI contributed an average of 3.4% to regional GDP in sub-Saharan Africa, with foreign aid and remittances contributing an average of 3.3% an2.3% respectively. These capital flows support job creation, skills and technology transfer, provide financing for government budgets and contribute to long-term economic growth. Capital flows are affected by the risk or perceived risk of illicit financial flows. Regional economic hubs can act as channels for IFFs, thereby in effect regionalising IFFs.

While Note 1 relies on the methodologies explored and utilised, Note 2, provides more details and specifics on the concept of economic hubs.

This work forms part of the Risk, Remittances and Integrity programme in partnership Cenfri.