Financial Sector Deepening programmes (FSDs) face increasing pressure to show that they provide value for money (VfM). This includes demonstrating that they are delivering their interventions efficiently and achieving their desired development impact. To achieve this, strengthening of internal procurement processes, as well as monitoring and results measurement (MRM) approaches, continue to be key areas of focus.

With these objectives in mind, FSD Africa commissioned the development of a new VfM approach, as a resource for the FSD Network – a group of FSD programmes including eight national programmes in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia and two regional programmes (FinMark Trust in Southern Africa, and FSD Africa).

The approach was developed by Oxford Policy Management (OPM) and Julian King & Associates, building on OPM’s approach to assessing VFM. This approach treats VfM as an evaluative question about how well resources are being used, and whether the resource use is justified. Addressing an evaluative question requires more than just indicators – it requires judgements to be made, supported by evidence and logical argument.

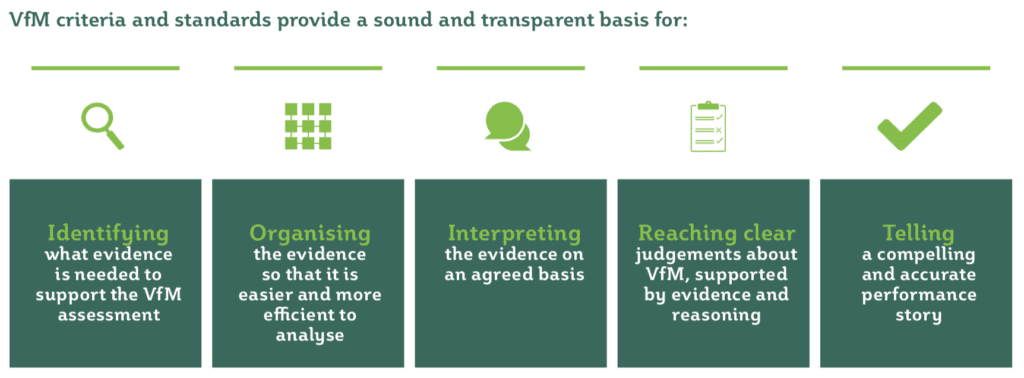

The VfM approach emphasises evaluative reasoning as a way to make robust judgements, transparently and on an agreed basis. It involves developing definitions of good performance and VfM, which are agreed in advance of the VfM assessment. The definitions include criteria (aspects of performance) and standards (levels of performance) developed specifically for the FSD context. Criteria and standards provide a systematic framework to ensure the VfM assessment is aligned with an FSD programme’s theory of change, collects and analyses the right evidence, draws sound conclusions, and tells a clear performance story.

FSD programmes are complex and their performance depends not just on quantitative indicators of delivery (such as number of projects completed) but also on the quality of implementation (e.g. sound adaptive management to respond to a changing environment and to act on emergent opportunities and learning). A mix of evidence is necessary to support well-informed, nuanced judgements about FSD performance and VfM.

Indicators play an important role in measuring some aspects of FSD performance. But restricting a VfM assessment to indicators alone would run the risk of missing important information about the quality of delivery and outcomes – for example, focusing on aspects of performance that are easy to measure at the expense of aspects that are important but difficult to quantify.

Therefore, the new VfM approach accommodates a mix of indicators and narrative evidence. The approach seeks to maximise use of rigorous evidence from existing MRM frameworks. It is aligned with the FSD Network’s MRM frameworncluding Impact-Oriented Measurement (IOM) Guidance (on how FSDs can better measure their contributions to changes in the financial markets they seek to influence), and the FSD Compendium of Indicators (setting out a common theory of change and related measurement framework that form the basis of common indicators to track FSD outcomes and impact).

The VfM approach is designed to support accountability as well as reflection, learning and performance improvement across the FSD network. It can also be used to systematically identify areas where MRM systems can be improved, to provide better evidence and benchmarking of sound resource management, delivery, outcomes and impacts.

The VfM approach is detailed in our new VfM Framework and Guide. The VfM Framework explains the conceptual design and rationale for the approach. The Guide sets out a practical, user-friendly, step-by-step approach for design, assessment and reporting on VfM. These documents will support a consistent approach to VfM assessment and reporting across the FSD Network, while retaining sufficient flexibility to reflect differences in context.

These frameworks have undergone rigorous development and testing over the past 18 months. As detailed within the documents, this has included a consultative process with FSDs and donor agencies, a staged approach to framework development with input from all FSDs, a full-day workshop with FSD MRM teams (at the FSD Conference in Livingstone, Zambia, November 2017), and piloting of the approach during 2018 with FSD Moçambique, FSD Uganda, Access to Finance Rwanda, and FSD Africa.

It is hoped that FSDs will use this comprehensive VfM assessment approach to support accountability, learning, improvement, and making investment decisions. The FSD MRM Working Group serves as an ideal community of practice to support effective and consistent application of the approach.