This article was originally published in the Africa Report on 23 November 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on the need for the African insurance sector to demonstrate its critical role in supporting people and businesses. The pandemic has been the most severe risk event in Africa in years, but many insurers have not delivered on their promise.

If the sector is to improve the narrative and rebuild trust, bold changes need to be made.

Over the past few months, we at FSD Africa have had discussions with over 80 insurers, reinsurers, regulatory authorities, associations and technical service providers across 27 countries in Africa to assess how the sector has been impacted by and is responding to the COVID-19 crisis. The broad consensus is that insurers have not fulfilled the role that the sector ought to play in responding to large systemic risk events.

Many businesses and households paid their premiums thinking they were covered for big risk events like the pandemic, but are now being forced to take general insurers to court to seek redress. In March, the Insurance Regulatory Authority in Kenya announced that all health-related COVID-19 claims would be honoured by insurers. Despite the initial agreement, as COVID-19 related health claims started trickling in, the industry began to backtrack on its commitmentJuly.

Some insurers are now turning away insured individuals who have medical bills worth thousands of shillings, saying that COVID-19 is a pandemic which is not covered by existing health policies. This is one of many examples where the insurance industry has struggled to deliver on its promises at time when it is needed most. As a result, trust is being eroded and many policyholders – whether it be businesses or individuals – are quickly becoming disillusioned with the sector.

However, there are some examples that do tell a more optimistic story. Companies like Prudential Life, which operates across eight African markets, added free new COVID-19 life insurance cover to existing and new clients and staff across their markets. Other companies including Hollard Mozambique and Naked Insurance in South Africa provided relief measures such as premium holidays and reductions to help take some of the financial burden off customers.

Rebuilding trust

In Africa, insurance is already anstry that individuals and businesses are wary of. Many often question its value: why pay money towards something that may not actually happen? Many are willing to take the gamble instead. Unfortunately, COVID-19 has, for the most part, exacerbated this perception, leaving the insurance industry at an all-time low.

With this low comes an opportunity for the insurance sector to step up and rebuild trust while adapting to new ways of doing business. Regulators have a key role to play. In instances where market consolidation is inevitable, regulators must act proactively to unwind weak insurers in an orderly fashion, ensuring that clients remain protected and their claims are honoured. If this transition is well-managed, there is potential to better facilitate market development and investment in products.

The insurance sector should prioritise innovation. The pandemic has highlighted the limited reach of insurance on the continent and the lack of products designed well enough to offer consums value and effectively address their risks and realities. Regulators should engage and support innovators as a key part of the recovery.

Meanwhile, insurers should encourage internal innovation and external collaboration with fintech to rethink and reimagine their approach to reaching new customers.

Now is the time for the insurance sector to reflect on how it can build trust in the sector by responding to customer realities and needs, and by meeting customers halfway. With largescale, systemic and society-wide risks like climate change continuing to gain prominence in the public conversation, insurers should use this time to enhance and accelerate efficiency.

The sector must consider resilience holistically and go beyond offering insurance products. Insurance alone will never be a sufficient mechanism to deal with major risks like pandemics or climate risks. We need to think about risk layering and public pools, consider options for risk prevention, management and mitigation by both pubic and private players. This applies at the macro and micro level. Micro and small businesses have been among the worst affected by the pandemic. They need tangible solutions that help them to understand, prevent and manage their risk – not just basic insurance policies that give poor cover for specific risks.

These are just recommendations. The choice to move forward is up to insurance companies. Do they continue with the old way of doing business or do they reinvent themselves to become more relevant to customer and business needs? What is clear is that insurers must adapt their business for the inevitable large-scale risks to come.

Recent years have seen large scale de-risking and financial exclusion happening in developing countries, particularly those countries that most need capital flows to finance social services, aid and development.

Where regional economic hubs are de-risked, it has a profound effect on the developmental outcomes for the hub itself as well as the spoke countries it is integrated with.

To stem the risk of illicit financial flows (IFFs), the threat of being de-risked and the corresponding knock-on effect on capital flows, it is important to ensure that there are adequate regulatory frameworks in place to promote a robust level of financial integrity in a way that does not undermine inclusion.

This two-note series explores the effect of de-risking and illicit financial flows on capital markets and the role of regional economic hubs to address financial integrity issues.

The previous note highlights the relationship between de-risking, illicit financial flows and capital flows in the context of regional economic hubs.

In this second note, Identifying regional economic hubs in Africa, dives into the concept of a regional economic hub, exploring the methodologies for determining which countries are hubs within their respective regions.

Despite the importance of hub economies, very little has been published on the identification and analysis of hub systems in sub-Saharan Africa. Regional economic hubs can be defined as countries that play a significant role in the economy of the broader region and have been found to help facilitate the movement of capital. They tend to have the most developed financial markets in the region as well as more favourable or developed regulatory environments. Hence, they act as gateways for capital to flow into the countries they are integrated with (i.e. their spoke countries). This interconnection between regional economic hubs and spokes can help create stable financial flows for countries in a region and contribute to the development of their financial systems.

This work forms part of the Risk, Remittances and Integrity programme in partnership Cenfri.

Recent years have seen large scale de-risking and financial exclusion happening in developing countries, particularly those countries that most need capital flows to finance social services, aid and development.

Where regional economic hubs are de-risked, it has a profound effect on the developmental outcomes for the hub itself as well as the spoke countries it is integrated with.

To stem the risk of illicit financial flows (IFFs), the threat of being de-risked and the corresponding knock-on effect on capital flows, it is important to ensure that there are adequate regulatory frameworks in place to promote a robust level of financial integrity in a way that does not undermine inclusion.

This two-note series explores the effect of de-risking and illicit financial flows on capital markets and the role of regional economic hubs to address financial integrity issues.

This note highlights the relationship between de-risking, illicit financial flows and capital flows in the context of regional economic hubs.

The next note, Identifying regional economic hubs in Africa, dives into the concept of a regional economic hub, exploring the methodologies for determining which countries are hubs within their respective regions.

Capital flows, or moves between capital-rich and capital-poor countries depending on the opportunities for return on investment, and are important for economic development. These capital flows can consist of official capital flows, which include official development assistance and aid in the form of grants or loans, as well as private capital flows such as bank and trade-related lending, foreign direct investment, portfolio investments and workers’ remittances. Foreign direct investment (FDI), foreign aid and remittances are the major capital inflows in Africa. Such inflows play an important role in regional economic development. Between 2000 and 2017, FDI contributed an average of 3.4% to regional GDP in sub-Saharan Africa, with foreign aid and remittances contributing an average of 3.3% an2.3% respectively. These capital flows support job creation, skills and technology transfer, provide financing for government budgets and contribute to long-term economic growth. Capital flows are affected by the risk or perceived risk of illicit financial flows. Regional economic hubs can act as channels for IFFs, thereby in effect regionalising IFFs.

While Note 1 relies on the methodologies explored and utilised, Note 2, provides more details and specifics on the concept of economic hubs.

This work forms part of the Risk, Remittances and Integrity programme in partnership Cenfri.

Digital platforms are virtual marketplaces that connect providers of goods and services with consumers. In 2018, the i2i facility identified 277 digital

platforms, of which around 80% were of African origin. These platforms derive revenues from facilitating interactions between providers and consumers of goods and services. Transactions are normally settled on the platform through various payment methods, such as bank cards, bank transfers, cash, mobile money and digital wallets.

A growing number of Africa-based digital platforms are starting to leverage their technology to channel financial services to their customers, therefore providing early demonstration of the ability of platforms to extend financial service reach to new or under-served individuals and small enterprises. They offer financial service providers access to customer data that enables more appropriate product design, as well as access to a range of payment solutions through which they can service these customers.

We are currently providing support to two innovative projects that leverage platform technology in collaboration with FSDs. This support s provided by Cenfri, through our Risk, Remittances and Integrity (RRI) programme.

Addressing risks and constraints in Kenya’s housing sector

We have forged a partnership with FSD Kenya and iBUILD, through Cenfri to understand and address constraints to providing construction-linked financial services in Kenya.

Kenya’s housing shortage is estimated to be around two million units, with over 60% of the country’s urban population reported to be living in slums. Only 7% of Kenyans are able to access formal housing finance, such as mortgage finance. Construction workers, building suppliers and other housing industry players face various risks, ranging from injury, loss of income and breach of contract, as well as constraints such as lack of capital and fluctuations in price or consumer demand.

iBUILD is a digital platform that offers the potential to contribute to tackling some of these issues and broadening financial service delivery to the sector. It connects construction workers with people looking to build and facilitates open access to housing support services that guide individuals through housing construction and reconstruction processes.

Cenfri has signed an MOU with FSD Kenya to rtake consumer research to help build a business case for insurance companies, banks, Microfinance Institutions (MFIs), Savings and Credit Cooperatives (SACCOs) and others to offer construction-linked financial products to users of the iBUILD app in Kenya.

The consumer research will focus on three iBUILD small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) users: construction workers, contractors and building suppliers. It will tease out the issues they face and identify how financial services could add value to their businesses, including asking the questions: How can finance add real value to small businesses and informal workers in construction? How does their participation in a digital platform help facilitate the delivery of innovative solutions?

The ultimate objective of this research is to support the launch of a financial service (insurance, credit or savings) that is distributed through iBUILD to its customers. FSD Kenya will engage with financial service providers to understand what such a financial produccould look like.

Building the resilience of e-hailing drivers in Rwanda

Through Cenfri, Access to Finance Rwanda (AFR) and Yego – an e-hailing taxi service in Rwanda – we are collaborating to help improve the resilience of e-hailing drivers by understanding the financial service needs of Yego’s drivers.

Yego is a digital platform that was launched in Rwanda in 2018. Like Uber, it connects passengers and local drivers of cars and motorbikes (moto) through a computer or mobile device. Yego currently has around 11,000 motorcycle and 2,000 taxi drivers signed up in Rwanda and is looking to expand on the continent.

Initial scoping suggests an encouraging opportunity to offer financial services, specifically insurance, to Yego drivers, who report that they trust Yego and would be open to procuring insurance through the company. Yego is keen on partnering with insurance firms to develop products suitable to the needs of the Yego drivers.

Cenfri has signed an MoU with AFR and Yego to support this collaboration. The objective will be to build a business case for financial service providers, specifically insurers, to service tharket through digital platforms. AFR and Cenfri will provide technical assistance to Yego in the form of consumer research and support to identifying an insurance partner, as well as during the product development process.

Many claim that Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), formally known as Digital Fiat Currency, can have many benefits for financial inclusion and has the potential to impact mobile money. But can CBDC overcome the challenges that current mobile money providers and consumers face?

First things first; what is “Central Bank Digital Currency”. Simply put, CBDC is a digital representation of physical cash. As its digital alternative, CBDC is interchangeable with physical cash on a one-to-one basis as valid legal tender, and adopts all three of cash’s key features: a unit of account; a store of value; and a universally accepted means of exchange between transacting parties. The distinction between CBDC and private cryptocurrencies are summarised below.

Figure 1. Digital Fiat Currency compared to Private Cryptocurrencies

Source: Cenfri, 2018

So, what’s the relevance of CBDC to financial inclusion?

CBDC has the potential to digitise the entire payments value chain, from the first to the last mile in a more cost-effective and efficient way. Cenfri’s 2018 report “The benefits and potential risks of digital fiat currencies” finds that CBDC, unlike cryptocurrencies, can promote adoption through network effects because of the key features that is shares with cash. CBDC’s speed, efficiency and safety (being backed by the Central Bank) introduces much needed trust in digital payment mechanism, something that is lacking in private cryptocurrencies and mobile money. And trust is critical where money is involved. Trust means that CBDC could eventually be adopted along the entire value chain (like cash) and hence could promote financial inclusion at all levels of society.

But what about mobile money specifically?

Mobile money may be a leader in “banking the unbanked” but the phenomenon still faces obstacles that undermine its uptake and use, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 2. Key supply and demand cost drivers of mobile money in SSA

Source: Cenfri 2019, based on data from various literature sources

The application of retail CBDC to mobile money can foster greaterinteroperability, improve payment efficiency, facilitate cost-saving gains and reduce key payment risks typically associated with mobile money. CBDC can also enable trust in mobile financial services due to its safety and the way in which its speed eases liquidity constraints of mobile-money agents. CBDC also eliminates the need for unnecessary third-party intermediaries and so streamlines payment clearance at the same time as enabling true interoperability.

How about the downsides of CBDC?

If CBDC is not implemented appropriately it could exacerbate contextual inequalities along the lines of digital, financial and economic disparities between population segments and also intensify the complexity of mobile money. For example, if not everyone has a mobile phone then only those that do can access CBDC; and if only certain areas have network coverage then only those in those areas can access CBDC; and so on. CBDC could threaten the intermediation role of traditional deposit-taking. CBDC could also exacerbate poor uptake of mobile money (e.g. due to illiteracy) simply because of CBDC’s (perceived) complexity. If everywhere you can only pay in CBDC then it may make the gap between illiterate and literate users even wider. The more vulnerable segments of the population, as primary unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) customers, could also be at greatest risk of identity fraud.

So what can be done to avoid these risks?

CBDC can bring maximum benefits to mobile money and financial inclusion if it meets certain pre-conditions. The basic principles to avoid these risks lie with governments and the enabling financial environment they create in their respective countries. Governments need to ensure appropriate and effective legislation and anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism regulation, as well as the implementation of robust consumer protection laws and national cyber-security defences. We know that that some developing economies lack these key laws – or lack the ability to uphold the legislation, even if it does exist. Through our Risk, Remittances and Integrity Programme, FSD Africa is partnering with Cenfri to combat these challenges by helping countries implement appropriate regulation that enables low-cost, efficient, domestic and cross-border payments to enable inclusive financial systems to operate at scale, and positively impact broader economic development.

It’s clear mobile money presents a significant use case for CBDC in the drive towards financial inclusion, but not without risks. If governments, supported by development partners, address these concerns, the impact of CBDC on mobile money could not only be positive, but could also contribute to significantly greater financial inclusion and better economic integration altogether.

You can delve deeper into the role of CBDC in delivering financial services to the unbanked and CBDC’s applicability to mobile money by downloading Cenfri’s latest report “Central Bank Digital Currency and its use cases for financial inclusion; a case for mobile money”.

Insurance has a strong role in combatting poverty and advancing development, in at least three ways:

Improving individual and household resilience

Insurance makes households more resilient in the face of financial shocks. Insurance also enables households to access services such as credit, health and education that may otherwise not be attainable to them.

Improving business resilience & productivity

Effective risk transfer is a fundamental part of corporate sustainability.

It also facilitates exports and imports, enables foreign investment and helps to ensure access – at better terms – to business financing.

Developing the demand and supply of capital

Insurance mobilizes capital through premium collection, its role in enabling business development and its linkages with the pensions market.It also pools capital into larger pots of funds that are more efficient to manage and invest.

Recognising the role that insurance can play in supporting sustainable development and growth, the UK’s DFID partnered with the World Bank, FSD Africa and Cenfri to conduct a series of diagnostics that explore how these three roles manifest in four countries in SSA: Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Rwanda.

This paper synthesises cross-cutting themes from the study countries and beyond and draws conclusions and recommendations on how to further develop insurance markets.

The World Bank (2017) estimates that the lives of 1.1 billion people who live without proof of identity could be improved by if they gain access to digital identity. Identity can help vulnerable people to gain access to critical services, such as health services, governments grants, education and financial services such as bank accounts. Lack of legal means of identification is a problem across SSA, with varying degrees of severity. In Nigeria, 78% of the population (149 million) do not have a legal means to prove their identity, while in South Africa 12 million individuals (22%) are excluded from the formal identity system of the country (World Bank, 2017). This translates to 454 million individuals (48% of the population) across the entire SSA.

Lack of identity is a barrier to accessing a multitude of important services, particularly financial services. In response to Anti- money-laundering initiatives spearheaded by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) (specifically Recommendation 10 on customer due diligence [CDD]), banks are required to have strong proof of identity of their customers in order to do business with them. This varies but generally includes identity documents and Proof of Address (PoA). Without such documents, consumers are excluded from accessing formal financial services. In Angola, 41% of individuals cited a lack of documents as the reason for being financially excluded, while in South Africa and Nigeria this figure was 14% and 12% respectively. Lack of identity documentation varies in its severity as a barrier to exclusion depending on the country, but overall indicates a significant problem (Findex, 2014).

Biometrics pose a possible solution to the identity problem in SSA and especially financial exclusion due to lack of identity.

In principle, insurers as institutional investors should also play a role in investment into the property market, either directly or by mobilising and catalysing capital markets.

Outside of direct property investments, however, there is a lack of feasible investment-ready opportunities in the sub-Saharan Africa property market.

From the findings, it is clear that the development community can promote the role of the insurance market in the property market (or other relevant economic sectors) by entrenching a holistic value chain lens in dialogues between the insurance sector, regulators and stakeholders from the real economy. This requires an understanding of the multifaceted ecosystem of the particular industry, including the actors in its value chain, and the incentives, risks and barriers faced by these actors at each segment of the value chain. There is also a need to (further) promote the development of investment vehicles that would allow efficient and aggregated investments into property markets at scale, and to rethink insurance products that meet the needs and limitations of property owners.

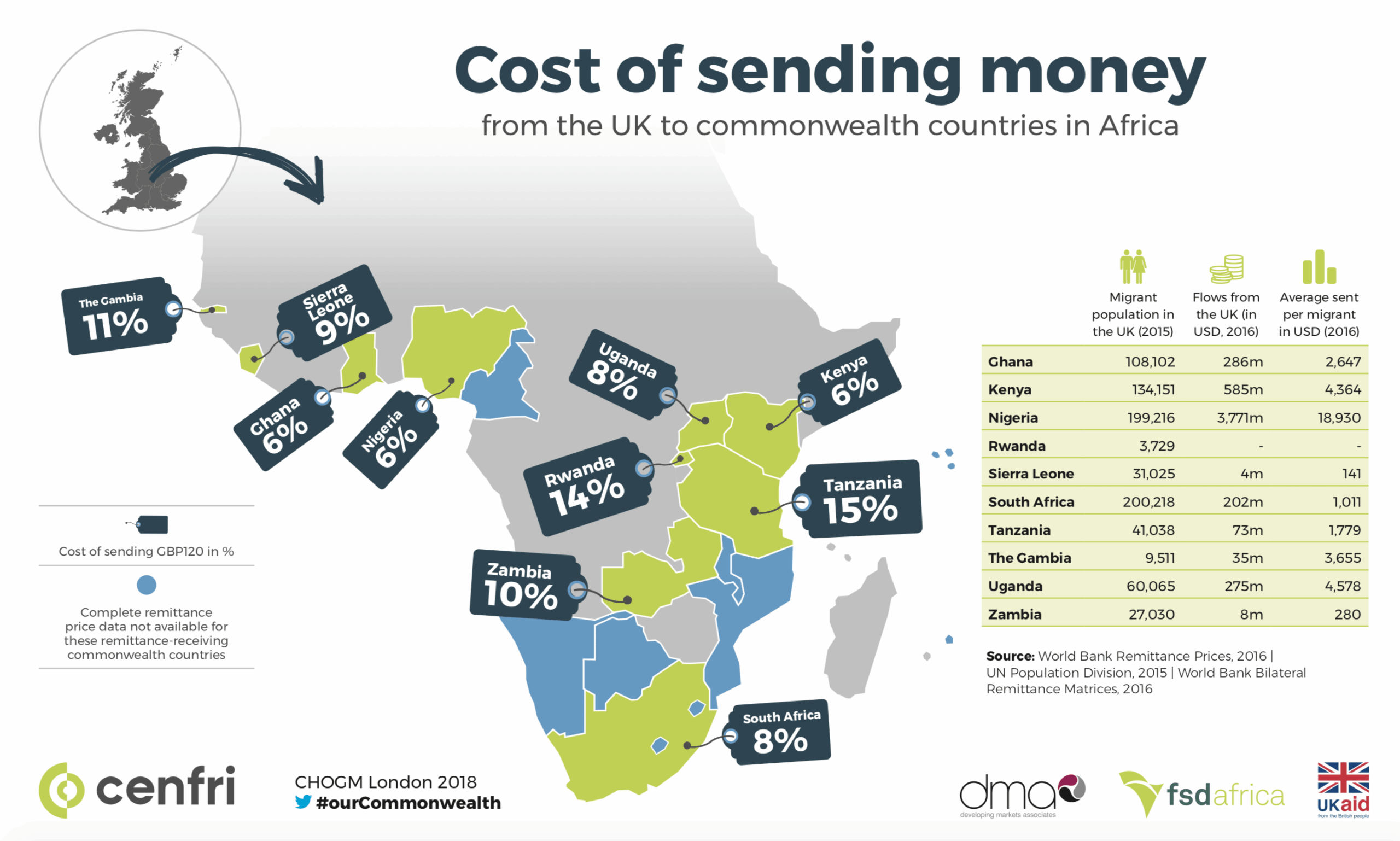

Remittance flows represent an increasingly important source of income for sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Between 2012 and 2015, formal flows steadily grew at a higher growth rate than foreign direct investment (FDI) and official development assistance (ODA). As a result, the value of formal remittances sent into SSA today almost matches those of FDI and ODA. Formal flows between countries in SSA are greater than ever. However, since 2016, the value of formal remittances sent into the region is no longer growing. Much of which is migrating to informal channels as SSA still has the most expensive corridors in the world, both in terms of sending funds from outside as well as within the region.

Remittances act as key sources of financial support for households: they reduce the likelihood of impoverishment, contribute to improved health and education, and provide greater resilience to financial shocks. To maximise formal remittance impact in the region, the true cost of sending and receiving the funds needs to drop to incentivise higher formal flows. This does not only include a decline in the remittances prices but also improved access for senders and recipients at the first and last mile.

To offer a more detailed analysis of the barriers to formal remittances in SSA, a new report from Cenfri and FSDA outlines the complexities of achieving sustainable cost reductions and increased access for remittance senders and recipients.

Vol. 1 of a seven-part series marks the start by identifying the most prominent corridors within and into SSA in terms of volume, cost and importance for the economy. It also investigates the relationship between remittance flows and migration patterns, used as a proxy to identify pain points in specific corridors. This report is aimed at remittance stakeholders, policymakers and anyone who is interested in understanding the remittance market in SSA in more detail.

Vol. 2 investigates barriers based on deep dives in four different countries in SSA providing the overarching barriers to understand a highly complex value chain. Vol. 3 – 6 provides case studies of the four countries against the backdrop of their unique country context. Vol. 7 concludes with recommendations on necessary policy actions and multi-country approaches for remittance players.

Vol. 3 explores the state of the remittance sector in Uganda and unpacks the key challenges and best practices within the industry.

Vol. 4 explores the state of the remittance sector in Ethiopia.

Vol. 5 explores the state of the remittance sector in Côte d’Ivoire.

Vol. 6 explores the state of the remittance sector in Nigeria.

Vol. 7 aims to provide stakeholders that are active in remittance sectors with recommendations on how to systematically overcome the supply-side barriers to formal remittances in SSA.